By Stephen Hoffius

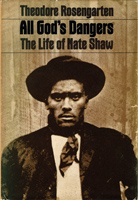

Forty years ago Theodore Rosengarten ’66 wrote an oral history of an Alabama tenant farmer. This summer it was a best-seller for the second time.

On April 18 The New York Times published the kind of rave review that any author would love, but especially if the book in question was first published 40 years earlier. It said that when customers at Square Books, the great independent bookstore in Oxford, Miss., come looking for the one book that best describes the South, the owner directs them to All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw, by Theodore Rosengarten ’66. The critic, Dwight Garner, seemed unfamiliar with the book, an oral history of an Alabama tenant farmer, though it had won a National Book Award when published in 1974. He found it, read it and proclaimed in the review, “[I]t is superb—both serious history and a serious pleasure, a story that reads as if Huddie Ledbetter spoke it while W. E. B. Du Bois took dictation.”

The next day the book soared to No. 1 on Amazon’s list of best-sellers. Several companies have since asked about the film rights. An audiobook will be released this year. All God’s Dangers is a hit. Again.

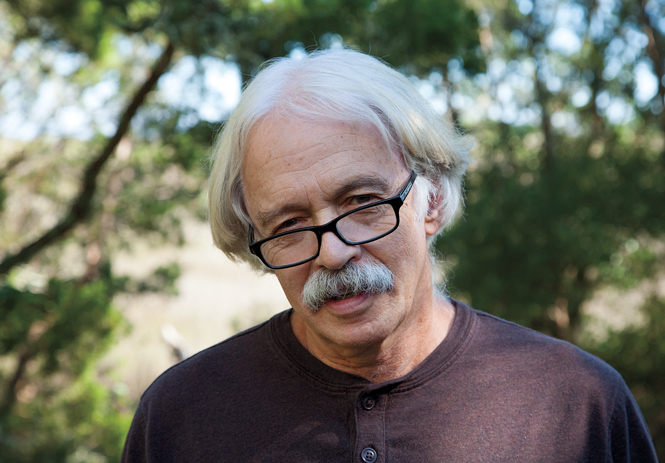

Rosengarten (above), who lives off a dirt road in a South Carolina fishing village north of Charleston, reports that the book has been in print continuously for four decades. Just like Garner, readers keep discovering it and are thrilled when they do. The author regularly receives phone calls and email from readers who claim that it perfectly describes their fathers—or grandfathers—black or white. All God’s Dangers has inspired oral historians around the globe for decades. James Earl Jones bought the film rights years ago but eventually gave them up. A one-man play starring Cleavon Little had a brief run off-Broadway.

All God’s Dangers is one of only two books Rosengarten has written in his 45-year career. But as he leans back in his home office, looking out over the marsh, he says, “I’m pleased with my productivity.” He’s talking not just about the books he’s published, but about his life.

Ted Rosengarten grew up Jewish in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn—a borough that has produced a surprising number of Southern historians—at a time when Eastern European refugees were moving into the neighborhood (and into his apartment building) and when Jackie Robinson was smashing barriers as well as base hits. “For me,” Rosengarten has written, “the narratives of black people and Jews in America were emerging simultaneously.” He adds, “I’ve never felt an artificial separation between black liberation and the struggles of Jewish people.” His career has been built on both.

In 1963, after a year at the University of Denver, Rosengarten transferred to Amherst. He loved hearing professors in American studies debate major issues: the Cherokee removal, the Vietnam War, civil rights. “It was a great method of teaching, and very inspiring, to know that nothing is really settled and carved in stone,” he says. “At Amherst you were taught a canon, but you were also taught to dissent.” He squeezed into crowded lecture halls to hear Leo Marx intone passages from Moby Dick and Huckleberry Finn. He heard William H. Pritchard ’53, in his early 30s, interpret T.S. Eliot, while poet Archibald MacLeish, then about 70, challenged Pritchard from the back row. He signed up for one of Ed Dolan’s classes on Homeric Greek, then came back for more.

Like many of his classmates, Rosengarten took part in the anti-Vietnam War demonstrations of the mid-’60s. When U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara was about to receive an honorary degree at commencement in 1966, Rosengarten was one of 19 students who walked out. “I had told my mother what was going to happen,” he remembers. “I didn’t tell my father. So my father poked my mother and asked, ‘Hannah, what’s he doing?’” The next day a photograph of the walkout appeared on the front page of The New York Times.

The following year, when he was called for the draft and went for his physical, Rosengarten undressed to reveal himself painted head to toe with a tapestry of anti-war slogans and symbols. A walking billboard, he was immediately dismissed. (A similar stunt a year later might have led to his deployment.)

Instead of heading to Vietnam, Rosengarten pursued graduate school at Harvard in a program called the history of American civilization (now American studies). Late in December 1968 he and his girlfriend, Dale Rosen, a Radcliffe undergraduate, traveled to Alabama to interview Ned Cobb, who had been active in the Alabama Sharecroppers Union in the 1930s. Rosen was writing her senior thesis on the organization. When the police went to foreclose on some of his neighbors, Cobb had confronted them and gotten into a shootout. He had served 12 years in prison.

