The first editor, John Franklin Genung, came to Amherst in 1882 to teach English and biblical literature. In addition to his teaching duties, he edited the Amherst Graduates’ Quarterly until his death in 1919.

By Emily Gold Boutilier

Don’t let the volume number on the Table of Contents fool you—the 100th anniversary of Amherst magazine is this fall. The enterprise began in October 1911 when alumni underwriters published the first issue, then called the Amherst Graduates’ Quarterly. Renaming it the Amherst Alumni News in 1949, the editor also reset the clock—to Volume 1, Issue 1. (The name changed once more, to Amherst, in 1971—although mail still arrives addressed to the old titles.) Name and number aside, this quarterly publication has been telling the stories of Amherst and its alumni for a century and counting. The pages that follow contain 10 decades’ worth of news, photos and commentary plucked from past issues. Taken together, these items are a lesson (however incomplete) in college history and alumni achievements, but more than that, they say something about how a small college on a hill in a valley has both reflected and shaped the changing times.

1910s

Not in “good taste”

[1911] Volume 1, Issue 1, opens with a note on modesty: “We do not deem it good policy or good taste,” writes editor John Franklin Genung, “to say much about ourselves.” Inside the 91-page Amherst Graduates’ Quarterly is a report on athletics (“The football season of 1910 was a superlative argument against the Jeremiahs who prate of a loss of college spirit at Amherst”) and a dense, footnoted essay, “The Enterprise of Learning,” which quotes Aristotle—and not in translation. Then as now, class notes report on marriages, babies, job changes and reunions. “The wives of 1905 were the greatest attraction of Commencement week,” declares the (perhaps biased) secretary of the Class of 1905.

The expedition of Professor Loomis

[1912] Frederick B. Loomis pens an article on his research trip to the Patagonia region of South America: “On August 9 we sailed for Puerto Madryn, where we expected to buy horses and make a start,” writes the geology professor. “Fate willed otherwise. Suitable horses were not to be found.” His team eventually uncovers bones from “early members of the monkey, armadillo, horse, and guinea-pig families,” and a complete skull of an animal “considered to be the ancestor of the modern elephants” and closely resembling the Palaeomastodon from Egypt. This suggests to Loomis “that some of the South American animals originally came from Africa.”

During World War I

In 1918, the Students’ Army Training Corps drilled in front of the new Converse Library. During World War I, the magazine ran lists of alumni servicemen.

|

[1917] A fraternity votes to “give up its initiation banquet and dance, thereby crushing at one move an extravagance and a distraction,” says the Quarterly, which begins to list “Amherst Men in the National Service.” The magazine remembers the Civil War, when “a mock ceremony was arranged by several students who marched about the streets of Amherst pretending to represent the funeral of Jefferson Davis. … We little thought then that in later years we should enter a world conflict.” In other news, many believe that Massachusetts Lieutenant Governor Calvin Coolidge ’95 “will be the gubernatorial candidate a year hence.”

Stirring up trouble

[1918] “Here’s a question for debate,” writes Genung. “How much attention should a college of liberal arts pay to the so-called fine arts? Is there anything wrong with a college that has produced one great architect, one great playwright, and a mere corporal’s guard of artists, musicians, and men of letters scattered through the honorable ranks of successful business men, educators, men of affairs, doctors, lawyers, and clergymen? To be specific, should Amherst College do more to foster an appreciation of beauty, as well as of science and learning, as a part of the higher culture? We have heard mild criticisms along this line. If any Amherst alumnus has a conviction on this point, let his voice be heard.”

History lesson: Converse Memorial Library, named for “an eminent capitalist of New York”—Edmund Cogswell Converse ’67—opens in 1918. Quarterly editor Genung writes: “The graduate misses much if in addition to his cum laude diploma he fails to leave college a self-determined and disciplined bookman.”

1920s

Coolidge on Amherst

During the 1920s, the Quarterly devoted much attention to Calvin Coolidge ’95, the first and so far only U.S. president to come out of Amherst.

|

[1921] Amherst marks its centennial with speeches and an “Alumni Open Air Smoker,” a type of banquet popular at the time. Calvin Coolidge, who had become U.S. vice president the previous year, contributes an essay to the Quarterly on the college’s founding: “We can see in retrospect how truly American this purpose was, how it runs back to the spirit of the Mayflower.” Meanwhile, editor George F. Whicher ’10 pines for the good old days, complaining, “What is the Faculty coming to? Its invariable law seems to be that of deterioration.”

