Deceased September 2, 2010

View alumni profile (log in required)

Read memorial

In Memory

Bruce A Warren, '58's oceanographer par excellence, died suddenly September 2, 2010, of a heart attack while vacationing with friends in Provincetown, MA. He was 73.

Bruce is remembered fondly by his classmates – self-effacing yet brilliant, unfailingly courteous, kind, gentle, and warm, quick to laughter, greatly respected, thoughtful, at home with himself, a true scholar, easy to live with.

The Amherst images of Bruce in our minds remain bright. Steve Maling remembers him reading German novels for the pleasure of it and taking one credit hour German courses over several semesters to maintain and strengthen his language skills. Steve credits Bruce with introducing him to the writings of Rudolf Bultmann, the German Protestant theologian, but hastens to add it was the translation, not the original. Rich Noer, his roommate senior year (with Dave Scott) recalls his sense of style: the night before their weekly French class, he would light up his pipe, turn on Ravel or Fauré, pour glasses of Chianti from the straw-covered flasks of the time, as they settled down peacefully to read their Proust. Mike Spero says he will smile whenever he thinks of Bruce. He recalls a conversation he and Joan had with Bruce where she admitted wondering on first going abroad whether relatives there would have access to toothpaste. A week later a letter arrived from Bruce with a small tube enclosed. And Michael, Bruce’s surrogate son, tells how for forty years Bruce would send him some kind of witty or humorous missive commemorating the May, 1453,. fall of Constantinople.

Bruce was a "stayer." He spent his entire professional career at a single institution,the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). How did he get there? The Arnold Arons connection . . . but it quickly became far deeper than just a case of proximity in his freshman year. Arons, who worked at Woods Hole in the summer, suggested to Bruce that a bright young friend of Arons, Hank Stommel, had a lot of routine chores that needed doing. The Cape in summer sounded fun to Bruce, and when halfway through the summer the chores evaporated, Stommel sent Bruce off to sea with Fritz Fuglister on the Atlantis. "I loved that," Bruce said. Arons, Stommel, and Fuglister became Bruce’s mentors.

institution,the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). How did he get there? The Arnold Arons connection . . . but it quickly became far deeper than just a case of proximity in his freshman year. Arons, who worked at Woods Hole in the summer, suggested to Bruce that a bright young friend of Arons, Hank Stommel, had a lot of routine chores that needed doing. The Cape in summer sounded fun to Bruce, and when halfway through the summer the chores evaporated, Stommel sent Bruce off to sea with Fritz Fuglister on the Atlantis. "I loved that," Bruce said. Arons, Stommel, and Fuglister became Bruce’s mentors.

But the Arons connection would turn out to be far deeper than just a lead on a summer job. One of the outcomes of the Stommel/Arons work together was a theory (which bears their names) concerning the behavior of deep ocean currents. A series of papers from 1958 to 1960 laid the foundation for our present understanding of deep ocean circulation but it differed so greatlyfrom what was expected that Stommel and Arons actually had to devise laboratory experiments with rotating fluids to confirm their theory. Bruce always thought it was his especially good fortune to come along at just the right time. The Cold War dramatically increased support for scientific research. Plus, a new theory proposing radically different ocean circulations from what had been imagined made physical sense, and it begged to be tested. It seemed, he later said, "a worthwhile thing to do." And he did!

of the outcomes of the Stommel/Arons work together was a theory (which bears their names) concerning the behavior of deep ocean currents. A series of papers from 1958 to 1960 laid the foundation for our present understanding of deep ocean circulation but it differed so greatlyfrom what was expected that Stommel and Arons actually had to devise laboratory experiments with rotating fluids to confirm their theory. Bruce always thought it was his especially good fortune to come along at just the right time. The Cold War dramatically increased support for scientific research. Plus, a new theory proposing radically different ocean circulations from what had been imagined made physical sense, and it begged to be tested. It seemed, he later said, "a worthwhile thing to do." And he did!

Using the Stommel/Arons theory for strategic guidance,  Bruce set about the life-long task of studying the deep Pacific and Indian Oceans in a series of long and distant exploratory cruises.It was a life’s work whose success was to be recognized in 2004 by the American Geophysical Union’s award of the Maurice Ewing Medal for significant contributions to the scientific understanding of the processes in the ocean; for the advancement of oceanographic engineering, technology, and instrumentation; and for outstanding service to marine sciences. More recently, the American Meteorological Society bestowed on Bruce the 2010 Sverdrup Gold Medal "for advancing our understanding of the general circulation of the ocean through observations and dynamical interpretation."

Bruce set about the life-long task of studying the deep Pacific and Indian Oceans in a series of long and distant exploratory cruises.It was a life’s work whose success was to be recognized in 2004 by the American Geophysical Union’s award of the Maurice Ewing Medal for significant contributions to the scientific understanding of the processes in the ocean; for the advancement of oceanographic engineering, technology, and instrumentation; and for outstanding service to marine sciences. More recently, the American Meteorological Society bestowed on Bruce the 2010 Sverdrup Gold Medal "for advancing our understanding of the general circulation of the ocean through observations and dynamical interpretation."

