Major (League) Overhaul

Neal Huntington’s challenge ("Major [League] Overhaul," Fall 2010) reminds me of the challenge facing Chicago Cub general managers for over 100 years. In fact, one of them is reported to have said: “We can’t win at home and we can’t win on the road. I just wish I could figure out somewhere else to play.” Good luck, Neal. We’re rooting for you.

Rich Lundgren ’80

San Diego

As a former Amherst baseball player, I read with special interest about the challenges faced by Neal Huntington ’91. As I read the article, I fully expected there would be mention of another Amherst-Pirate connection. No such luck; perhaps it was Old News.

From 1946 to 1985 the Pittsburgh Pirates were owned by John Galbreath, of Columbus, Ohio, with, for a time, Bing Crosby. The Amherst connection was Mr. Galbreath’s son Danny, Class of ’50, for whom the team locker rooms at Pratt Field are named.

A further baseball note: Harry Dalton ’50, a close friend of Danny’s, served as general manager of the Baltimore Orioles, California Angels and Milwaukee Brewers.

I know there have been many more Amherst men who have made names playing, coaching or managing baseball, but I thought it was timely to call attention to Danny and Harry near the 60th anniversary of their Amherst graduation.

John Williams McGrath ’51

Honolulu

Selectivity not an end in itself

I was surprised when I read the tribute to President Tony Marx in Amherst (“The Newest Alumnus,” Fall 2010). We are told that President Marx’s tenure has focused on “striving to make Amherst both the most selective and the most diverse liberal arts college in the country.” A few sentences later we are advised that Amherst’s selectivity has been “driven up” because of an increase in the number of applications.

While I certainly understand the desirability of making Amherst diverse, I don’t see the virtue of making Amherst the most selective college. Selectivity may result from attempting to recruit a diverse, curious and creative group of students. It is certainly not an end in itself. I would expect that President Marx would describe his achievements otherwise.

Jeffrey Metzger ’72

Vienna, Va.

|

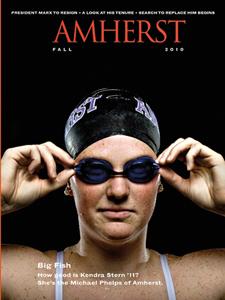

Big fish

I enjoyed the story “Big Fish,” by Justin Long, about Kendra Stern ’11 (Fall 2010). Swimmers like Kendra work so hard to achieve these fantastic times, and I’m delighted you took the time to recognize her accomplishments! Her steadfast interest in art history and her commitment to Amherst are admirable. While she is part of a larger team, I’m glad Long recognized the immense individual commitment it takes her to achieve so much for the team.

Beatriz Wallace ’04

Columbia, Mo.

Sculpture destruction—two views

Yesterday (Dec. 1, 2010), a man in New Haven bludgeoned another man to death using a baseball bat. This reminded me of how disappointed I was to read the account of the bat-wielding sculpture decimation (“Creative destruction,” College Row, Fall 2010) produced at Kirby Theater this fall. My main problem with it is the emptiness of purpose of the wanton violent destruction of sculpted likenesses of the head of a living being (one of Amherst’s finest professors, no less), particularly since there was no meaning or context to it. Isn’t there already too much real violence on this earth to deter sensitive human beings from creating more random images of violence, even if they are on stage? Can’t the Amherst drama department faculty think of anything more positive to create than this empty nefarious exercise? There is, of course, a place for the depiction of violence in the theater in places that fit into a story with a real message. In my humble opinion, this head sculpture decimation has no message, except that those producing it were insensitive and bankrupt for better ideas.

One wonders what was behind the urge of those responsible for this event to produce it. Although Amherst is endowed with a faculty and student body that are among the brightest and most scholarly of those on any campus, perhaps this episode suggests that there is room for improvement in terms of an atmosphere for developing a moral compass? Alternatively, perhaps the sculpture destruction is the work of the ghost of Chief Pontiac, whose Indian tribesmen were allegedly infected with smallpox under Lord Jeffery Amherst’s orders.