Rosengarten and Rosen pulled up to the home where Cobb was living. He stood up as if he had been expecting them. As a child he had been told that after slavery Northern whites arrived in Alabama to help black people, and though they had left, they would return. They came back during the union drives in the 1930s. And now they were here again. “Hello, my children,” he greeted them. “I always recognize my people when I see them. Come on in. Come on in.”

The three sat down to chat, and Rosen asked Cobb why he had joined the union. “I was haulin a load of hay out of Apafalya one day,” he began. Eight hours later he completed his answer, by way of explaining the joys and sorrows of growing cotton as a black man in Alabama. Rosen and Rosengarten staggered away, overwhelmed by the bulk and beauty of his account. From this impromptu interview Rosen took the information she needed for that portion of her thesis. Rosengarten soon realized he “had found a black Homer, bursting with his black Odyssey,” as one reviewer would write.

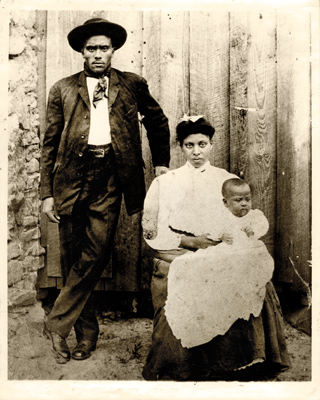

Right, Ned Cobb with wife Viola and son Andrew.

Two years later Rosengarten moved to Alabama, where he lived in a converted Pullman car. Several mornings a week he arrived at Cobb’s house with his tape recorder and sat on the porch or in the toolshed, asking questions. Cobb told him stories that may or may not have answered his queries. Each day Rosengarten played for Cobb the preceding day’s conversation. The old man scowled and retold the story, spinning it slightly differently. Rosengarten stayed for months. “I wanted to learn a way of thinking, something more private than information, more revealing,” he has written. “I was seeking their reflections, the stories they told themselves about themselves.”

Then slowly, painstakingly, he put it all together. He transcribed the interviews and, in those pre-personal-computer days, cut the pages apart and taped them back together. The floors of his apartment were carpeted with manuscript. Eventually he edited all the stories into a massive narrative, changing Ned Cobb’s name to Nate Shaw to protect Cobb and his family from recrimination.

Because the labor story was central to the book, Rosengarten took his manuscript to the left-wing publisher Pantheon, a division of Random House. Eventually the Pantheon editors proposed cutting out what they considered the extraneous stories—“all that stuff about mules and farming,” the very substance of Cobb’s life—and paring the manuscript down to the labor confrontations. Rosengarten refused. A Harvard mentor gave him the name of an editor at Alfred A. Knopf, a different division of Random House. Rosengarten picked up the manuscript from Pantheon and delivered it to Knopf, a few floors away.

Within a week he had a contract.

The book was like no other: a black farmer telling stories in colorful language about his struggles and triumphs, philosophizing, teaching. It begins, “My daddy had three brothers—Hubert, Bob, and Nate—and I’m named after one of em. Now, that Hubert, he was a over-average man.” One day Hubert went up to a white man’s house where he saw a dangerous-looking dog in the yard. He asked the white man to restrain the animal, and the man claimed the dog was “wired up, I fenced him.” But when Hubert opened the gate the dog immediately attacked him. “Uncle Hubert, he just jumped behind that white man, picked him up by his waist and commenced a slingin him at the dog, fightin the dog with the man. … Uncle Hubert just knocked that dog down goin and a comin until he knocked one of the white man’s shoes off… .”

As the praise piled up in 1975, the Harvard committee that oversaw doctorates in Rosengarten’s program changed its mind. Previously the members had turned down his proposal to record Ned Cobb’s life story as the basis for a dissertation. “There was some feeling that oral history belonged in sociology or anthropology,” he remembers, “and some suspicion against the tape recorder as a tool of a social-change agenda, except when the speakers were retired generals or corporate executives. But as soon as the book appeared—it all happened very quickly—the dean of the graduate school called me and said they would like to award me a Ph.D. for the work.”

So what does a young scholar who has produced a masterpiece at age 30 do for a follow up?

Well, Rosengarten and Rosen, who eventually married, moved to McClellanville, S.C., a town so small it is often omitted from maps. They felt as if they were living Edward Hoagland’s Notes from the Century Before—no stoplights, no coffee shop and a main street that ended at the town dock. They found some like-minded people, many but not all natives of the area. They rented a small frame house that they papered with National Geographic maps to keep the wind from blowing between the boards. And they dug into their new community in ways not unlike how Ned Cobb lived in Tallapoosa County, Ala.

They learned to fish and crab and shrimp. They grew a garden and baked bread. They shared stories with their new neighbors; they listened a lot.

In 1978 they bought 26 acres of bottomland on the edge of the Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge. They told themselves that if the persistent mosquitoes drove them away, as often seemed likely, at least the land would be a good investment. In 1980 they built a frame house with windows that overlooked the changing colors of the marsh; again, a good investment, not necessarily a permanent home.

