Lisa Stoffer, Amherst’s director of foundation and corporate relations, is co-author, with Hampshire College Professor Michael Lesy, of the new nonfiction book Repast: Dining Out at the Dawn of the New American Century, 1900–1910 (W.W. Norton & Co.).

Lisa Stoffer

The idea for the book arose several years ago, while Lesy (Stoffer’s husband) “was on an advisory committee for the New York Public Library, looking at their digital collections,” she says. “One of those collections is the Miss Frank E. Buttolph Menu Collection, and he was amazed by how beautiful they were.”

“Miss Frank E. Buttolph (1850–1924),” the NYPL website explains, was “a somewhat mysterious and passionate figure, whose mission in life was to collect menus”—more than 25,000 of them, primarily from restaurants in New York.

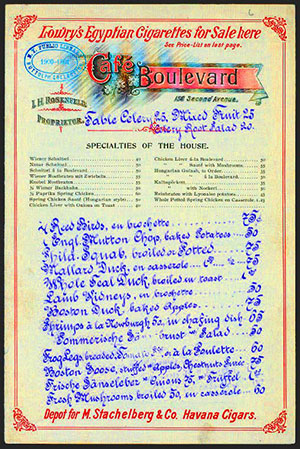

This menu from a New York City café, dated 1900, is one of thousands in the Miss Frank E. Buttolph American Menu Collection, 1851-1930, at the New York Public Library. It is featured in Stoffer and Lesy's book.

“Around the same time, through family members, I inherited a collection of menus and cookbooks from my grandfather and great-grandfather,” Stoffer continues. Her great-grandfather had been a chef in a hotel in Bermuda in the early 1900s, and her grandfather and grandmother (to whom Repast is dedicated) met when they were working as a cook and a waitress at Amherst’s Lord Jeffery Inn several decades later. “And we put the two things together, and we realized that there were some stories there. There was a set of stories about what was happening in society, and there was also a set of stories about what was happening in restaurants. So that became the idea for the book.”

Stoffer and Lesy were able to do most of their research through various libraries’ digitized archives of newspapers and magazines from the early 20th century.

Through original text interspersed with historical photographs and images from Buttolph’s menu collection, Repast illustrates the ways in which the restaurant industry and the practice of “dining out” changed rapidly between 1900 and 1910, “and the ways that those changes reflect bigger social changes that were going on,” says Stoffer.

Those years, for instance, brought the widespread industrialization of the U.S. food supply. Canned goods and processed meat were becoming commonplace. But these weren’t always pure or safe, and so there was a public outcry for stricter government regulations on the production, packaging and sale of food.

At the same time, millions of people, many from rural America and foreign countries, were flocking to the nation’s cities to take manufacturing jobs. These workers had short lunch breaks, necessitating the rise of “automat” food-vending systems, as well as “quick food” restaurants and lunch counters, which Stoffer calls “sort of the predecessors of Friendly’s or McDonald’s.” Notably, the workforce was attracting women in ever-greater numbers, on every rung of the socioeconomic ladder—from factory workers, to doctors and lawyers, to community leaders—and ladies’ lunch clubs sprung up to provide them with safe and comfortable places to eat, away from the company of men.

This era also saw enticing innovations in fine dining for well-to-do Americans.

Promotional photo for the Childs restaurant chain, dated 1900. “They made their name in large part on the sparkling cleanliness of their dining rooms (all that tile and those marble countertops) and on their friendly, super-efficient waitresses with pristine white uniforms," says Stoffer. “This was a departure—other ‘quick lunch’ places that preceded them were known for being grungy with sassy, sometimes surly service.”

With chapters on “Pure Food,” “Quick Food,” “Her Food,” “Other People’s Food” and “Splendid Food,” Repast has drawn attention from food-history bloggers and even The Boston Globe.

Top photo by Rob Mattson; middle image from the Miss Frank E. Buttolph American Menu Collection, 1851-1930, at the New York Public Library; bottom photo by the Byron Company