I salute and cheer for the vast majority of what goes on at Amherst today as in the past. However, I think that the head-sculpture-bashing episode was a bad mistake. Reading about it was a sad day for my feelings about my beloved alma mater.

K. Brooks Low ’58

Guilford, Conn.

I took sculpture from Mark Oxman in 1971. One of his methods of teaching involved us not getting too attached to our “art.” After an afternoon of frantic exhortations to “make art!,” Professor Oxman would ask us each if we had taken our sculpture as far as we could. If the answer was yes, the next step was to destroy the “art” so we could move on to our next effort.

It didn’t surprise me in the least that it was Mark’s suggestion for the decimation and that it was his “art” that was destroyed. Bravo! To thine own self be true.

Steve Cousey ’72

Summit, N.J.

The legend of the stolen books

In the latest issue of Amherst, there was an article on books which, according to tradition, were taken from the Williams College library and brought to Amherst by Williams students planning to enter the new college here (“The Great Book Theft That Wasn’t,” Fall 2010). Up to now, it stated, no evidence has been found that this actually happened.

There is another possible origin for the legend. In the 19th century many colleges and universities had debating societies, sometimes called literary societies. At Phillips Exeter Academy, which I attended, two such societies have been active since 1830.

It is possible that such a society existed at Williams and that it amassed a small collection of reference books which was taken to Amherst.

Perhaps the archivists of the two colleges could pursue this speculation.

Frank C. Whitmore Jr. ’38

Silver Spring, Md.

The Phi Psi Affair: “Unfraternal Conduct”

The obituary for Thomas Gibbs ’51 (In Memory, Fall 2010) contains only a brief allusion to an important event in Amherst history, an event in which Gibbs played the central role. In the spring of 1948 the undergraduate members of Phi Kappa Psi, the Amherst chapter of a national fraternity, issued an invitation to Tom Gibbs, a black freshman, to join the fraternity. Although Phi Kappa Psi was not one of the five Amherst fraternities that at that time still had exclusionary rules, the leaders of the national organization did not react favorably when they learned of the Amherst chapter’s intentions. After some not-so-cordial negotiations during the following summer and fall, the Amherst students notified the national organization of Phi Kappa Psi that they were determined to proceed with Gibbs’ initiation. At that point the national organization suspended the Amherst chapter, which reorganized as Phi Alpha Psi, a local fraternity. Three weeks later Gibbs, together with the other sophomore pledges, was formally initiated into Phi Alpha Psi.

Although it now seems hard to believe that an invitation to a black student to join an Amherst fraternity could cause such a furor, the “Phi Psi Affair” was national news. In The New York Times alone that fall there appeared at least six news items on the topic and an editorial, which read in part: “The Amherst College football team beat Williams on Saturday by a score of 13 to 7, but it may be that another sort of victory, won on the Amherst campus on Friday, will be longer remembered. Until Friday, Amherst had a chapter of the national Phi Kappa Psi fraternity. On Friday that chapter was suspended by the national executive committee for ‘unfraternal conduct.’... In this episode we see the real meaning of a liberal education. An Amherst degree has always been respected. It will be more respected now.”

Robert H. Romer ’52

Amherst

Re. the Hubert-Longsworth letter

Dick Hubert ’60 and Robert S. Longsworth ’99 provide a novel twist on the familiar claim that there is a menacing “imbalance” toward the left within America’s leading college and university faculty (“Is Amherst’s environment self-sustaining?,” Letters, Fall 2010).

Forty years ago, soon-to-be Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell said this imbalance was the most fundamental problem facing defenders of the free enterprise system. Now Hubert and Longsworth turn things around and tell us that, given Amherst’s “ongoing need for new capital and major alumni donations,” the college’s current left-leaning administration and faculty have created an educational environment that may not be self-sustaining.