Silent Cal’s ascent

[1923] Coolidge becomes president. “In college Coolidge was quiet, retiring, but always thoughtful,” writes Charles A. Andrews ’95. “[His] recitations were always good, but he seldom volunteered or got into the general discussion. His intimates were few. His participation in ‘outside activities’ was negligible, and yet he was neither aloof [nor] lonely.” According to Andrews (who fails to elaborate), Coolidge’s “earnest approach to athletic renown was the fact that he was one of ‘the last eight’ who paid for the oyster supper after the ‘plug hat’ race in junior year.”

Not all golf and bond-salesmanship

In 1925, students were allowed to skip chapel a certain number of times per semester. When the administration announced plans to end the allowance, students converged near Johnson Chapel in protest.

|

[1928] To show that “the college graduate’s life is not all golf and bond-salesmanship,” the Quarterly documents the experience of Arthur F. Tylee ’18, a missionary in Brazil who lives “about five hundred miles beyond civilization,” near members of the Nhambigquaras tribe. “Their extreme primitiveness’’—they have no shelters and wear no clothing—“is coupled with an apparently high moral standard and a wholesome family life.”

No more dumbbells

[1929] Gym class isn’t what it used to be. “To many Amherst men the dumb-bell was an object of suspicion,” writes physical education professor Allison W. Marsh ’13, “being the symbol of mass compulsory drill and a missile much to be feared. Gone are the dumb-bells and the class drills; in their place are boxing gloves, handballs, squash rackets, and small classes.”

As advertised: In 1926, an ad for General Electric (the magazine ran advertisements through the 1940s) proclaims electricity “the great emancipator,” explaining, “With service so cheap and accessible, no wise husband or factory manager now leaves to any woman any task which a motor will do for a few cents an hour.” More than half of U.S. homes now have electricity, the ad says.

1930s

Prohibition poll

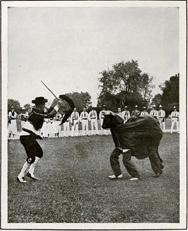

Between innings at the Amherst-Williams baseball game on June 13, 1934, reunion classes staged two rival “bull fights.”

|

[1930] Of 496 students polled, 285 are for modifying Prohibition laws in the United States, 122 are for total repeal, 77 are for strict enforcement and 10 are for “retaining the present system.” In answer to the question “Do you ever drink?,” 357 Amherst men reply “yes” and 139 say “no.” Of the latter, eight mention legal restrictions and 126 cite personal taste as the reason for abstaining. “Students, at Amherst at least, seem to have realized that when a dance is on, liquid joy had better be confined,” the magazine affirms, “and the conviction that a gentleman who cannot hold his liquor is wiser not to try to hold any appears to be spreading.”

Latin no longer required

The November 1934 issue included a photo of Professor Arthur J. Hopkins ’85 in his laboratory.

|

[1933] Amherst President Stanley King announces “radical changes” in entrance requirements. It’s now permissible “for a promising student to enter Amherst without Latin,” though preference will still be given to those who, among other things, have multiple years of foreign language instruction, “ancient preferred.” Editor Walter A. Dyer ’00 pulls no punches in his commentary: “The editor of the Quarterly, speaking for himself alone, is regretful.”

Distracting feminine loveliness

[1933] Fraternities adopt “uniform regulations controlling the presence of women in their houses.” Female guests must leave by 7:30 p.m., except on Saturdays and Sundays, when they may stay until 11. “The problem of what to do about the distracting presence of feminine loveliness on masculine campuses has become acute,” editor Dyer explains.

“Hurricane Class” gets windy welcome

A 1938 hurricane destroyed about 150 campus trees, some as old as the college, reported the magazine.

|

[1938] Some 150 campus trees are destroyed in a Sept. 21 hurricane; classes are suspended for the first three days of the term. “Hardly more than an hour after a new entering class, full of life and hope and doubtless some mystification, had been welcomed in Johnson Chapel by the President, the hurricane struck with full force and laid low our beautiful and majestic trees, some of them as old as the College,” reads an account by editor Dyer. “Returning alumni will never again see their beloved Grove as it was.”

