Love Letters on the Bathroom Wall

By Eric Goldscheider

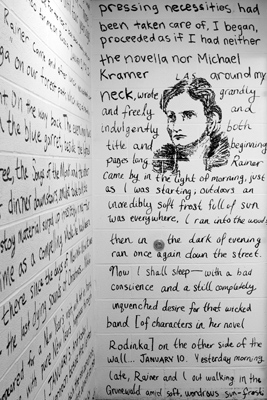

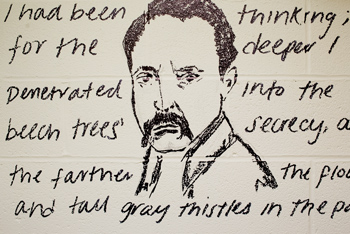

[Mischief] Late last semester, missives between two turn-of-the-20th-century European intellectuals mysteriously appeared on bathroom walls in Frost Library, just yards from the German literature stacks on B Level. Grout between the cinder blocks served as lines on a page for permanent-marker-wielding truants.

Technically, the passages—from the letters of Rainer Maria Rilke and the diary of Lou Andreas-Salomé—qualify as graffiti, as do drawings that accompany the words. But instead of ordering harsh chemicals to restore the walls to their off-white blankness, the library staff took a bright view of this fin-de-school-year expression of literary verve. “We admire the creativity and resourcefulness far more than we are troubled by the transgression,” says College Librarian Bryn Geffert. The words will be preserved.

But who should get the credit (or blame)? Professor of German Christian Rogowski offers context for understanding the responsible parties. When the bathroom artists struck, he and 15 students were finishing a course on Rilke, one of the most celebrated German poets of the 20th century. Not long before, President Biddy Martin spoke to his class. Martin wrote a book about Salomé, the psychoanalyst and intellectual powerhouse who was remembered mainly for the famous men she knew. “She was a friend of Nietzsche, a lover of Rilke and a student of Freud,” says Rogowski. “Biddy was the first critic to put Salomé back on the map in her own right.”

In the passage in the women’s restroom, Rilke, still unknown in 1897, gushes to Salomé, an established (and married) writer. Their ensuing romance helped shape Rilke’s literary identity. The men’s room features Salomé’s reflections, from her diary four years later, about needing to break off from a man 15 years her junior. As Rogowski explains, “To be assigned the role of muse, mother, lover, therapist of this very demanding young man was getting a bit too much for her.”

Count Martin among those pleased with the graffiti. She even talked about it in this year’s commencement address: “I never imagined ending up at a place where mischief takes the form of memorializing the love letters of late-19th-century intellectuals and poets on bathroom walls.”

In fact, it’s not the first time Amherst students have added literary touches to lavatories. In 1978, passages from James Joyce’s Ulysses showed up in a Johnson Chapel bathroom, where they remain today. And a women’s restroom in Chapin Hall is decorated with quotes from J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books.

When Rogowski heard about the Frost bathrooms, he went to examine them. His assessment: “It required meticulous planning—the quotes are carefully spread out, and they end at an appropriate moment. This should not be regarded as an act of vandalism, but as an homage to a life of the mind.”

In the men’s and women’s rooms, Rilke and Salomé:

- “[B]ut I took the path toward Ammerland and forgot everything I had been thinking; for the deeper I penetrated into the beech trees’ secrecy, and the farther the flowers and tall gray thistles in the pale meadows beckoned me with their waving, the clearer it became to me: all this is a festival. There was nothing of the everyday up here; only the few times we had walked alone, up above, our souls silent and oh so close, had it been like this.”

- “I began, proceeded as if I had neither the novella nor Michael Kramer around my neck, wrote grandly and freely and indulgently. ... Rainer came by in the light of morning, just as I was starting; outdoors an incredibly soft frost full of sun was everywhere. I ran into the woods, then in the dark of evening ran once again down the street. Now I shall sleep—with a bad conscience and a still completely unquenched desire for that wicked band [of characters in her novel Rodinka] on the other side of the wall.”