We’re skeptical that there’s much (if any) risk that the college is or will be “against encouraging free enterprise on campus.” But we’re all for debate, and suggest it might begin by considering the journalist Joe Queenan’s account of how the American free enterprise system works: “Leftist academics get to try out their stupid ideas on impressionable youths between 17 and 21 who don’t have any money or power. The right gets to try out its ideas on North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Australia and parts of Africa, most of which take MasterCard. The left gets Harvard, Oberlin, Twyla Tharp’s dance company and Madison, Wis. The right gets NASDAQ, Boeing, General Motors, Apple, McDonnell Douglas, Washington, D.C., Citicorp, Texas, Coca-Cola, General Electric, Japan and outer space.”

We wonder if Hubert and Longsworth are aware that this basic deal has been struck, and what they think it might tell us about the future of Amherst.

Richard F. Teichgraeber III ’71

New Orleans

Charles S. Sims ’71

New York City

Hubert and Longsworth ask if the college’s environment is self-sustaining and laud “free-market capitalism” as the system that supports it. I have misgivings about that system, the directions it has been pushed into by its loudest advocates and Amherst’s dependence on enormous donations from a tiny number of alumni.

We first should ask if industrial capitalism itself is self-sustaining. Much evidence suggests that it is not. Its logic is growth and profit, but while its benefits are privatized, many of its costs are socialized, as its pursuit of growth forces costly externalities on the public: pollution, wasted resources, fouled landscapes. It is the driving force behind global warming and the environmental degradation so visible in developing nations. Historically, “scrupulous, well-managed capitalism” has been an oxymoron, until and unless governments imposed regulations and restraints. Invariably these are fiercely opposed by free-market capitalists, as they have been even after the market’s latest excesses (which lost Amherst one-quarter of its endowment) required massive public bailouts that left crushing levels of public debt. If capitalism deserves credit for its powers of accumulation and philanthropy, then it must accept responsibility for the serious harms caused by its inherent flaws, for its frequent crashes and for the government bailouts necessary to revive it.

Given its narrow vision and disregard for the future, capitalism has been able to create great wealth. But capitalism is agnostic regarding how that wealth is distributed. Other systems, including those of Western Europe, consider the distribution of wealth central to their definition of the good society. In the U.S., however, since the Reagan era, the free-market ideology has been employed to benefit the wealthy. The widespread growth that was supposed to ignite as tax rates on the rich were slashed failed to occur. Instead, the national wealth has become so concentrated that the top 1 percent control over 40 percent of it and the bottom half own virtually nothing. Such disparities mock America’s ideals of fairness, have hollowed out the middle class dream and threaten our political stability.

Yet Hubert and Longsworth seem content to depend on just this inequitable and unsustainable concentration of wealth to support Amherst College—to be reliant on the capricious generosity of a handful of alumni who have acquired great riches. With such riches comes unusual private power. We should worry about the influence that attends such large donations. Better for Amherst to have federal scholarships and granting agencies better funded through taxes and have wealth less concentrated, so each of our 20,000 living alumni were readily able to donate $5,000, and parents would need less financial aid. Contrary to the writers’ assertion, sustaining Amherst most assuredly involves political questions, about our natural environment, social justice and the college’s continued independence as an institution devoted to inquiry and teaching.

Stephen C. Murray ’66, P ’02

Goleta, Calif.

While I am one of the liberal-leaning left decried by Dick Hubert and Rob Longsworth, I support their suggestion for examining the institution.

Rather than a debate about free-market capitalism, I would suggest a more specific inquiry. It is understandable that I lost about 25 percent of my retirement funds in the recent financial breakdown, because I took only Economics 201 and have little knowledge or experience in the management and investment of money. It is curious to me that Amherst College, protected by a Board of Trustees and a finance committee, and with access to faculty, students, alumni and other well qualified advisers, should have done no better than me.

I suggest that an investigation of why our system did not protect our endowment would be an interesting academic undertaking that would also be of practical value in preventing such a loss from happening again. It could perhaps become a continuing course or a new branch of the study of economics.

I am also concerned about the breakdown of our governmental safeguards, but I am beginning to think that private interests will always find ways around and through protective laws, regulations and agency supervision. Therefore, if we could concentrate on our own institution, we might discover self-protective action that would be useful to other institutions as well.