History lesson: Henry Thomas Rainey ’83, elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1920, is chosen as speaker of the House in March 1933. He dies a year later.

1940s

Slipping through Nazi fingers

[1941] Thomas O. Greenough ’33, an ambulance driver for the British-American Ambulance Corps, is on board the Egyptian steamship Zamzam when a German raider sinks the ship and takes the Americans. Held for two months, Greenough escapes from a Nazi-guarded train in France. “Suddenly a dark form stepped from a doorway,” he recalls. “To run would have been futile, so we steadily advanced. ‘Halte! Haben sie papieren?’ We halted; obviously we had no papers. … I answered in French: ‘Of course not; we work in the station. Don’t you recognize us?’” Greenough reports to Quarterly readers that “the power and organization of the German system is far greater and more complete than we, in this country, would wishfully believe.”

Another world war

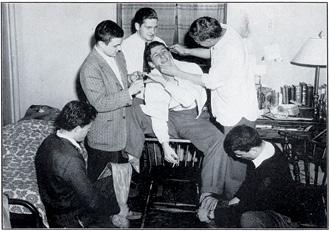

The night before he departed to join the U.S. Army, Stuart Arnold ’46 received a manicure, shoeshine and G.I. haircut.

|

[1942–44] Amherst adopts an accelerated program, including a summer session, for future servicemen. “Until a student is actually called to join the armed forces, his one compelling job is to get as much education as he can,” writes editor Dyer. Starting in 1942, eight military units use the college for training, a reality that James Merrill ’47—who would become one of the leading poets of his generation—writes about in the February 1944 Quarterly: “We still smile as we curse the Army and Navy for having taken over the College with fiendish thoroughness, and our delight is tempered with incredulity when we actually meet a fellow-student upon the campus.”

We are young. We are youth.

[1943] Merrill contributes an essay on being an Amherst student during wartime. “We are young. We are youth, loved by the world and half-forgotten by it,” he writes. “We are convinced of many things: that the world will always love us, that we will always love it, that we will never grow old. We are almost desperately convinced of these things now, as one by one parts of us are called away from what is familiar to us.”

Fresh, forward-looking vitality

Above: Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, seen with history professor E. Dwight Salmon, came to Amherst on July 11, 1946, to inspect the War Memorial.

|

[1949] Two years into the job, editor Horace W. Hewlett ’36—who will hold the position for 30 years—unveils a major redesign of the magazine, which is renamed the Amherst Alumni News. President Charles B. Cole writes of the magazine: “May it inspire every alumnus to return to the campus. May it keep alive memories of Amherst among those who cannot come back. May it bring to every Amherst man a direct sense of the fresh, forward-looking vitality of our one hundred twenty-eight year old alma mater.”

As advertised: A 1940s ad for General Electric depicts a woman in an apron opening a refrigerator door. The tagline asks, “How many times each day does she open it?” The answer, according to GE, is 35 to 70.

1950s

On choosing a wife

[1950] A new psychology course that covers “family and marital relations” might “draw some of its material from notes taken by an Amherst student in the 1860s,” reports the Alumni News. Entitled “Suggestions in relation to choosing a wife,” these 19th-century notes advise that a man “look out for a tendency to any hereditary diseases,” including, but not limited to, “St. Vitus Dance & scrofula.” Also: “never marry a blood relation.” The May 1950 class notes are a mere two pages—“for budgetary reasons,” the editor explains.

Student cracks code for separating rock

A scene from a 1950s Amherst College bonfire.

|

[1950] Donald G. MacVicar Jr. ’51 solves “a problem that has baffled scientists for many years,” the magazine writes. “By developing a process for separating rock, he has broken a barrier which has, up to now, limited the time period for study of remote life. Until the present, the oldest authenticated fossil remains of living organisms dated back to six or seven hundred million years ago. MacVicar’s new method”—which even earns a write-up in Time—“has already disclosed specimens of ancient life estimated by Professor of Geology George W. Bain to be nearly one billion years old.” Sadly, MacVicar dies only five years after his graduation.

Professor discovers antioxidant

[1953] Professor George W. Kidder and associates in the biology department discover a vitamin, thioctic acid, in the B complex group, “which Dr. Melvin Calvin, noted biochemist of the University of California at Berkeley[,] rates second to chlorophyll in importance today,” says the magazine, which does not elaborate on what Calvin means by “importance.” (In the 21st century, this antioxidant is more commonly known as lipoic acid.)

