By Michael Kelly

Fans of Mysteries at the Museum on the Travel Channel may have seen its recent piece on the Clarence Birdseye field journals, which are held in Archives & Special Collections at Amherst. The two-minute clip covered the basics, but there’s more to the story.

Clarence Birdseye arrived at Amherst in 1906, following in the footsteps of his father, Clarence Frank Birdseye, Class of 1874, and his older brother Kellogg, Class of 1902. As Mark Kurlansky writes in his book Birdseye: The Adventures of a Curious Man, Clarence developed a reputation at Amherst as an outsider. Already a dedicated naturalist, he spent much time in college roaming nearby fields and streams in search of interesting specimens. He also earned spare cash by trapping live rats and frogs to sell to research scientists and zoos.

That reputation is reflected in the 1910 Olio. The quote that accompanies Birdseye’s yearbook photo—“I ain’t afeer’d o’bugs, or toads, or worms, or snakes, or mice, or anything”—is a fabrication of the editors. The Olio makes reference to Birdseye’s absence after sophomore year, which came as a result of a reversal of the Birdseye family fortunes. No longer able to afford the cost of college, young Clarence never graduated.

The 13 manuscript volumes in the college’s Clarence Birdseye Journal Collection cover the period from November 1910 through July 1916. For most of that time, Birdseye was in Labrador, a sparsely populated frozen land known for abundant fish and game, including animals valued for their furs. Furs, not frozen food, were where Birdseye imagined he could make his fortune.

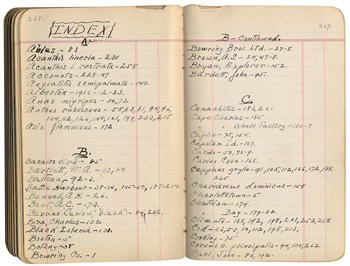

Although furs were his primary interest, his voracious curiosity about the natural world led him to record his observations on all sorts of flora and fauna, plus everything from dried trout to molasses pie. Birdseye was nothing if not methodical, and he passed the long, frozen evenings by preparing indexes to each of his field journals—a gift to researchers today. In September 1916, while living in Labrador, Clarence and his wife, Eleanor, had their first child, a boy they named Kellogg. The demands of new fatherhood may explain why Birdseye stopped keeping his field journals that year.

Birdseye’s observations in the frozen wastes of Labrador certainly influenced his thinking about food and freezing, but it would be nearly a decade before he turned those thoughts into a profitable technology. He spent most of the 1920s attempting to perfect a method of quick-freezing foods, starting with fish. His Aug. 12, 1930, U.S. patent—for a machine that freezes food into a block while retaining flavor—marks the beginning of the modern frozen food industry. By the 1950s, Birds Eye frozen foods had changed the way Americans eat their vegetables.

(Photo © Bettmann/CORBIS)

Kelly is the head of Archives & Special Collections at Frost Library.