I join in congratulating ourselves for our recovery. I am not accusing anyone of anything, but I suggest that we find the cause of the problem as a first step in finding a solution, and at the same time to educate ourselves.

Sam Liberman ’56

Sacramento, Calif.

Messrs. Hubert and Longworth’s letter adds a new twist to the periodic outcries from the right that Amherst and similar alleged hotbeds of academic liberalism must be made to see the light. The writers suggest that absent an institutional right turn, Amherst will suffer a significant loss of financial support: Contributors who have accumulated personal wealth through free-market capitalism will take their bat and ball and go home.

I question whether the facts warrant the writers’ concern. Does the college graduate less than its fair share of free-market enthusiasts? Is the philanthropy that is so important to the college dependent upon donors’ assessment of the attitude on campus toward free-market capitalism as distinguished from other views as to what’s best for the economic well-being of the nation? Is there a slant to the left that colors an Amherst education to the extent that well-heeled contributors will transfer their support to politically more conservative institutions?

Also worth asking: What consideration should be given in weighing a curriculum or related change to its impact on preserving the generosity of donors on one end or the other of the political spectrum? Should the content of an Amherst education be shaped to accommodate the political views of large contributors? How much is the money worth?

Last question: Must we really rephrase that old cheer: “Lean to the left! Lean to the right! Stand up! Sit down! Lean to the right!”

Benjamin W. Boley ’56

Washington, D.C.

|

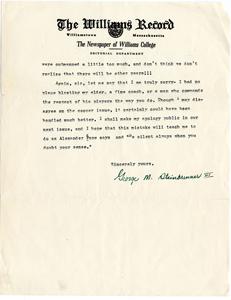

George Steinbrenner on Amherst football

The death of George Steinbrenner in 2010 reminded me of an incident almost 60 years ago which demonstrated the “hard and soft sides” of this remarkable Williams alumnus.

In 1951 I was the captain of the Amherst football team, a most unsuccessful one, which, in the second year of John McLaughry’s tenure as football coach, had a 2-5-1 record and lost to Williams 40-6.

With approximately two weeks left in the season, The Amherst Student reported that there was enthusiasm for the restoration of an old tradition, a bonfire, to inspire the football and soccer teams to victory against their opponent to the west. McLaughry publicly objected to the soccer team being included in these festivities, remarking, “There is only one fall sport at Amherst: football.”

At that time Steinbrenner was a senior at Williams and on the football team, although he rarely played. He was also the sports editor of the Williams student newspaper. Before the game with Amherst he wrote a rather scathing column excoriating McLaughry for what he believed to be an insensitive position. When the game followed, it was a disaster for Amherst. Approximately a week later, Steinbrenner sent a four-page letter to McLaughry apologizing for his column, saying, in effect, “We beat you this year, but I fully expect you will retaliate in the future.” I came across this letter when I was presented with a scrapbook of the 1951 season, assembled by McLaughry’s former wife, which I later returned to the college.

Three years ago I wrote Steinbrenner at his Yankee Stadium address, reminding him of this incident. He never responded.

James B. Lyon ’52

West Hartford, Conn.

Editor’s note: In this issue of Amherst magazine, we are proud to unveil a new personal-essay department. Called

Insights, the section will give alumni writers the opportunity to reflect on a particular topic of interest to our readers. We will publish four Insights columns each year, and while we welcome submissions, we ask that you first contact us at magazine@amherst.edu for specific submission guidelines. In the inaugural Insights column, Eric Patterson ’70 writes about his struggles as a gay student on a campus where “aversion therapy” was endorsed as a “cure” for homosexuality. Please read the essay and let us know what you think.

We welcome letters from our readers.

Send them to:

Amherst Magazine

Office of Public Affairs

P.O. Box 5000

Amherst, MA 01002

Or e-mail them to eboutilier@amherst.edu.

George Steinbrenner's letter to The Williams Record courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections