By William Sweet

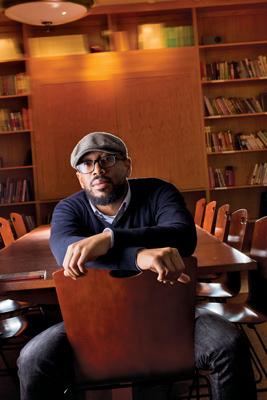

A self-described “military brat,” Khary Polk spent much of his childhood as an African-American living abroad. That experience, says the Robert E. Keiter 1957 Postdoctoral Fellow and visiting assistant professor of black studies, is helping to inform his current research on the role of black soldiers in the civil rights movement.

“The movement of black soldiers and black people in the United States has always been so surveilled and so restricted,” says Polk, who is now writing a book on the topic. (It was also the subject of his recent New York University doctoral dissertation.) While some portray the racial integration of the U.S. military as an outcome of the civil rights movement, Polk argues that the influence often went in the other direction.

“Even though many soldiers were still dealing with the prejudice of the U.S. military, being outside the boundary of the United States created a new sense of possibility that, I think, really changed the outlook of many African-Americans,” he says, ultimately resulting in improved rights for civilians and soldiers.

For example, lawyer Charles Hamilton Houston, a 1915 Amherst graduate, served in World War I and went on to mentor African-American jurists—such as U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall—who would join him in laying the legal groundwork for the 1954 Supreme Court decision that banned racial segregation in public schools. Another Amherst alumnus, William H. Hastie ’25, was instrumental in advocating for African-American soldiers in World War II.

Indeed, black soldiers affected the world both culturally (they introduced ragtime music to Europe) and politically: As Polk argues, interactions between American blacks and their counterparts in Africa played a role in the rise of the anti-colonial movement.

“Civil rights,” says Polk, “have had this hidden connection to the U.S. military for such a long time.”