Four holes in the Iron Curtain

In 1952, it was still a commencement tradition for students to plant ivy on campus.

|

[1955] Francis B. Randall ’52 and three others travel unescorted to the Soviet Union as tourists. “We saw cities that only one other American has seen in the last 10 years,” he writes. “We were four holes in the Iron Curtain.” Arrested 16 times, he describes Russia as a police state. “We would be taking pictures of some innocuous slum or other, when the police or the soldiers would pop out from behind a passing truck or camel, and march us off to the station for illegal photography.” Though he is always set free shortly thereafter, Randall expresses “an ever-so-faint suspicion that when a Soviet citizen gets arrested, he can’t just breezily refuse to sign the confession and walk out of the station.”

History lesson: In 1951, the college marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Melvil Dewey ’74, who copyrighted his famous Decimal Classification system while serving as an assistant librarian at Amherst in 1876.

1960s

Freedom Riders speak

The legendary football coach James E. Ostendarp in 1966.

|

[1961] Randall earns another byline in the Alumni News after he and Robert M. Brown ’43 separately participate in Freedom Rides in the South. “Small hostile crowds were out to meet us,” Randall writes. “The local police were usually out to protect us.” When they weren’t, “my wife and her partner tried to buy cokes at the lunch counter, [but] the waitress refused them service and fled. A white youth came in and threatened them with a long carving knife. … Where the police desire it, the South can be integrated without violence.”

Freedom Riders “immature,” “stirring up discontent”

[1962] “I see no reason whatsoever to devote a full page of the Alumni News to applauding two Amherst graduates … for their participation as Freedom Riders in the recent difficulty in the South,” reads one letter to the editor, which argues that other graduates are “far more worthy of individual attention and recognition than two immature and too apparently idealistic individuals who went far out of their way to join in stirring up discontent in a problem which, basically, was none of their business.” Other letter writers defend the riders and the magazine: “The Freedom Riders of today are just as much the proper business of Amherst men as the Anti-Slavery Society of 1837–38.”

Kennedy is shot

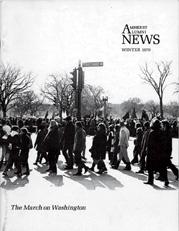

In November 1969, more than 300 Amherst students and faculty joined the March on Washington against the Vietnam War. “For those students who swayed gently together singing, ‘All we are saying is give peace a chance’ … there is a residual ray of hope,” wrote Lawrence Sidman ’70 in the magazine.

|

[1963] “Privilege is here, and with privilege goes responsibility,” says President John F. Kennedy in an October speech at Amherst, which is detailed in a special issue of the Alumni News. The next regular issue reports on Kennedy’s assassination, publishing an account by the United Press International’s Earl C. Dudley Jr. ’61. Dudley describes seeing the call letters “DA,” for “Dallas bureau,” on a wire bulletin in the newsroom and thinking, “I doubt if we need this; it’s probably just Kennedy arriving at the hall for his speech.” Then, Dudley writes, “I became for a few swift yet seemingly endless minutes an automaton, doing what I had to do to spread the tidings to a news-hungry world.”

Students protest McNamara

Some 20 graduating seniors walked out of the 1966 commencement ceremony when Amherst awarded an honorary degree to Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara.

|

[1966] The 145th Commencement becomes “unusually dramatic” when the college confers an honorary degree upon Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara. Some students and faculty members say the honor implies endorsement of the Vietnam War. McNamara meets with students before the ceremony to answer questions about the war and the draft. Thirty-six seniors wear white armbands over their graduation gowns. One, Elliott Isenberg, crosses the platform, stops, refuses to accept his diploma and quietly returns to his seat. When McNamara’s degree is conferred, some 20 graduating seniors walk out of the ceremony, at which point most of the audience gives the secretary a standing ovation. Isenberg is now a psychologist. He said in a 2011 class note that his Amherst diploma is likely the only one signed by two presidents.

History lesson: In 1962, Rose Olver becomes the first woman to hold a full-time, tenure-track teaching appointment at Amherst. Today, she is the L. Stanton Williams ’41 Professor of Psychology and Women’s and Gender Studies.

