John Drabinski • September 27, 2016

It was a bit of luck and a lot of hard work, but my family and I managed to get tickets to the opening day of the National Museum of African American Culture and History on Saturday, September 24th. The museum is here forever, so the first day is just an especially festive day. And that it was. There were thousands of people gathered out front to witness the opening, in line to go inside according to timed entry, and inside across the five distinct floors of works reflecting on and presenting the African American experience.

That bit — the African American experience — is everything. My spouse and oldest son went to the opening ceremony while I watched it in my hotel with our youngest (conserving his energy, he’s only five). The ceremony had some great moments, from the funny yet profound trading of bits of African American poetry and prose between celebrities (Oprah Winfrey and Will Smith) to Patti Labelle singing “A Change Is Gonna Come” and doing Sam Cooke’s original proud (it was a moment for tears) to President Obama announcing the opening (whatever one thinks of his legacy, who could have imagined, ten years ago, that a Black president would close this ceremony) to the final ringing of a church bell from an historic African American church in Virginia by four generations of an African American family, the oldest — who held the bell’s rope tight — a child of a parent born into slavery.

All of that struck me about the moment. But I was especially struck by Obama’s opening motif, which described a block of stone in the museum that originally had a plaque affixed, stating that Henry Clay and Andrew Jackson has spoken while standing on this stone. The stone was a block used to buy and sell human bodies; it was, literally and figuratively, a foundation of the practice of enslavement. As Obama nicely put it, this is why the museum is necessary: it is necessary for the past to be told on African American terms, not on the terms of their tormentors. It’s worth quoting the words here:

What we can see of this building — the towering glass, the artistry of the metalwork — is surely a sight to behold. But beyond the majesty of the building, what makes this occasion so special is the larger story it contains. Below us, this building reaches down 70 feet, its roots spreading far wider and deeper than any tree on this Mall. And on its lowest level, after you walk past remnants of a slave ship, after you reflect on the immortal declaration that “all men are created equal,” you can see a block of stone. On top of this stone sits a historical marker, weathered by the ages. That marker reads: “General Andrew Jackson and Henry Clay spoke from this slave block…during the year 1830.”

I want you to think about this. Consider what this artifact tells us about history, about how it’s told, and about what can be cast aside. On a stone where day after day, for years, men and women were torn from their spouse or their child, shackled and bound, and bought and sold, and bid like cattle; on a stone worn down by the tragedy of over a thousand bare feet -- for a long time, the only thing we considered important, the singular thing we once chose to commemorate as “history” with a plaque were the unmemorable speeches of two powerful men.

I’m not sure who wrote Obama’s speech for this occasion, but this is a great bit of writing and an observation — one that is familiar to any and all students of Black Studies — that radically shifts our perspective on the foundational meaning of our world. A block of stone. A foundation of sorts. A foundation on which one story, the one coded on the plaque, is told, and we know how that story is a window into bigger and bigger versions of that same moment. But it is also the foundation on which another story has already been told, one told but not heard loudly enough: the story of African American suffering, resilience, resistance, subversion, excellence, survival, thriving, beauty, world-making, world-changing, and, in the end, the creation of a people. In that series of words, we see what we call African Americanness — a story told in culture and history, yet muted because it is too often the story of Clay and Jackson standing on a foundation worn down by the tragedy of over a thousand bare feet. The museum unmutes that and pries off the plaque, so to speak. Then it finds the voices and names and stories (plural, there is no singular and the museum makes sure we know that) that make up the “African American” in the museum name African American History and Culture. Therein lies the aspiration and aim.

So the question is put for everyone visiting: does this tell the past and the present from an African American perspective? Does it do it well? And is it comprehensive?

Scholars and thoughtful, readerly people will debate that. Anyone who has a particular interest or passion will likely be critical — it is a finite space, and what one learns quickly, if one did not already know, is that the African American experience is so vast and complex that no museum can give every detail adequate treatment (nor should it pretend to). There is the question of comprehensiveness. No museum can pass that test. There is also the question of telling a story with depth, with aggressive and interesting pedagogy, and with coherence across historical period. This is a multi-century story. It’s a big task to tell it.

