By Katherine Duke ’05

|

Last year, a 2-year-old in Foshan, China, wandered into the road, where vehicles repeatedly struck her, and for a full 10 minutes, not one of many passersby stopped to help; she died of her injuries a week later.

In Guyana in 1978, hundreds of members of the “Jonestown Cult” fatally poisoned themselves and their children at the urging of leader Jim Jones.

In the 1930s and 1940s, more than 23,000 non-Jews in at least 45 countries risked their lives to aid, hide and protect Jewish people, even as the Nazis were committing systematic mass murder.

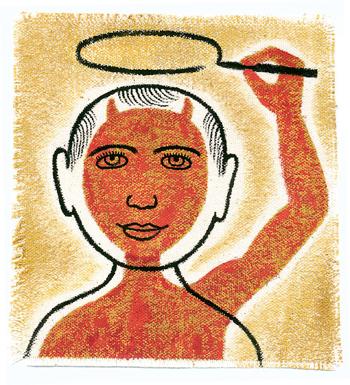

What explains these kinds of events? What drives human beings to be so horrifically cruel and callous to one

another—or so heroically helpful and generous? Professor of Psychology Catherine Sanderson shed some light on these questions in her new interterm course, “The Psychology of Good & Evil.”

Among the many studies the class considered was the infamous Milgram Experiment, which showed that ordinary people are often willing to inflict pain on others (in this case, increasingly severe electrical shocks) if authority figures instruct them to. Before Stanley Milgram designed and carried out the study in the 1960s, the prevailing assumption “was that there are evil and bad people, and evil and bad people behave evilly, and other people do not,” Sanderson told the students. “[But] what seems to be the case is that it’s not really the person and who they are; it’s really about the situation—which means that all of us, or most of us, in this situation could behave in a way that probably would not make us proud.”

“The Psychology of Good & Evil” attracted some 50 students—about twice as many as Sanderson had planned for—in part because of her reputation and teaching style. “Professor Sanderson proved to be exactly the superb professor that all of the students here at Amherst say she is,” says Morgan Brown ’15, who appreciated the professor’s “frequent and hilarious relevant personal anecdotes” (such as the one in which Sanderson confessed to responding with “a gesture that was not a wave” to an inconsiderate motorist in front of her at a fast-food drive-through).

“Sanderson will make even the most complex psychological theories easy to digest and memorable,” says Tracy Huang ’11, a law student who returned to Amherst to take the course. Huang found especially useful Sanderson’s applied-psychology lesson on how to get help from a bystander in an emergency. (A tip: Pick out one particular person to ask for help—“You, ma’am, in the blue sweater!”—in order to avoid “diffusion of responsibility,” which is when everyone in a crowd assumes that it’s someone else’s job to take action.)

Sanderson is now working on a book on the psychology of good and evil, and she plans to develop the interterm course into a full-semester, for-credit course in the near future. Many students will agree: that’s good.

Image © 2012 James Steinberg c/o the Ispot.com