1970s

Amherst on strike

[1970] On May 6 the faculty votes to “formally declare its solidarity with the nationwide movement” protesting President Richard Nixon and the wars in Vietnam and Cambodia; class attendance becomes optional for the rest of the semester. “Amherst this spring found it logically impossible to continue peaceful ignorance of the atrocities of American civil and foreign policies,” writes undergraduate columnist Ronald D. Varney ’71. “Classes ended so that education could begin, about the war and about countless other things which Americans should and do care about.”

Freshman drowns in Pratt Pool

[1973] Gerald Gilbert Penny ’77 drowns in Pratt Pool on Sept. 12. James Warren ’74, the magazine’s undergraduate columnist, reflects on the tragedy: “The fact that it was a black Southern kid trying to prepare for a stupid swimming test at a white boys’ school up North and that the lifeguard was … well, you can guess, didn’t make things any better.”

Watergate. Watergate. Cambodia.

[1973] “We were inundated with Watergate,” writes Warren (now a Huffington Post columnist and alternative-weekly publisher) about his summer vacation. “Watergate. Watergate. Watergate. Watergate. Watergate. Cambodia. Watergate. Watergate. Wait, what was that about Cambodia? … Boys as old, if not younger than Amherst seniors, who wanted just like us to be doctors, lawyers, auto mechanics, insurance salesmen, baseball players, pilots, certified public accountants, fathers with little kids, got shot down over Cambodia, or were killed, mangled, or maimed in some other way, some crying out very painfully, perhaps even cursing out God or some communist, sobbing like little kids before … they died.”

It's official: Amherst is coed

Anita Cilderman ’76, a transfer student from Mount Holyoke, became the first woman to receive an Amherst B.A.

|

[1975] “The talk is over and the work now begins,” reports the magazine in 1974: The college will admit female students as transfers beginning with the 1975–76 academic year. At opening convocation in 1975, President William Ward urges that a female student not be referred to as a “coed” (“If she is, then men are also ‘coeds’”) and that, though a minority, women be “equal in the life of the College.” In 1976, nine women receive bachelor’s degrees from Amherst.

M.D., not J.D.

[1976] A survey of graduating seniors reveals that 20 percent plan careers in medicine, and that those students outnumber pre-law students for the first time since 1961. “Those interested in business careers dropped to 15 percent from last year’s all-time high of 23 percent,” says former Associate Dean of Students Henry Littlefield.

A new editor

[1977] Douglas C. Wilson ’62 is named editor of Amherst magazine upon the retirement of Horace Hewlett. Wilson, who will hold the position for 25 years, writes of Hewlett: “Those who had the pleasure of working most closely with him—seeing him write articles, edit galleys, crop photographs and measure page layouts—know how intensely this quarterly was one man’s quiet, devoted labor.”

Kamin on Uruguay

Members of the Class of 1980 whisked this Sabrina statue onto campus during the 1979 commencement ceremony.

|

[1978] Predating his career as Chicago Tribune architecture critic, Blair Kamin ’79 contributes an article, based on his journal entries, about a Glee Club tour of Latin America. He reports from Uruguay: “We drew a full house tonight. … Our hosts tell us that we are the first American students allowed on that campus since the political upheaval of the early ’70s. The crowd surprised me because Uruguay and the United States have reached a 40-year low point in relations. The heavily military dictatorship here strongly objects to President Carter’s human rights program.”

History lesson: On Aug. 7, 1974, future Amherst magazine editor Douglas C. Wilson ’62 of the Providence Journal is the first journalist to report Richard Nixon’s decision to resign as president.

1980s

College bans single-sex frats

A 1980 magazine cartoon stepped into the controversy over coed frats.

|

[1980] Trustees ban single-sex fraternities. The magazine quotes Elizabeth Biddle ’83, whose house is already coed: “We do our laundry together, we bring the wood in, we take the trash out. People see me as other than someone who’s just a romantic object. If we could get rid of that mystery about the female sex it would be easier for a lot of women on this campus.” Four years later, the trustees ban on-campus fraternities entirely.

FBI director: We’re after the car theft rings

[1984] Magazine staffer Terry Y. Allen profiles FBI director (and future CIA director) William H. Webster ’45, writing, “Many political commentators have credited him with restoring the Bureau, badly tarnished in the Watergate revelations, in the American public’s estimation.” Webster’s emphasis is on arresting big-time criminals, including leaders in organized crime. “We could still be chasing stolen cars,” he says. “Now we’re after the car theft rings.”