The museum itself is beautifully put together. The outside doesn’t photograph well, if you ask me, because I’d seen the photos and thought it looked a little industrial. But when you’re there, in person, it is just stunning. Seen from the outside, the exterior draws your eye in close to detail; when you’re inside, it is full of light and feels vast, open. The museum really photographs well at night. Stunning, really. Walking up and into the museum, I’ve honestly never seen such an excited, intense crowd in my life. That’s the honor, privilege, and pleasure of going on the first day — though I’d bet it will feel like that for many, many days or even weeks and months. Everyone was buzzing and smiling and talking about their excitement on the way in, then quiet, thoughtful, readerly, ecstatic, sad, dumbfounded, speechless, and all those emotions that come with surveying an experience that moves from the trauma of the Middle Passage all the way up to thrills and victories of Olympic athletes, world-changing musicians, poets reading, Nobel Prizes being awarded. And everything in between.

We started at the top floor rather than the logical (and probably expected) start from the basement, which is to say, we started with an astonishing monument to black excellence, beauty, and achievement, which is simultaneously a story about refusal, resistance, and subversion. The museum does a wonderful job of blending that at every turn; there is no misery and abjection

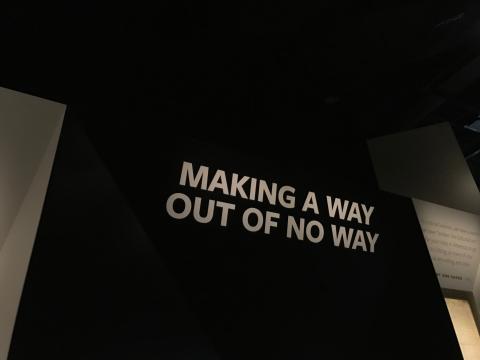

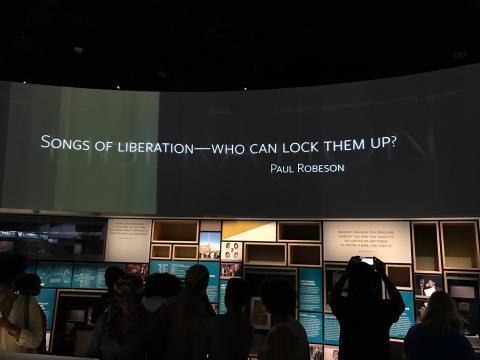

left to itself, but there is instead always an intertwining of suffering with subversion, survival with world-making, abjection with creation, excellence with resistance, and beauty as a conscious overcoming of, well, everything. Therein, African Americans become subjects in history, not merely objects. Actors who made a world out of fragments, not objects who were acted upon. Again, history from the African American perspective — one that takes actual African Americans seriously. Making a way out of no way.

The top floor talks everything from culinary traditions to gestures and speech to music, poetry, and literature. And it does it with the best media, full of sound, color, faces, history…overwhelming in the best sense. And then the floor just below, which will probably be the most photographed: a history of sports as racial discourse, protest, excellence, celebration, and all of that rolled into one. As you’d expect, Jackie Robinson and Muhammad Ali stand out, as do Tommie Smith and John Carlos in a stunning sculpture of their 1968 raised fists on the medal stand. You can’t leave this section without smiles and a sense of so many things being possible. You also can’t leave with the impression that sports is just competition and entertainment. Sports is and always has been politics and a place where Black people have resisted and refused, for sure, but also a place where African American excellence has been on the world stage saying, in the midst of so much awfulness, “we are here and we are great.” Clips of Jesse Owens at the Olympics in Germany capture that perfectly, as do Smith and Carlos raising a black-gloved fist while being crowned the fastest humans on earth. There was a giddy, loud line of people waiting to be photographed with the Serena and Venus Williams piece. Rightly so!

From there, we went to the natural starting point, the very bottom floor. That floor begins where the whole African American journey begins: the Middle Passage. Whereas the top two floors were open and airy and exciting, the bottom floor is crowded, small, and stifling by comparison. You weave shoulder-to-shoulder with other museum goers. No one talked much. Some people muttered about how it was too much. And it is too much. It tells the story in no compromised terms about the trade in enslaved persons, underscoring in one important panel how no aspect of human life was untouched by this terrifying, all-encompassing trade. Sugar in tea, wealth among elites, banking and insurance systems, foodways and folkways - these were all inseparable from enslavement. We don’t live free of those traces today. The most ghostly moment, for me, is a darkened section with text and fragments of a slave ship. Traces, fragments, recovered from the ocean’s floor. It recalled for me Derek Walcott’s stunning poem “The Sea is History,” which evokes the ocean floor as an archaeology of blackness and the Black experience. There is a bit of that brought to the surface in these fragments in the belly of the museum. It is humbling and full of silence, yet very loud.

The story of slavery follows from that. The museum’s story of enslavement, in my view, is pretty comprehensive. It is also like most of the museum: it uses very few words and leaves you to sit with the experience of those few words. What an interesting aesthetic. That means the words have to be perfectly crafted, for they have only that short moment of reading to convey an entire world. The words are excellent, the writing perfect. It’s like the best pedagogy brought to a museum, a multii-floored classroom in which the teacher evokes and explains just enough, then sets you free to settle into the experience of this terrifying point of origin.

The bottom-most floor tilts up slightly into what will surely be the most discussed part of the museum. You exit the claustrophobic space that has introduced you to the crushing centuries of enslavement and the ceiling is suddenly high, you see the familiar declaration of freedom and independence, the nation’s articulation of itself as a radically free place - all men are created equal. Large statues and words take up two floors of wall. And from there you turn right and continue the story of slavery, read about the underground railroad (the bit telling Harriet Tubman’s story is wrenching and amazing), then slowly the Civil War, emancipation, Jim Crow, the Civil Rights Movement, and up to present struggles to confront racism, racial oppression, violence, and exploitation, as well as exploration of the new languages we need to see the transmission of the grotesqueness of our history into the present (I’m thinking here of a large video screen featuring a discussion of “white privilege,” a new twist in our attempts to find words for racism and racist practices and habits).

What to make of this transition from slavery to the Declaration of Independence, which is really not one? It’s a deeply effecting, incredibly cruel irony that takes me back to that opening bit from Obama: the African American experience needs to be told, precisely at that moment. My 13 year-old put is perfectly when I asked him what he thought of that turn on the museum floor: “It made me so angry that I wanted to punch something.” Indeed. That’s the cruel in “cruel irony.”

I am also sure that the civil rights era and after will earn a lot of debate and discussion. This is really such a well-documented part of U.S. history and there are so, so many stories to be told. I liked the way the museum dealt with it, personally, and I very much look forward to how scholars and others critically assess it. Martin Luther King, Jr. is of course a major figure in all of it, as he should be, but the museum makes a great choice in not binding the era entirely to him — something popular histories and our memories tend to do, almost without exception. The museum chose a scattering effect instead, throwing out bits and pieces about various figures in the mainstream movements, Black Power and Black Panther movements, and includes a huge iPad-like table in which you (and a dozen-plus other people) can grab and explore various images from around the country, including all the familiar centerpieces of African American history (Harlem, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Birmingham, New Orleans, Memphis, Atlanta, etc.), as well as many of those we might not think about on first thought (the southwest, West coast, midwest plains, etc.). The choice of plurality is important and exciting in this part of the museum. The walls also explore the African American military experience in some detail (something our department’s own Professor Khary Polk has made central to our accounting of Black history in the department).

You leave these rooms, every phase of the museum, with a lot to think about, provoked to read and explore beyond the museum walls. I’m a professor. That’s a win in my book.

We spent over three hours in the museum. It was not nearly enough. More visits are necessary. It was so interesting, though, for us to have reversed order, to have begun with the monument to beauty and excellence, then moved to traumatic origins. If you start from the proper beginning, on the bottom-most floor, you really do get the existential experience — through text and image, but also through the management of bodies in space as you walk - of this, the museum’s central understanding of African American experience: if you make it through this impossibly terrifying place, you find beauty and excellence. But we had it backwards: you see this beauty and excellence, let us not forget whence it came, what had to be survived, resisted, and overcome, let us witness with awe and love the just flat out refusal to let being given nothing result in becoming nothing. Again, that central idea of the museum, that there is no misery without world making, no violence without subversion, no excellence without resistance. Nothing is redeemed. Just a complex, astonishing story that is central to the place we live, the ground we stand on, and now has a documentation unlike any other. As that panel put it, and it was the one I kept seeing everywhere, encoded in so many installations: Making a way out of no way.

Obama made this other remark that really stuck with me, partly for its words, partly for his hesitation in saying it - his voice got caught with emotion and paused. “We're not a burden on America, or a stain on America, or an object of pity or charity for America.” To have made a world when it was impossible to do so, when all of the world’s resources were dedicated to making it impossible to live and breathe and create, yet exactly that was done - that is the museum in a flash. The details are lovely. The experience is total. It’s worth your time and travel. Make your way over.