Mary Hicks • December 8, 2016

Frederick Douglass and Us: Teaching Black Atlantic History in the 21st Century

In a composite nation like ours, as before the law, there should be no rich, no poor, no high, no low, no white, no black, but common country, common citizenship, equal rights and a common destiny.

- Frederick Douglass

Twenty years ago, on the cold and snowy mornings that characterize Iowa winters, my father James Hicks would drive me and my brother to school. In an age before smart phones and tablets, I would silently sit in the back seat imagining what the day would hold and staring aimlessly out the window. My father, on the other hand, loved to start the day off either with NPR blaring or by popping his favorite cassette into the car stereo.

I was quite aware then that unlike most dads, my father’s favorite tape was a compilation of Martin Luther King Jr.’s most well known speeches. Frequently, my dad would turn up the volume at what he noted were particularly poignant moments, exhorting to his children to pay attention, and to let the words sink in. Sometimes he would repeat King’s language for effect, pointing at the speakers. His favorite speech was King’s final one, made on April 3, 1968 to an audience of striking sanitation workers in Memphis on the eve of his assassination.

Like all of King’s speeches it was marked by a profound expression of universal humanity, as well as the kind of soaring oratory that most of us can only dream of realizing. The speech notably left its working-class Black audience in tears and aroused a renewed sense of urgency for their long struggle to receive a living wage. Most prophetically, King also drew attention to his own mortality and candidly confronted his own emotional battle to carry on his social justice activism in the face of growing threats to his own life. The crux of the speech delivered with a simultaneous sense of hope and bittersweet recognition that had become for my father a kind of prediction of his untimely passing. King remarked:

Well, I don't know what will happen now. We've got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn't matter with me now, because I've been to the mountaintop. And I don't mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life — longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over, and I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. So I'm happy, tonight. I'm not worried about anything, I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.

King, like many humanists, conceptualized history through a teleology of progress—believing a better world was still ahead. But unlike most, he rejected the notion that such progress was inevitable, instead believing that it was only through the collective and protracted campaigns of morally informed action that true equality would ever be realized. Rejecting notions of speech as politics, and ideals as action, he argued that all Americans—both white and black—were required do much more than declare our values, instead he maintained that it was imperative that we live them.

Though I didn’t recognize this at the time, for my dad, King’s message also embraced the necessity to work for a brighter future for all, even if you personally would not be around to enjoy the fruits of the struggle. History and its arc are larger than any one individual person. I was too young at the time to understand the significance of the intellectual and political heritage that my father wanted me to absorb and live by. But now as a scholar of the Black Atlantic, I recognize that the essence of King’s “Mountaintop” speech in many ways reflected a longer black intellectual tradition, dating back to the days of slavery. His words evoked a simultaneous trenchant critique of Western values and attendant hypocrisy, as well as an abiding faith in the ability of African Americans to transcend these obstacles through direct action. As one of the professors who trained me was fond of saying of this inherently optimistic gospel impulse, “Black people are always the first ones to say, ‘freedom is always just around the corner.’” Progress, it seems, has always been understood to be our collective destiny as a people.

The recent opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington D.C. caused me to think back fondly on those mornings, and attempt to reimagine what I once perceived to be parental eccentricity. I remembered an earlier conversation I had had with him when he noted in passing that the Smithsonian had purchased one of the artifacts in his collection of Black memorabilia. Though my father was never trained as an academic, he developed a passion for collecting relics of African American life. First, he began accumulating early 20th century toys, pictures, and advertisements that featured racist imagery, and then later expanded his collection to acquire items produced by African Americans themselves— including books and artwork. Due to this passion for material history, my childhood home was stuffed with shelves upon shelves of antique books, while the walls were covered with a diverse set of images ranging from photographs of minstrels to drawings of Abraham Lincoln, and portraits of Paul Laurence Dunbar and my great-grandfather sporting a three-piece suit while mounting a horse on his Mississippi farm at the turn of the 20th century. In Iowa, my father had become a major regional figure in the world of Black memorabilia, exhibiting his collection in Presidential libraries throughout the country, all despite the fact that collecting was only a hobby for him, not an occupation.

