By William Sweet

How do our ideas about childhood inform our ideas about history?

[Research] It’s a culture often overlooked by scholars, though we have all at some point belonged to it: the culture of children.

For a book she’s writing, Professor Karen Sánchez-Eppler is delving into various archives to research children’s own accounts of their lives in the 19th century—an obvious strategy, she believes, but also a groundbreaking one.

“I feel a little bit like how it must have felt doing women’s history scholarship in the ’70s,” says Sánchez-Eppler, the L. Stanton Williams 1941 Professor of American Studies and English. In many of the same ways that histories of women and nonwhites have been given short shrift, she says, the lives and opinions of children are often devalued.

Her research is for a book on how our ideas about childhood inform our ideas about history. She first became interested in studying children in their own words as she worked on her 2005 book, Dependent States: The Child’s Part in Nineteenth-Century American Culture.

“My first book had been on abolitionist and feminist politics, and it would have never occurred to me that I could write a responsible book if I had only been using sources from white men,” she says. “But here I was writing a book about childhood in which I was only having sources from adults, and that seemed completely fine to me. I suddenly had this moment of ‘Oh my God—I never would have done this with my first project.’”

For her 2014–15 sabbatical year, she is doing research at Chicago’s Newberry Library, the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Del., and the Cotsen Children’s Library at Princeton University.

Imaginary World

The Mead Art Museum’s Pamela Russell likes to attend small-scale auctions for sport. In 2013 she won the bid on a shoebox full of what the auctioneer simply called “children’s doodles.”

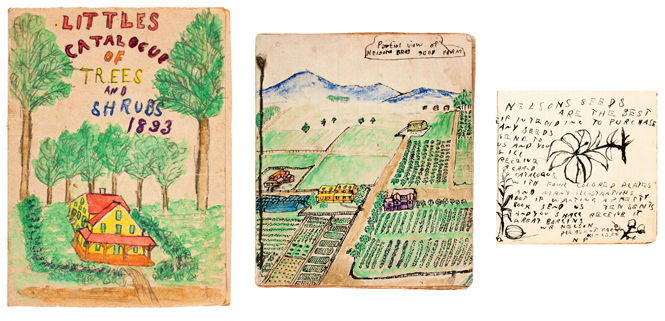

From left, a horticultural catalog from the boys’ imaginary world, their drawing of the family farm and an ad they created.

They were in fact the writings of two boys, Arthur and Elmer Nelson, who grew up in New Hampshire in the 1890s. These miniature books describe farm life through children’s eyes, and also include illustrated stories of imaginary lands and historical exploits.

Russell—the Mead’s interim director—showed the books to Professor Karen Sánchez-Eppler, who made them the subject of a Mellon Research Seminar last spring. The books are now in the college’s Archives and Special Collections, and they’re among the items that will inform Sánchez-Eppler’s research on children.