No Longer Neutral

By Joshua Kors ’01E

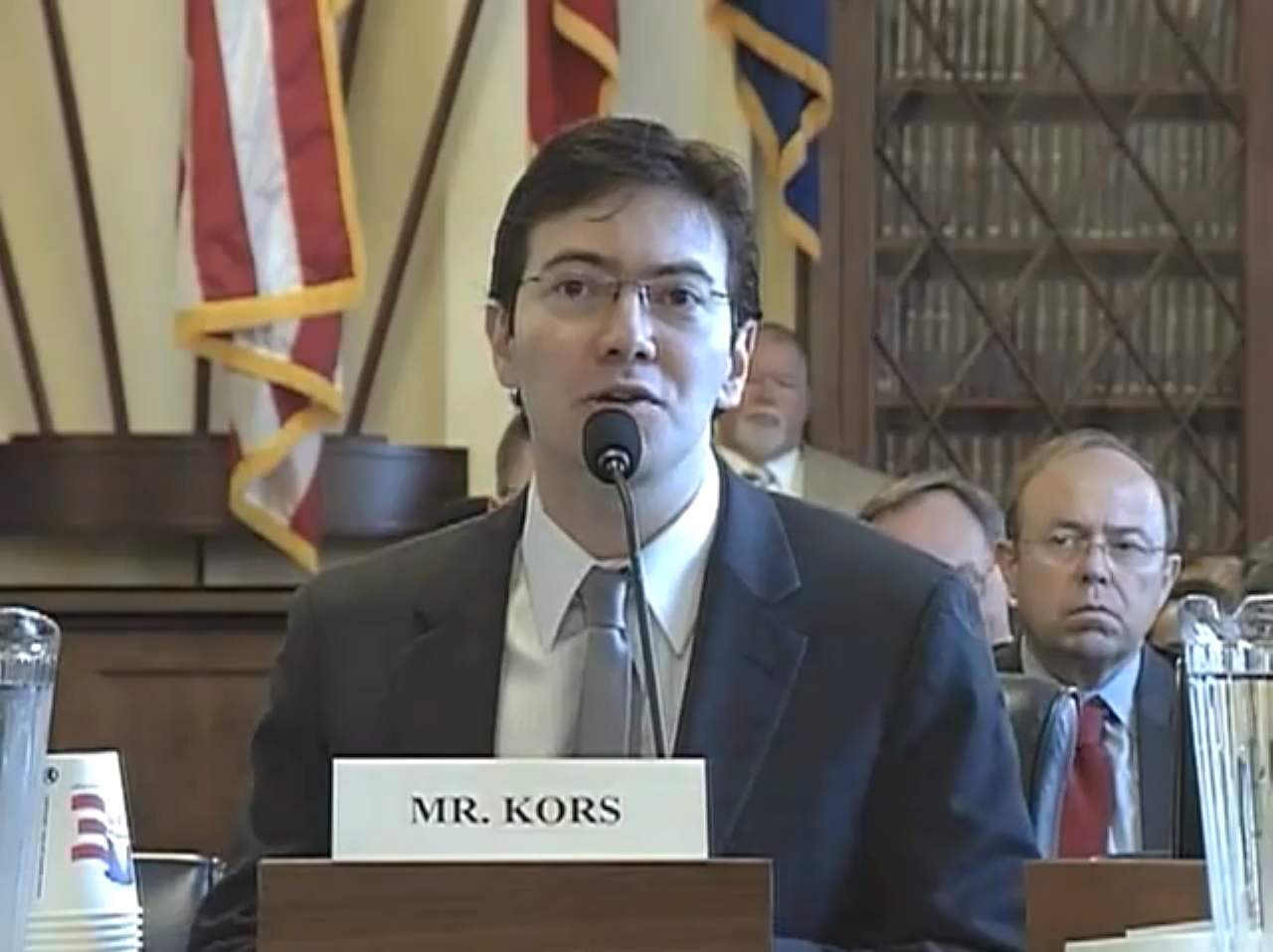

On my wall I keep a framed photo of Army Specialist Jon Town. He is out of uniform, wearing a gray suit and crimson tie, yet he is standing at attention, a look of determination in his eyes. The photo was taken in the halls of the U.S. Capitol on July 25, 2007, the day Town and I testified before the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs.