Sabrina doesn’t live here anymore

In 1981, Ted Conover ’81 wrote about traveling from Nevada to California as part of his anthropology thesis on “railroad tramps.”

|

[1985] The magazine prints “Sabrina Doesn’t Live Here Anymore,” a talk by feminist scholar and Amherst professor Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. “You’re still young,” she tells students, “in a society where men’s status and entitlement increase with age and women’s status and entitlement decrease with age.” In an obituary for Sedgwick in the Summer 2009 magazine, Professor of English Andrew Parker pays tribute to the article: “Enlisting as a feminist icon the nude female statue that had been both glorified and abused throughout its long association with the college, Sedgwick took stock of a campus culture that had neither fully welcomed its female students and faculty nor had begun to acknowledge its homophobia.”

“Sabrina” fallout

[1985] The “Sabrina” piece generates an abundance of letters to the editor. “Sedgwick’s whining at the wailing wall … has tilted my view of women at Amherst from total indifference to total hostility,” writes one alumnus. “With the ship of state seemingly drifting to destruction, we need the commanding voice of a Captain Bligh, not the whimpers of women who discover their sex, race, religion bar them from quarterdeck authority. Better to be a lower order aboard a ship on course than a cringing castaway.” Other letters praise the piece.

GALA draws venom—and praise

Laura Carrington ’80, who would become well known for her role as Dr. Simone Hardy on General Hospital, returned to campus in 1981 to act in a play.

|

[1986] A news item on the creation of the Gay and Lesbian Alumni group draws venom from letter writers. “An abomination! A disgrace to the college!” writes one alumnus. “Put them back in the closet, where they belong.” Such mail leads to more mail: “Thank you for publishing the article about Amherst GALA,” says one letter, “and for publishing the letters in response. The latter eloquently testify to the need for the former.”

History lesson: In 1987, trustees vote to divest of all securities in companies doing business in apartheid South Africa. Two years later, President Peter Pouncey decides not to renew the college’s contract with Coca-Cola, a move that follows a nonbinding student vote to ban the sale of the soft drink on campus because of the company’s support of the South African government.

1990s

Courtship ritual

[1990] “In an elaborate courtship ritual that would top any Valentine’s Day overture,” corporate recruiters spend thousands of dollars wooing Amherst seniors for hard-to-win jobs, according to a news report by Christopher Miller ’90. One investment bank promises “a lavish spread of dim-sum,” and second-round interviewees get the star treatment: fancy hotel rooms and, in one case, a two-block ride in a stretch limo. Students report being asked strange interview questions: “What are the last three records you’ve bought?” “Would tires wear out faster in Florida or California?” “Why is the start button on the back of a computer?” Of 1,082 on-campus interviews conducted at Amherst in 1989, the article says, 88 job offers are extended and 51 ultimately accepted.

A place of earning

Clarisa Gracia ’93 ran a hairdressing business out of her dorm.

|

[1991] Years before he started writing the personal finance column in The New York Times, Ron Lieber ’93 writes an Amherst magazine feature on student entrepreneurs. Clarisa Gracia ’93, a premed student, runs a hairdressing business out of her dorm. “I’m hoping it will be good for my bedside manner,” she tells Lieber. (She’s now an ob-gyn.)

Infinite Jest, reviewed

[1996] Sarah Markgraf ’84, assistant professor of English at Bergen Community College in New Jersey, reviews Infinite Jest, by David Foster Wallace ’85. “A number of young men are writing big books about technology, conspiracy, and irony these days,” writes a skeptical Markgraf. “The brilliance of these writers is undeniable, though these books leave you a little cold in the end—a bit as if you’ve spent the whole evening being entertained by the life of the party but you haven’t been asked to say much, and you still don’t know the guy’s name but you’re not sure you want to, and it’s time to go home.”

Who they are wearing

Queen Elizabeth visited Amherst’s Folger Shakespeare Library in 1991.

|

[1996] Sarah Auerbach ’96 writes an exposé on student fashion, revealing that, according to a college post office supervisor, most students receive the J.Crew catalog. Denials abound, with Adam Gregerman ’96—wearing a fleece-lined Land’s End shell jacket—insisting “that it’s a skewed statistic.” Professor of Anthropology Deborah Gewertz says that, when first at Amherst, “I felt obliged to buy an entirely new wardrobe of tweed jackets. I woke up every morning feeling that I wished I could turn into a 54-year-old white Anglo-Saxon male religion professor. One of the nice things about Amherst College is that it has become a far more diverse place.”