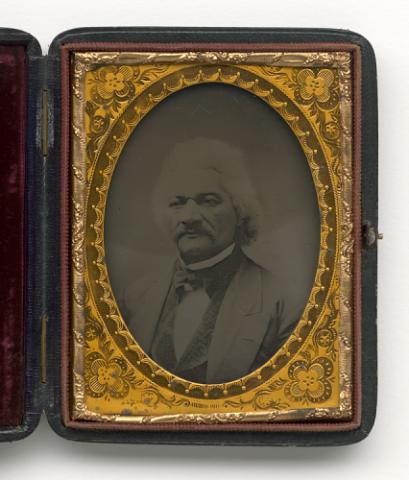

I remembered too my father’s prized artifact, a tiny black and white image of anti-slavery activist and critic of American democracy, Frederick Douglass, no bigger than the palm of my adolescent hand and enclosed in a delicate leather case lined with rich red velvet. Frederick Douglass looked stern, staring out at the glass images’ observer with intense eyes. My dad had shown it to me once around the same time we were listening to King’s oratory on car rides to school.

With my interest piqued, I did a quick online search of the National Museum’s holdings and to my surprise an image of the ambrotype I remembered from middle school appeared before my eyes:

I quickly called my father and revealed the news, to which he responded approvingly, “We made it to the Mall on Washington,” perhaps unknowingly echoing King’s legacy of imagining of black progress in terms of the claiming of symbolic space within the figurative heart of the American nation.

The ambrotype, featuring an apparently older Douglass capped with white hair, my father informed me, had likely been taken by a photographer in Albion, Iowa, a rumored site of the Underground Railroad for enslaved people escaping from the slave states of the South to the relative freedom of the North. A friend and colleague at Smith College who specializes in the history of photography noted that ambrotyping, as a form of glass plate photography, cannot be reproduced. This meant that the image was original, and Douglass himself had sat in the room with the photographer who had taken it.

My dad had acquired the piece from an elderly woman living in the historic home of a local photographer who had passed before the dawn of the 20th century. A previous owner had left Douglass’ ambrotype in the home’s attic. Because my father was a locally known collector, the woman who had discovered the ambrotype contacted him and offered to sell it. He was likely one of the first to see the image after a period of neglect lasting over one hundred years. Quickly arranging the funds to purchase the antique, it ultimately became the crown jewel in his collection.

Continuing this unlikely trajectory, a long forgotten attic curiosity now sits in a National Museum that has already attracted thousands of visitors from around the world. Every one of the museum’s visitors I have spoken to have found the experience of walking through the exhibits profoundly moving and enlightening, as it brings together rare material artifacts—or the fragmentary remnants of history—and cutting edge scholarship to tell the long and moving story African American life. Like my father had tried to impart to me years earlier, the National Museum and its visitors recognize the vital importance of history as a lens onto the black experience. History explains not only the persistent the legacies of oppression, discrimination and exclusion that have characterized the American past and present, but also a vibrant African American heritage of ingenuity, creativity, heretical thought and dissident action.

A former slave, Douglass—the most photographed American in the 19th century—was emblematic of both strands of this history. Though he had once been human property, a mere body to be economically exploited, he was also a political visionary, an accomplished orator and author, and an activist. He was in short, like all enslaved historical subjects, a three dimensional human being, not merely a body, but a person of sensitivity and intellectual complexity. Furthermore, Douglass profoundly shaped the path of American democracy by articulating critiques of national hypocrisy and injustice. Through the deployment of plainspoken metaphor, he laid bare the contradictions of American life. In one famous speech he rhetorically intoned, “What, to the American slave, is your Fourth of July?”

Beginning in the 1840s, Douglass began advancing a kind of radical egalitarianism that was unimaginable for most white intellectuals and activists of the time, even those who opposed racial slavery. The painful experiences Douglass suffered under yoke of enslavement forged Douglass’ unique worldview and a radical philosophy of history and politics; he often proclaimed that as a former slave, he understood with greater precision the meaning of freedom than any white man ever could.

As a stalwart advocate of both education and activism he believed the challenge of eradicating slavery and realizing racial equality required both black intellect and direct action in equal measure. Rigorous thought and practical organizing had to be combined. Like King a century later, he consistently expressed everlasting faith in renewal for African-Americans and the nation, even after the most devastating of setbacks such as the Dred Scott Supreme Court decision of 1857 which precluded blacks from becoming citizens of the United States. Like King, he continually worked to fashion “hope out of despair” in the words of the historian, and former Amherst College Black Studies Professor, David Blight. Drawing inspiration from scripture, he proclaimed after the Scott decision, “I walk by faith not by sight.” His vision of a brighter future led him to engage in a radical politics that had no precedent or guarantee of success. He was driven after the many disappointments wrought by the end of Reconstruction to always look for the possibilities, the openings that would allow for the completion of the project of full racial emancipation.

Like King, his optimism for human progress was tempered by the bitterness of betrayal and defeat. He earnestly believed, however, in the power of black collective action. Incrementalism, he trusted, would ultimately win the day. His words of advice to fellow idealists still resonate with us today:

Let me give you a word of the philosophy of reform. The whole history of the progress of human liberty shows that all concessions yet made to her august claims, have been born of earnest struggle. The conflict has been exciting, agitating, all-absorbing, and for the time being, putting all other tumults to silence. It must do this or it does nothing. If there is no struggle there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom and yet depreciate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground, they want rain without thunder and lightening. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.

He continued:

This struggle may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, and it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will. Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them, and these will continue till they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both. The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress. In the light of these ideas, Negroes will be hunted at the North, and held and flogged at the South so long as they submit to those devilish outrages, and make no resistance, either moral or physical. Men may not get all they pay for in this world; but they must certainly pay for all they get. If we ever get free from the oppressions and wrongs heaped upon us, we must pay for their removal. We must do this by labor, by suffering, by sacrifice, and if needs be, by our lives and the lives of others.

For Douglass, unlike many white liberals of his day, progress was never assured. Nor was universal human enlightenment. Progress, equality, the recognition of a universal humanity were merely ideals, it was the responsibility of people to assure their triumph. This conceptualization of history, that the world is what we make it, was strikingly modern for the time. Douglass, like contemporary historians, placed his faith for the course of history in the hands of people, not ideas or divine provenance. He saw neither injustice nor progress as inevitable or immutable. What was achieved could be reversed, what was taken away could be regained through struggle—both moral and physical. Neither success nor failure was ever absolute or final. This observation was drawn from the ebbs and flows of history he witnessed over the course of his own lifetime: emancipation, the hope and later unfulfilled promises of Reconstruction, and the beginnings of Jim Crow segregation.

Revisiting this family memory has allowed me to rekindle my own commitment to teaching and researching black history. Like my father, I was first drawn to history because of the opportunities it presents for realizing radical empathy—or the intellectual praxis of viewing the world through the eyes of people drastically different from ourselves. In my courses Introduction to the Black Atlantic and Age of Emancipation I emphasize the evolution of black thought on the very same complex issues, which confront people the world over today. Enslaved people and their descendants throughout the Atlantic existed on the vanguard of the profound transformations of the modern world. They were among the first theorists of democracy, notions of national belonging and human rights, and their ideas irrevocably shaped the course of world history. As we study the words of Douglass today—piecing together the fragments of history in the classroom and beyond—we can take inspiration from his prophetic democratic vision.

- Prof. Mary Hicks