I’d met Town 10 months earlier, shortly after he returned home from Iraq. I had been volunteering for Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, producing a series of soldier profiles for the group’s website. The soldiers’ stories were extraordinary. One sergeant met his wife in Afghanistan; another ushered sick Iraqi children into Jordan for medical treatment. Town was supposed to be the fifth soldier in the series. His story struck me as deeply troubling.

Town had been serving in Ramadi, Iraq, when a 107-millimeter rocket exploded in the doorway two feet above his head, knocking him unconscious. The blast left him with severe hearing loss, and he was awarded the Purple Heart for his wounds. But when it came time to discharge him, Town’s doctor declared that he wasn’t wounded, that his deafness was caused by a pre-existing “personality disorder.”

Discharging him with that diagnosis, the Army prevented Town from collecting disability pay and receiving long-term medical care.

Joshua Kors '01E testifies before the House Committee on Veterans' Affairs.

Over the next 10 months I uncovered dozens of cases like Town’s. One soldier was punctured by grenade shrapnel in Iraq; his wounds were blamed on personality disorder. Another soldier developed an inflamed uterus during service. Her Army doctor linked her profuse vaginal bleeding to personality disorder. I examined medical and discharge records and spoke with officials who said a massive fraud was under way. More than 31,000 soldiers have been wrongfully discharged with this pre-existing condition, saving the military $17.2 billion in disability and medical benefits.

In April 2007 The Nation published my article “Thanks for Nothing: How Specialist Town Won a Purple Heart and Lost His Benefits.” It set off a firestorm. Town’s story was picked up by CNN, NPR, the BBC and Washington Post Radio. It was even dramatized on NBC’s Law & Order.

My life changed too. After graduating from Amherst, I’d spent six years writing insignificant fare for small-town papers: profiles of the local ice cream man, details of the new regulations for park bench dedications. In giving a voice to Town and the other soldiers, I had found my own.

For uncovering the personality disorder scandal, I won the National Magazine Award and was named a finalist for the American Bar Association’s Silver Gavel Award. ABC News’ Bob Woodruff and I collaborated on a Nightline piece about Town, part of a series that won the Peabody Award.

The public reaction was enormous. One wounded veteran began donating his disability benefits to Town’s family. Rock star Dave Matthews got involved, placing a petition on his website urging Congress to investigate. Within weeks, it had 23,000 signatures.

Three months later there I was, at the witness table in a packed room on Capitol Hill, sitting before the House VA Committee. As a swarm of photographers snapped photos, I took a deep breath, reached for the microphone and laid out the harrowing details I had uncovered. In addition to Town’s case, I described the struggles of soldier Chris Mosier, who was wounded in Iraq, then discharged with pre-existing personality disorder and denied benefits. Without adequate medical care, Mosier returned home to Iowa, then shot himself.

My words were met with stunned, sympathetic expressions. I had struck a chord, one that echoed quickly throughout the capitol. Barack Obama, then a senator, introduced a bill to halt all personality disorder discharges. Rep. Bob Filner introduced a matching bill in the House. President Bush signed a law requiring the Pentagon to investigate my reporting.

Encouraged, I pushed forward, eventually triggering a second Congressional hearing. As my investigation continued, I felt my identity as a neutral reporter beginning to evolve. Night after night I received phone calls from wounded soldiers desperate for assistance. As a neutral journalist, my obligation was to tell them, “Sorry, I’m just a reporter.” But I didn’t. First, I connected them with veterans’ advocates. When the requests became overwhelming, I created a list of resources for wounded vets and included it in my Huffington Post column.

One day it clicked: This is who I am. An advocate, not a reporter.

I look back at my opening statement during that first Congressional hearing and smile. In my closing moments, my voice tinged with emotion, I said, “As a journalist, it’s not my role to make any recommendations. But I do want to share with you the hopes of the wounded veterans I spoke to this year, which is a hope that someone be held responsible.” Turns out, to paraphrase President Obama, I was the someone I had been waiting for.

I turned to Amherst and was awarded the college’s Charles B. Rugg and C. Scott Porter ’19 Memorial Fellowships, financial support I am using to attend law school. This week I begin studying at Vanderbilt University. My reporting on wounded soldiers has led others to help them. Soon I will be able to step forward in a court of law and help them directly.

Joshua Kors '01E covers veterans' issues for The Nation and the Huffington Post. His website is www.joshuakors.com.