104

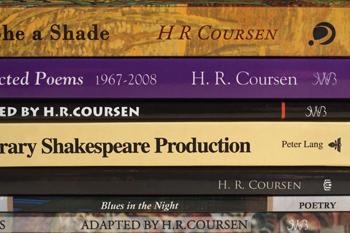

Incredibly, that’s the number of books that Herb Coursen ’54—who died in 2011—wrote and got published during his lifetime.

By Roger M. Williams ’56

|

[Writer’s life] I’ll bet that nobody you’re aware of has generated more books than Herb Coursen did: He was working on number 105 at the time of his death, on Dec. 3, 2011. Foremost among these books were 35 novels, 33 collections of poems, five adaptations of Euripides’ plays, four anthologies of student writing, translations from French and Spanish and, oh yes, 16 studies of Shakespeare’s body of work. Along the way, Coursen became something of a minor-league John Updike, roaming all across the literary map.

Few of Coursen’s books found a major publisher. In our interview last fall at his home in Brunswick, Maine, he professed not to care, not only because he had a dependable income but also because, “for me, writing is a thoroughly enjoyable activity, without regard to what others say about the results. The writer works to please himself.”

Nearly as impressive as Coursen’s literary output is the fact that he produced it on top of a full-time college teaching career. He taught English at Bowdoin College from 1964 to 1991. Then, not content to retire to his keyboard, he became a visiting professor at a long string of other schools, director or codirector of numerous seminars and a lecturer at so many institutions that their names ran side by side across 11 lines of his résumé. He gained such renown in the Shakespeare field that Penn State, in 1996, named him one of 25 “master teachers” of the Bard in the past 100 years in the U.S., Canada and Great Britain.

His attraction to Shakespeare began in high school and, curiously, connected to sports. Coursen recalled during our interview: “During senior year, after football practice, stiff and sore, I’d read Hamlet. It fascinated me. Then I saw Olivier play the lead role in the movie version. I realized that Shakespeare’s greatness lay not just in putting wonderful words on a page but also in creating an entire world around them.”

Coursen wrote his books in a plain-looking, intriguingly cluttered house in the Maine woods. The walls sagged with memorabilia, ranging, in his office, from old sports photos to posters of Shakespearean productions to snapshots of his grandchildren and his late companion, Pamela. “I stare at them for inspiration,” he said. “I try to write something I like every day—even in a notebook while traveling—and go to sleep better when I do: a cure for ‘writer’s block.’ When I stop, I always know what my next paragraph will be when I start again.”

Personal experiences often drove his fiction, much of which he set on a college campus. His novel The Outfielder could be called wishfully autobiographical. It tells a story, and to an impressive degree the story, of major-league baseball during World War II. The draft decimated many teams, including the formidable New York Yankees. Coursen’s protagonist, a Princeton grad named “Bucky” Rogers, wants to enlist in the service but can’t because of a football injury. He starts playing minor-league baseball and winds up a Yankees outfielder.

If that premise requires some suspension of disbelief, nothing else in the novel does. Drawing on his deep knowledge of the subject, Coursen populated the story with real players and their real strengths and weaknesses. California’s little-known Heidelberg Graphics published The Outfielder as well as numerous other Coursen titles.

Among all his books, Coursen cited only As Up They Grew, a collection of autobiographical essays, as an appreciable moneymaker: “I got a royalty check that paid for a trip to England to attend a Shakespeare conference.”

Pressed on the matter of writing so much for little financial gain, Coursen invoked a hallowed Amherst name: Robert Frost. “Until the last 10 years of his life, Frost didn’t make money from his poetry. For many years [including Coursen’s as a student], the college gave him a stipend every spring to deliver lectures and let him be a writer.”

Pretty decent footsteps to follow.

Williams is a writer in Washington, D.C.

Photo by Rob Mattson