Contents:

- The Early Years

- The Garman Years

- The Newlin Years

- Alexander Meiklejohn

- The Post-Meiklejohn Era

- The Post-World War II Era

- Expansion

Image

The Early Years

From the founding of the College until around 1880, philosophy had been taught in the same way at Amherst. The President of the College would teach a required philosophy course to Amherst students in their Senior year. President Julius Hawley Seelye was the last president to teach the course and like many philosophy courses in America at the time, it involved material in what might broadly be called logic and epistemology, ethics, and the history of philosophy.

Seelye was a graduate of the class of 1849 and studied philosophy at Halle, Germany in 1852-53. He was made Professor of Mental and Moral Philosophy in 1858 and held that position until his retirement in 1890.

In his teaching, Seelye used Laurens P. Hickok's A System of Moral Science (1853) and his Empirical Psychology; or, The Human Mind as Given in Consciousness (1854); Seelye even contributed to the revision and editing of these works. Another text at Amherst was Albert Schwegler's History of Philosophy (1867), of which Seelye also made a translation.

The Garman Years

In the academic year 1880-81, an elective in philosophy, "Rational Psychology," was offered to Amherst

Garman produced over the years a series of pamphlets for his students on philosophers and philosophical topics. By 1907, there were nearly one hundred of these. Very few knew their content, for Garman permitted them to be read-only by his students. (One is reminded of Harry Sheffer at Harvard.) Even President Merrill E. Gates was denied permission to see them in the early 1890s.

Garman's teaching was considered subversive by some for he encouraged his students not to memorize or parrot what they had heard, but to think through the issues for themselves and come to their own conclusions. Inevitably, however, Garman emphasized a religious perspective on the world and values. That said, he incorporated a considerable amount of psychology into his courses (many philosophy departments in the U.S. began life as philosophy and psychology programs) and appealed successfully to the Trustees for funding for laboratory equipment. Garman's emphasis in his courses on developmental psychology and pedagogy shows that he viewed his students not only as learners but as future teachers as well.

His courses were amongst the most popular at the College. Garman commanded deep loyalty from his students and his teaching exercised a strong, and sometimes lifelong, influence on them. Twice, in 1906 and in 1910, his students organized books of essays, reminiscences, and unpublished writings dedicated to their teacher. Garman apparently also had a reputation within the broader philosophical community and was known to William James and John Dewey.

In 1890, President Gates arrived at Amherst and took Seelye's position in philosophy. (Many Amherst presidents have had deep interests in philosophy. Most recently, President Tom Gerety, who received a joint doctorate in philosophy and law from Yale, was a member of the Philosophy Department and taught a course in the First-Year Seminar program called "Three and a Half Philosophers".) Gates clearly hoped to teach ethics and religion. Garman, however, was loathe to give up those subjects and wrote to the Trustees complaining of the situation. He resigned and was offered a position at the University of Michigan. The Trustees and alumni did not want to lose Garman and made him an attractive counter-offer, which included full control over the teaching of philosophy at the College. (Plus ça change ….) Garman accepted and returned in the fall of 1894.

In 1903, the College moved from a three- to a two-semester format. At the time of Garman's death in 1907, there were three courses in philosophy taught at Amherst: "Psychology and Pedagogics" and "Psychology and Sociology" to the Juniors, and "Ethics and the History of Philosophy" to the Seniors.

The Newlin Years

William Jesse ("Dutch") Newlin, Class of 1899 and one of Garman’s students, took over philosophy teaching in 1902 after Garman’s death, even though his training was mostly in mathematics. In 1908, Frederick Woodbridge, Amherst graduate and co-founder of The Journal of Philosophy, lent Newlin a helping hand to smooth the transition. (Woodbridge was based at Columbia and this would be the first of many Amherst-Columbia philosophy links that continue to the present day.) In 1909, Charles Toll was appointed Assistant Professor of Philosophy, although he taught courses in psychology. The academic year 1912-13, which Newlin spent at Oxford studying philosophy, saw the appointment of Alexander Meiklejohn as President of the College. Both Newlin and Toll taught at the College until 1948.

Alexander Meiklejohn

Meiklejohn had been an undergraduate at Brown and a graduate student in philosophy at Cornell. (This marks the first of many Amherst-Cornell philosophy connections that still remain strong.) Meiklejohn was a powerful intellectual figure and an eminent Kant scholar (his work is referenced in John Rawls' A Theory of Justice). Before arriving at Amherst, he had been teaching at Brown and serving as a dean there. When he joined Amherst as President, he was also made a member of the philosophy department, like Seelye, and he was given the title Professor of Logic and Metaphysics.

From the outset, Meiklejohn took an active role in guiding and teaching philosophy at Amherst. He, Newlin, and Toll were responsible for most of the teaching, though others were brought in as needed. One of these was Clarence Ayres, an ex-student of Meiklejohn's, who taught on and off at Amherst beginning in 1915, but only received a regular teaching position in 1920.

Meiklejohn was a controversial figure, and in 1923 he was asked to resign. He did and was followed by Ayres (as well as by thirteen other members of the Faculty who offered their resignations out of loyalty to Meiklejohn). Meiklejohn went on to direct the Experimental College in Madison, Wisconsin, and subsequently became a forceful and important defender of free speech (notably during the so-called "McCarthy Era").

The Post-Meiklejohn Era: Kennedy and Lamprecht

Philosophy was left shorthanded, and President George D. Olds brought

Stability finally returned with the appointments of Gail Kennedy (Ph.D., Columbia) in 1926 and Sterling Lamprecht (Ph.D., Columbia) in 1928. Combined, they taught for 70 years at Amherst: Lamprecht until 1956 and Kennedy until 1968. In addition to being effective teachers, Kennedy and Lamprecht were, unlike Newlin, active and publishing scholars: Kennedy an expert on Pragmatism, Dewey and Mill, and Lamprecht on Locke and Ancient Greek philosophy.

In 1933, primarily for bureaucratic purposes, the departments of philosophy, psychology and religion were merged into a single department. In 1939, psychology broke away and formed its own department, which Toll, who had been the College's sole psychology professor since 1928, joined. The departments of philosophy and religion were finally divorced in 1973.

The Post-World War II Era

During the Second World War, the College set up a committee on long-range planning to map out a course to follow when the war ended. Kennedy was co-author of this committee's report (1945) which led to the adoption of the famous New Curriculum instituted in 1946 by the faculty and the newly appointed President of the College, Charles W. Cole. (The definitive description of this program is to be found in Education at Amherst – The Program, co-authored by Gail Kennedy.) The most salient feature of the program was a series of courses, required of all undergraduates in the freshman and sophomore years, taught by instructors recruited from the various departments of the College. Kennedy, for example, regularly taught in the American Studies course required of sophomores. This meant that no one could devote full time to the teaching of philosophy anymore, so staff had to be added to the department – which was also feeling pressure towards further professionalism at this time. In 1952, Joseph Epstein (Ph.D., Columbia) was added to the staff. Until his retirement as George Lyman Crosby Professor in 1987, Epstein not only taught logic and the philosophy of science, as well as a famous seminar on Pragmatism, but he regularly taught in the Humanities course required of all freshmen. (He continued to teach in the successor courses to those required by the New Curriculum – as did other members of the Department.)

When Sterling Lamprecht retired in 1956, William E. Kennick (Ph.D., Cornell) was brought as an associate professor from Oberlin to take his place. Like Epstein, Kennick was a regular member of the staff of the required Humanities Program; in the philosophy department, he also taught the standard courses in the history of philosophy, as well as aesthetics, metaphysics, and a seminar on Wittgenstein. Kennick retired as the G. Henry Whitcomb Professor of Philosophy in 1993.

The faculty in philosophy was enlarged with the appointment in 1957 of Kai Nielsen (Ph.D., U. of North Carolina) who taught mainly ethics and philosophy of religion. Nielsen left in 1960 and was succeeded by Robert Tredwell (Ph.D., Yale) from 1963 to 1967; by Gerald Barnes (Ph.D., Cornell) from 1966 to 1971; and by Jeffery Sicha (D. Phil., Oxford) from 1968 to 1973. The instability of the fourth-person position, signaled by this series of non-tenure-track appointments, was remedied with the appointment of Thomas R. Kearns (Ph.D., U. of Wisconsin; LL.B., U. of California at Berkeley) in 1972. Kearns assumed primary responsibility for courses in ethics, social philosophy, and philosophy of law. He became the first William H. Hastie Professor of Philosophy and was one of the co-founders of the program (eventually, the Department) of Law, Jurisprudence and Social Thought, in which he taught half-time.

Since Kearns had in effect occupied the vacancy left by the retirement of Kennedy, the Department still had a fourth position to fill. It was first occupied by Elizabeth Victoria Spelman (Ph.D., Johns Hopkins), from 1973 to 1980. She introduced courses in the philosophy of mind and in feminist theory. She was succeeded by Willem de Vries (Ph.D., U. of Pittsburgh), from 1979 to 1986, an authority on the philosophy of Kant and Hegel, and on cognitive science. He was succeeded in turn by Jonathan Vogel (Ph.D., Yale) in 1986, whose main areas of interest were epistemology and the philosophy of Kant.

Expansion

With the prospect of Epstein's retirement looming, in the late 1980s, an outside committee was appointed by the Dean of the Faculty to examine Amherst's program in philosophy and to make recommendations for possible improvement. It recommended that the department be increased in size by one person. In 1988, in part to take Epstein's place, Alexander George (Ph.D., Harvard) was appointed. He assumed the instruction in logic and philosophy of science, as well as in the philosophy of language and philosophy of mathematics. The fifth position was then occupied a year later by Jyl Gentzler (Ph.D., Cornell), a specialist in ancient philosophy, as well as in health care ethics and feminist theory. With Kennick's retirement in 1993, she and Vogel assumed responsibility for Philosophy 17 and 18, the basic sequence of courses in the history of philosophy. From 1988 until 1998, the Department also counted Robert Gooding-Williams (Ph.D., Yale) among its ranks; he taught half-time in the Department of Black Studies.

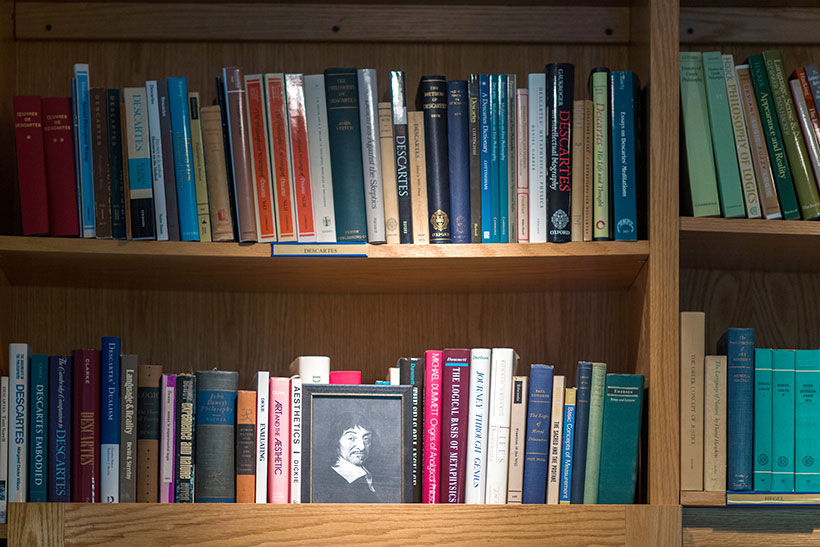

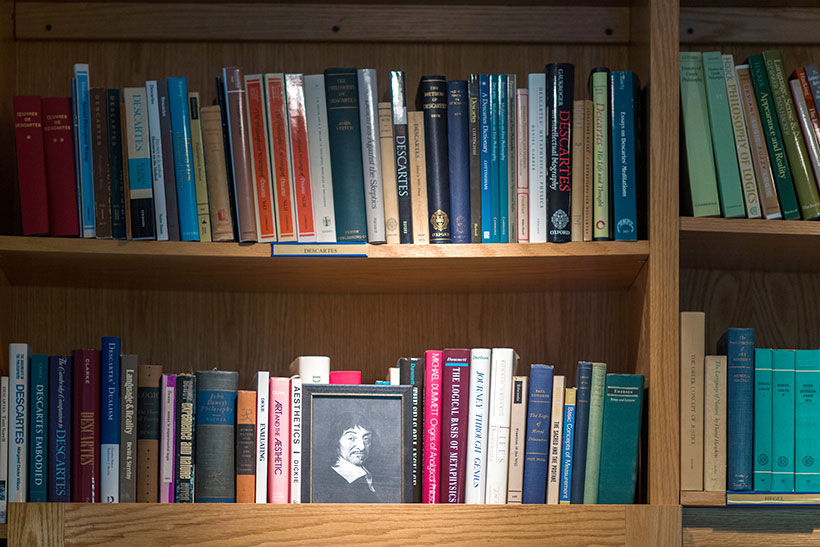

In 1988, for the first time in its history, the Department was gathered together in one location, the third floor of Williston Hall. At that time, the College also made space available for a reading and seminar room, subsequently named "The Kennick Reading Room" upon donation by Kennick of his philosophical library. In 1993, Joseph Moore (Ph.D., Cornell) was hired to teach philosophy of mind, as well as courses in decision theory and environmental ethics. As Kearns' retirement approached, the Department hired Nishi Shah (Ph.D., U. of Michigan) in 2001 to teach the central courses in ethics. In the fall of 2002, the entire Department was moved from Williston Hall (which was then converted to a dormitory for first-years) to Cooper House, a large house that had long served as Faculty accommodation, thoroughly renovated during the first half of 2002.

For the first time, the Department received a Keiter Fellowship, a post-doctoral position, and awarded it to Matthew Silverstein '98 (Ph.D., U. of Michigan), who taught from 2007-9. A Keiter Fellowship was again made available from 2010-12 and held by Ekaterina Vavova (Ph.D., MIT).

The Department grew to five full-time faculty members with the appointment of Rafeeq Hasan in 2015 (Ph.D., University of Chicago), whose areas of focus include social and political philosophy, and Kant. A further expansion to six members took place when Lauren Leydon-Hardy joined its ranks in the Fall of 2019; she received her doctorate from Northwestern and specializes in epistemology.

[Some of this information was gathered from Chris Peters' (Class of 1994) informative study "Philosophy at Amherst: 1880 to 1941." Photographs courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections.]