They had a son, Rafael, in 1979, and another, Carlin, in 1984. They worked to establish a public elementary school with other parents and a remarkable school administrator, Juanita Middleton, who had moved back to McClellanville after more than a decade in New York City, with the goal of “revolutionizing education” in the community where she was born and raised. The Rosengarten boys were among the 10 percent of the school population that was white. The effort to establish a quality middle school in town took more years, and many contentious meetings with residents who balked at having a school that was mostly African-American in the heart of the village.

And they continued to do history work. At the South Carolina Historical Society, Rosengarten was introduced to the journal of Thomas B. Chaplin, an antebellum cotton planter from St. Helena Island near Beaufort, S.C. He transcribed and published it, along with a biography of Chaplin. Tombee: Portrait of a Cotton Planter (1986) won a National Book Critics Circle Award.

Tombee describes the desperate times around the American Civil War with a narrative as strong as if it were a novel. Rosengarten once said, “What I found distinctive about the journal was its picture of ordinary life—the naming of things and the ebb and flow of relationships, the diminution of experience by monotony and its elevation by passion. Great events loom behind the scenes, but in the visible world, people are eating, working, sleeping, falling ill and dying.” The cover of the first edition featured a wood-block illustration by Dale.

Rosengarten received a MacArthur Fellowship in 1989 and spent most of the money in no time, paying bills, buying a new boat (almost required for living in the area), and covering the costs of trailers for neighbors whose homes were destroyed when Hurricane Hugo flattened much of McClellanville in September of that year.

He taught for short stints at Duke, Harvard and the University of California, Irvine. He wrote speeches for the director of the National Endowment for the Humanities and published essays on a wide range of topics.

But a great deal of his work has had nothing to do with history. He founded two rural soccer clubs and coached in both of them. In the early years most of the players were African-American, from low-income homes. They needed instruction, but also shoes, uniforms, transportation and, often, encouragement and dreams. Rosengarten prodded them to finish high school and helped them find scholarships to enter college. He coached them for life, not just soccer. But they also played great soccer, often whipping opponents from Charleston’s lily-white suburbs.

Ted and Dale Rosengarten have often worked together on projects. One of Dale’s passions has been the local coiled baskets constructed of native sweetgrass, bulrush and pine needles, wrapped with strips of palmetto fronds. For centuries in South Carolina, lowcountry African-Americans have made these baskets in styles not unlike those made by their ancestors in Africa. They are among the most iconic art forms of the area. In 1986 Dale published an exhibition catalog, Row upon Row: Sea Grass Baskets of the South Carolina Lowcountry, then expanded her research on the connections between lowcountry baskets and those made in Africa. In 2008 she, Ted and colleague Enid Schildkrout published a monumental book on the subject, Grass Roots: African Origins of an American Art, which accompanied a traveling exhibit.

The couple have also combined research and writing on the subject of South Carolina Jewish heritage. Dale curated an exhibition and assembled an elegant catalog, A Portion of the People: Three Hundred Years of Southern Jewish Life (2002), which Ted edited and introduced. For 20 years Dale has built up a Jewish Heritage Collection for the Special Collections department of the College of Charleston library.

Ted Rosengarten too now concentrates on Jewish history. He teaches at the College of Charleston, where he holds the Zucker/Goldberg Chair in Holocaust Education, and at the Honors College at the University of South Carolina. Every other summer he and Dale lead student tours to Poland, Germany and other countries.

Just as he originally experienced Eastern European immigration to Brooklyn and Jackie Robinson at the same time, so he sees direct ties between the slavery under which Ned Cobb’s father lived and the concentration camps to which he takes his students. He has written, “I would say about Nazism what historian Frank Tannenbaum said about slavery in Slave and Citizen: The Negro in the Americas, published just after World War II: ‘Nothing escaped’ the influence of the Nazi program to kill the Jews, ‘Nothing and no one.’ Like slavery before it, Nazism ‘changed the form of the state, the nature of property, the system of law, the organization of labor, the role of the church as well as its character, the notions of justice, ethics, ideas of right and wrong.’ Nazi ideas, like slavery itself, ‘influenced the architecture, the clothing, the cooking, the politics, the literature, the morals of the entire group—white and black [Aryan and Jew], men and women, old and young.’”

Because of those connections, Rosengarten’s classes on the Holocaust are wide-ranging. He references African history. He describes slavery in America. “He’s the most moving speaker I’ve ever heard,” says one of his students, Catherine Mueller.

Rosengarten’s involvement with many of his students and student-athletes extends beyond the classroom and tours. He oversees senior theses and encourages career aspirations. He has helped edit the books and articles of students and friends, and even of strangers.

So when Rosengarten says he’s satisfied with his productivity, he’s not thinking just of the books he has added to bookshelves, but of the way he has worked with his community, friends, neighbors and students. As he walks around a classroom today, peering over his glasses, tossing out questions, his students often look to him the way he sat transfixed before Ned Cobb. They have found an openhearted, generous man who shares what he has learned from college classrooms, Alabama cotton fields and Nazi death camps. They have found a master storyteller.

Stephen Hoffius is a freelance writer and editor in Charleston, S.C.

John McWilliams photos