Reviewed by Nicholas Mancusi ’10

Harlan Coben ’84’s latest novel is set at a fictional college that might sound familiar: it has a Johnson Chapel, a Valentine dining hall and a place in town that makes a killer popover.

[Fiction] Harlan Coben is a writer in the enviable position of not having to worry about negative reviews. His loyal readership snaps up his books (more than 20 novels, including the number one New York Times bestsellers Stay Close, Live Wire, Caught, Long Lost and Hold Tight) as fast as he can turn them out, and his shelf space in bookstores around the world is firmly cemented. Perhaps the clearest sign of marketplace success: on the dust jacket of his latest offering, Six Years, his name is twice as large as the title.

If all of this sounds like a throat-clearing prelude to a snobby pan, sorry to disappoint. Coben is great at what he does, and what he does is write thrillers (an outright slur in the more tweedy literary demimonde) that actually thrill. Six Years (Dutton) is no exception.

The book is narrated from the point of view of Jake Fisher, a professor of political science at a small fictional college called Lanford that readers of this magazine may recognize. (There is a Johnson Chapel, a Valentine dining hall and a place in town called Judie’s that makes a killer popover.) Six years prior to the narrative present, Jake sat in the back pew of a church and watched the love of his life, an artist named Natalie, marry another man. He swore to leave the bride and groom alone in their new life, but six years later, after he stumbles across the groom’s obituary, he decides to look her up. Easier said than done: nobody at the artist colony where Natalie and Jake met and spent most of their brief relationship seems to even remember Natalie’s existence, and the widow that the dead man left behind is someone else entirely.

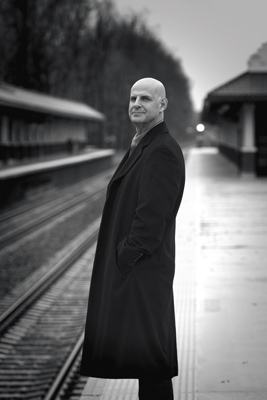

Coben’s utter lack of pretension is the reason his new novel works so well. Photo by Claudio Marinesco.

As Jake becomes more and more obsessed with finding Natalie, he is drawn into an increasingly complex plot involving bank robbers, the mafia, corrupt police and even some of the faculty of the unassuming college on the hill. Short chapters bear the plot along briskly through a series of well-earned twists and revelations toward a climactic shoot-out, and the book is definitely, as they say, hard to put down.

The reason it works so well is Coben’s utter lack of pretension. (Surely this sounds backhanded, but bear with me.) Capital-L Literary authors often gnash themselves to ribbons over their reluctance to write “entertaining” fiction, but Coben has no time for such self-flagellation. Jake Fisher is a figure of pure aspiration, a well-respected academic who is also 6-foot-5 and built like a linebacker, able with equal aplomb to deliver a lecture, flirt with a secretary and punch his way out of a moving van driven by armed assailants. He’s got problems, but they’re problems that can be solved with guile and force, and the reader wouldn’t mind having them as well, as long as they led to a similar adventure.

Compare this to the problems of some more literary characters: disenchantment with modern life, estranged relationship with mother, family dying from famine, etc. No thanks. Or at least, not while I’m at the beach. When an author tries to tell a fun, fast story and also make larger allegorical points about the human condition, it can be a disaster. Coben knows better.

This is not to suggest that his writing is subpar on a sentence-by-sentence level; Coben may not care much for descriptions of the moon or what it feels like to be romantically depressed (and thank goodness for that) but his action crackles with nary an adverb to be found, and his writing is largely devoid of the clichés that plague the genre (except for a single instance of the phrase “then it happened.”)

Are there formulas at work in Coben’s books? Yes, sure, perhaps more in structural elements and pacing than in plot. But what’s wrong with a good formula? Formulas are why a gun will fire, just about every time you pull the trigger.

Mancusi has a column on The Daily Beast and blogs at Galleyist.com. His writing has appeared in various other publications.