Bruce was in his element at sea – a meticulous observationalist. (While some ascribed his rigorous habit of mind to his association with Arons, his brother Robert described his discovery in Bruce’s papers of every bank record and check stub going back to his brother’s first account in high school. Arons may have help extend it but the precise habit of mind was well established early!) He was also an excellent shipmate. Bruce put it simply: "I like to go to sea and I like the company of people who like to go to sea." His Amherst classmates speak of the pleasure of their interactions with him, but those who sailed with him enjoyed equally relaxed and stimulating conversations on diverse topics. History, for example. Michael Ashmore says he could recite all the names of the Byzantine Emperors for the millenium they were in power. Or gardening. In the last several years in our newsnotes phone calls he and I would commiserate or gloat over the results of our respective gardening efforts. He talked ornithology, or literature, or cultural variations in social approaches to spiritous libations.

Back on land, Bruce (as memorialized by five of his oceanography colleagues) was equally deliberate with his interpretation of data. While he had email, he himself didn’t use computers; he was one of the last scientists whose work was done in person, on site, making the contemporary processes of remote data collection and computer modeling a major departure from where he started. His aids were pencil-and-paper, a drafting table, a rocking chair, and a pipe. He was not a solitary scientist, though; he enjoyed his colleagues in the Clark Laboratory reading room, coffee breaks, erudite conversations, with a sea story thrown in now and again. He loved language, published at least 53 refereed papers, served as an editor of three volumes, and coedited the Journal of Physical Oceanography (1980-85).

Obviously, Bruce had interests besides the ocean, science, and the sea. He was an avid naturalist keeping an illustrated notebook of Cape Cod wildflowers. He loved classical music. He was an epicure fond of a well prepared meal, a stiff drink, and good company. A colleague remembered frequent visits to Chillingsworth, one of the Cape’s Michelin restaurants, where he would be recognized by the staff by name at the annual wild game dinners and be served without having to be asked the particular formulation of martini of which he was fond. That’s probably what lay behind the commission he undertook for the local Historical Society to write a chapter entitled "Bars of Woods Hole," in one of which, Captain Kidd’s Restaurant, WHOI held a very well-attended memorial gathering which included Fred Greenman and me. (That was not Bruce’s only entry into the genre. On his own he submitted and published an article regarding geographical variations in gin-and-tonic garnishing customs!)

He was an avid naturalist keeping an illustrated notebook of Cape Cod wildflowers. He loved classical music. He was an epicure fond of a well prepared meal, a stiff drink, and good company. A colleague remembered frequent visits to Chillingsworth, one of the Cape’s Michelin restaurants, where he would be recognized by the staff by name at the annual wild game dinners and be served without having to be asked the particular formulation of martini of which he was fond. That’s probably what lay behind the commission he undertook for the local Historical Society to write a chapter entitled "Bars of Woods Hole," in one of which, Captain Kidd’s Restaurant, WHOI held a very well-attended memorial gathering which included Fred Greenman and me. (That was not Bruce’s only entry into the genre. On his own he submitted and published an article regarding geographical variations in gin-and-tonic garnishing customs!)

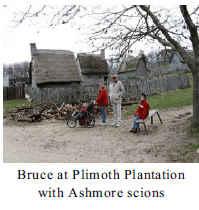

Bruce never married. But he was not without a real, deep, and lasting family connection. In the fall of 1960 Bruce moved from WHOI summer housing into a rental with his friends, Judy and Herb Ashmore and their one-year old daughter Jill. This arrangement would continue through the birth of three more children, Beth, Michael and Lynne, and two houses. When Herb’s job required him to leave for work almost before the kids were up, Bruce often filled in making their "eggies and toast" (and, yes, he watched Captain Kangaroo with them, too). By 1967 he was ready for more peace and quiet (and the Ashmores could use the space!), and Bruce moved to the apartment he lived in the rest of his life. When Herb succumbed to illness only five years after his last child was born, Bruce continued in his role as friend and "uncle" to his surrogate family of the Ashmore children and, as the decades rolled by, to their children as well. He took the Ashmore children on trips to Bruce’s parent’s camp on Lake Moxie in Maine – berry picking, gardening, hiking and birding with them – and introduced them to music, art, literature and history, all Bruce’s favorites. Judith Ashmore, Michael’s mother, said of Bruce there was never an ocean current he didn’t like; he would go to the ends of the earth to examine one. And he did!

required him to leave for work almost before the kids were up, Bruce often filled in making their "eggies and toast" (and, yes, he watched Captain Kangaroo with them, too). By 1967 he was ready for more peace and quiet (and the Ashmores could use the space!), and Bruce moved to the apartment he lived in the rest of his life. When Herb succumbed to illness only five years after his last child was born, Bruce continued in his role as friend and "uncle" to his surrogate family of the Ashmore children and, as the decades rolled by, to their children as well. He took the Ashmore children on trips to Bruce’s parent’s camp on Lake Moxie in Maine – berry picking, gardening, hiking and birding with them – and introduced them to music, art, literature and history, all Bruce’s favorites. Judith Ashmore, Michael’s mother, said of Bruce there was never an ocean current he didn’t like; he would go to the ends of the earth to examine one. And he did!

That makes especially fitting his colleague’s intentions respecting Bruce’s ashes. They will be encapsulated in a small container (along with a small pad and pencil, Bruce’s preferred analytic mode), release it at a depth of 3000 meters, and allow his remains to follow in perpetuity the paths of the deep ocean currents he helped to define and understand.

Hendrik D. Gideonse ‘58

Source note: Many people helped to bring this together either because I talked with them, read what they wrote, or both.. Those not mentioned in the text include Breck Owens and John Toole (WHOI), Gregory Johnson (NOAA/Pacific Environmental Laboratory), Kevin Speer (Florida State University), Joseph LaCasce (University of Oslo), Robert Stewart (Texas A&M), Jonathan Helmreich, and Fred Greenman. WHOI provided the “at sea” photos.