David Foster Wallace’s interview by mail

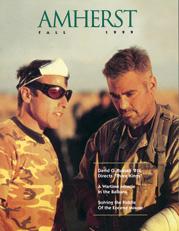

The chance to put George Clooney on the cover arose thanks to David O. Russell ’81E, whose movie Three Kings stars Clooney.

|

[1999] Amherst’s Stacey Schmeidel interviews David Foster Wallace ’85 by mail. Asked, “What were your aspirations when you left Amherst? And what are they today?,” he responds: “The fact is that we’d need four pages of back-and-forth to nail down exactly what you mean by ‘aspirations’ before I could even start trying to answer you … and this try would not be pithy or brief or probably even very interesting to anybody else.”

History lessons:

The Jim Ostendarp era ends in 1992, when the beloved football coach retires from Amherst after 33 years.

The gene for a bovine enzyme is cloned in the lab of Professor Patrick Williamson in 1996.

2000s

Bohjalian and Oprah

The magazine covered a 2007 speech by actor Jeffrey Wright ’87.

|

[2000] “When a writer is blessed by Oprah Winfrey, it’s a mixed blessing,” writes Professor William H. Pritchard ’53 in a review. “The good part is heavily increased book sales, and when Chris Bohjalian [’82]’s novel Midwives (1998) was picked by La Winfrey’s book club, his next one (The Law of Similars, 1999), had a first printing of 50,000, which is getting up there. The bad part—and maybe it’s not so bad for someone laughing all the way to the bank—is that Serious Literary Critics like yours truly will turn off instantly, assuming that anything Oprah likes must exist at a level of easy-access vulgarity that should be condescended to. So it is important to say that Mr. Bohjalian ... has produced over the last few years four books that constitute a solid, intelligent, and extremely entertaining fictional achievement.”

“The emotion was overwhelming”

[2001] Three alumni—Frederick C. Rimmele III ’90, Brock Safronoff ’97 and Maurita Tam ’01—are killed in the 9/11 attacks. After seeing the second plane hit the World Trade Center, Paul Rieckhoff ’98 puts on his National Guard uniform and arrives at Ground Zero. “The outpouring of civilian support was enormous; the emotion was overwhelming,” Rieckhoff tells the magazine. There was “just a deeper look in everyone’s eyes—a little more respect, a little more honesty.”

Scalia and the Constitution

|

[2004] In Johnson Chapel, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia P’02 describes the Constitution as “a rock with unchanging meaning,” not “a living organism” to be interpreted as one sees fit: “At the end of the road, the ‘living’ Constitution will lead to the destruction of the American Constitution. And you have seen the beginning of that.” Scalia’s lecture becomes “fodder for debate about appropriate forms of protest,” says the magazine, with some students who oppose his conservative opinions opting to “peacefully attend the lecture and distribute pamphlets outside the event. Two dozen protestors—mostly townspeople, including one in a duck costume” assemble on the Main Quad. Sixteen faculty members protest by staying away.

After Iraq

Danielle Santiago Ramos ’13 was part of a 2011 feature on efforts to enroll low-income and international students.

|

[2004] In a long interview about his time in Iraq, U.S. Army Lt. Rieckhoff talks about his reasons for serving: “I felt like, as a platoon leader with 39 soldiers on the ground in Iraq, I could make more of a profound impact on the way the world viewed America, and on the war, than I could by sitting home and grinding my teeth and writing letters.” That year, Rieckhoff starts the advocacy group Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, which, in 2011, has more than 180,000 members.

A Freakonomics mention

In 2009 a magazine photographer captured a small moment at commencement.

|

[2008] In a paper, Jessica Wolpaw Reyes ’94, assistant professor of economics, credits the Clean Air Act’s removal of lead from gasoline in the 1970s with a more than 50 percent decline in violent crime in the 1990s. Freakonomics author Steven D. Levitt blogs that Reyes “has put together what appears to me to be the most persuasive evidence to date in favor of a relationship between lead and crime.”

All photos are from Amherst magazine or Amherst College Archives and Special Collections.