By Katherine Duke ’05

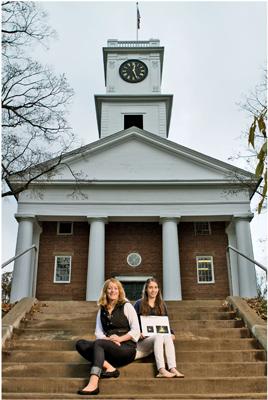

Iker (left) and Allyn

|

When Annemarie Iker ’12 and Katie Allyn ’12 enrolled in the English course “The 20th Century: 1900–1941,” they didn’t know it would lead them to publish their own book. They weren’t even familiar with the figure who would become the book’s subject.

“The biggest names that popped up when I thought of 20th-century American literature, before taking [the course], were probably Fitzgerald, Hemingway—you know: the big guys,” says Iker. The course, taught by Barry O’Connell, the James E. Ostendarp Professor of English, introduced her to new writers—including former Amherst lecturer Tillie Olsen.

O’Connell assigned the class to read Yonnondio: From the Thirties, Olsen’s unfinished novel about a poor American family in the pre-Depression era. The novel’s fragmented style, multiple narrative voices and attention to the often-overlooked experiences of women and children made it “so strikingly different from every other book I’ve read in any class,” says Allyn.

Olsen dropped out of high school, became a union organizer, raised four children, held fellowships at Stanford and Radcliffe and published her first book, 1961’s Tell Me a Riddle, before becoming one of the first women to join the Amherst faculty—where she was hardly a natural fit among colleagues with Ivy League degrees. And “Tillie Olsen wasn’t just a woman—she was a communist woman,” Iker points out. To the entirely male, predominantly white and mostly affluent student body, she offered courses on “The Struggle to Write” and “The Literature of Poverty, Oppression, Revolution and the Struggle for Freedom.”

Allyn and Iker were so intrigued by Olsen that, months after the course ended, they would stand out in the snow marveling over Yonnondio and fantasizing about doing a research project on her life and work. Last summer, they did just that.

With funding from the Office of the Dean of the Faculty, encouragement from O’Connell and advising from Assistant Professor of English Robert Hayashi, they read and re-read what Iker calls Olsen’s “slim but powerful oeuvre” (which also includes the nonfiction book Silences, about the circumstances that can prevent people—especially mothers and working-class people—from generating and publishing large amounts of writing).

They also flew to Northern California, where the author lived until her death in 2007, to delve into the Stanford Archives, which hold Olsen’s notes, manuscripts and syllabi. In addition, they interviewed (among others) former Amherst professor Leo Marx, who helped to recruit Olsen to the college; author Scott Turow ’70, who did an independent study with her; and Robin Dizard, Lorna Peterson and Marietta Pritchard, three “faculty wives” with whom Olsen socialized and participated in the women’s movement in Amherst.

The end result is Tillie Olsen and Amherst College: Conversations. The self-published book (available for purchase through Blurb.com) describes Amherst in the late 1960s and early 1970s, examines Olsen’s lasting impact and shows evidence of the popularity of her courses: “I’m taking this course (my first literature course ever),” reads a student’s handwritten note, “because of the nature of most lit. courses. Most represent the elitist culture of the time, not the mass culture, or working-class culture.”

This summer project was not for academic credit—just “life credit,” the students say.

Photo by Rob Mattson