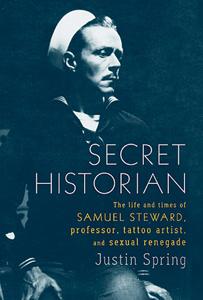

Secret Historian: The Life and Times of Samuel Steward, Professor, Tattoo Artist, and Sexual Renegade, by Justin Spring ’84 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Reviewed by Robert E. Weir

|

[Nonfiction] When basketball legend Wilt Chamberlain declared he had slept with 20,000 women, most observers dismissed his assertion as improbable braggadocio. His gay counterpart, Samuel Steward (1909–93), claimed a more modest 4,647 sexual encounters. Modesty was neither man’s strong suit, but unlike Chamberlain, Steward meticulously documented each of his conquests in a private “stud file” that recorded names, places and graphic details. In many instances there was also photographic evidence.

Most know Chamberlain’s name, but few have heard of Steward, whose life Justin Spring lays bare for the first time in Secret Historian, which was a 2010 National Book Award finalist. Were he alive today, Steward would probably chair a university’s queer studies department, but for most of his days Steward’s sexual behavior was not only considered immoral and psychologically perverse, it was also illegal.

As Spring notes in a skillful afterword that offers insight into the craft of research, Steward’s papers have been “kept under close guard” by the repositories that held parts of them: the Kinsey Institute, Yale’s Beinecke Library, Brown University’s John Hay Collection and Boston University. Why all the secrecy for a man who was a major contributor to Alfred Kinsey’s studies of male sexuality, and who lived 14 years beyond the 1969 Stonewall uprising that launched the modern gay liberation movement? Why is it that no one before Spring assembled the myriad pieces of Steward’s life?

The reasons for secrecy go beyond American society’s reluctance to discuss human sexuality. Protecting some of the famous names in Steward’s stud file played a big part: Rudolph Valentino, whose homosexuality was carefully hidden for decades; Thornton Wilder, who remained closeted; Alfred Lord Douglas, whose earlier relations with Oscar Wilde sent the latter to jail; and hundreds of U.S. military personnel. There is also the matter of Steward’s voracious and unsettling sexual appetite, one that extended to sadomasochism, bondage and relations with minors. (Many passages and photos in Spring’s book are decidedly NC-17.)

The tale also lay untold because Steward’s story is so complex. Most gay men at the time led a double life, but Steward assumed multiple identities. For 20 years after obtaining a Ph.D. in literature from Ohio State, he was Professor Steward to students at Carroll College, Washington State, Loyola University of Chicago and DePaul University, while he was also writing about homosexual life, under various pseudonyms, for gay-themed publishers. To dear friends in Europe, especially Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, he was Sammy Steward, an openly gay bon vivant bohemian. Well before he was outed as homosexual in 1956 and dismissed from DePaul, Steward was also “Phil Sparrow,” who operated a tattoo parlor near Chicago’s Great Lakes Naval Base. In the 1960s he wrote explicit gay pulp fiction under the name “Phil Andros.”

Although Secret Historian is carefully documented at every step, Spring tells Steward’s tale with the panache of a private detective turned novelist. It is credit to his prowess as a writer that this book is a page-turner, as much of what Spring discusses is difficult to digest. Steward is not always a sympathetic character; he could be vain and narcissistic at one moment, whiny and depressed the next.

And it’s certainly not an uplifting biography. Steward knew the cost of living as a gay man in an unaccepting society. He paid it because he could not do otherwise, but his life was often difficult, dangerous and unhappy. He formed few lasting relationships because his promiscuity knew no bounds. Particularly sad were his final years as an elderly and unattractive man operating a tattoo parlor in a ravaged section of Oakland, Calif., frequented by Hell’s Angels and routinely robbed by Black Panthers.

Good books take us to places we have not ventured on our own, and this is a very good book indeed. Reading Secret Historian casts us into bygone worlds, whirls us around fascinating social circles and confronts us full-face with social realities that many would be more comfortable not encountering. But, as Spring reminds us, denying our past doesn’t make it any less real.

Weir, a visiting professor of history at UMass, is a frequent contributor to the magazine’s Amherst Creates section.