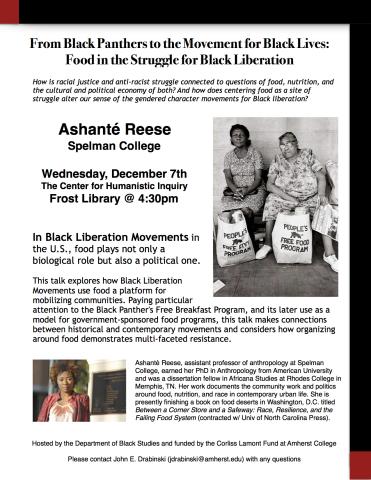

Ashanté Reese • September 27, 2016

Ashanté Reese teaches in the Department of Anthropology and Sociology at Spelman College. She is guest blogging here in anticipation of her public talk on Wednesday, December 7th at 4:30pm at the Center for Humanistic Inquiry (Frost Library, Amherst College), in which she will discuss the relationship between food, gender, and race in Black liberation struggles. The talk is entitled "From Black Panthers to the Movement for Black Lives: Food in the Struggle for Black Liberation." A poster for her talk is at the end of this reflection.

When I decided to become an anthropologist, I realized why it was on the "Stuff White People Like" blog. Most of my friends and family from my largely black, rural, working class background had no idea what anthropology was or what it meant to say you are an anthropologist.

(See this interesting interview with Karen Brodkin, a well-known anthropologist, in which she refers to anthropology as "white public space.")

I would tell people I am an anthropologist (or anthropologist-in-training while in graduate school) and I would get some variation of, oh that's nice...so what is it that you do with anthropology? Go on digs and stuff?

Well, no. I don't go on digs, but I do a lot of digging in my work.

My first job out of college was teaching middle school. The students I taught were the first to inspire me to think critically about the social, political, cultural dimensions of food. Coming from a rural background, my 22-year-old self was pretty naive about city-based inequities in food access. One day I took two of my middle schoolers to get physical exams so they would be eligible to join the track team. Afterwards, we stopped at the grocery store in my neighborhood to grab a few things for dinner. My ordinarily rowdy, needing to be corralled students were quiet and afraid to touch anything. When we sat down to eat dinner at my house, one of them mentioned how nice and "white" my grocery store was and that they had nothing of the sort near them. I asked what did they have, and not one of the things they named was a grocery store. Those students lived 3.3 miles from me.

Their questions became my questions. Broadly, my research concerns understanding the development and effects of our contemporary food system in predominantly black communities. I examine the ways that food inequalities are not simply products of "choice" or lack thereof. Instead, the food system is embedded in and reflective of how racism consistently influences or shapes access to resources, including the unequal distribution of food. I am most interested in how to reframe our thinking from considering these inequalities as byproducts of a broken food system to considering them as embedded inthe food system. Ethnographically, I am most interested in how people experience and resist these inequalities.

I don't physically dig, but in my work I spend much of my time digging beneath the layers of policies and everyday practices to understand processes and mechanisms. I listen to people's stories about food in their childhood, routes to the grocery store, gardening, and their perceptions of their communities. I participate in planting seasons and community-led efforts to mobilize around increasing food access. I hang out with small business owners who I now consider friends. I geek out in archives, as I am particularly interested in how and when narratives around violence, race, and food develop and change over time.

So, now when people ask me what do I do, I usually say two things: I follow the stories and I study food. That seems simplistic, but at its core, that is the essence of my work. I listen, I look, and I learn from whatever and whoever is talking. Neighborhoods and people speak all the time. I get the great fortune of recording and analyzing what I hear.