By Emily Gold Boutilier

It was like the hum of the old Dolby sound test, but instead of an electronic crescendo demanding her attention, it was her mother’s voice at a Christian Science independent-living facility in Boston.

“You know, you could just stay here,” her mother said. “My bed is big enough for both of us. Or we could put pillows on the floor.”

That’s when Jonatha Brooke put her next record, and her next tour, on hold.

By then Brooke had made 10 records during her fruitful career as a folk-rock singer-songwriter—roughly one every other year since her first in 1991. Her earliest were with Jennifer Kimball ’85, her partner in The Story, the group they started at Amherst. Her most recent album was 2008’s The Works, in which she set unpublished Woody Guthrie lyrics to music.

Now it was 2010. Brooke’s mother, Darren Stone Nelson, a poet, was in the middle stages of Alzheimer’s and in a home ill-equipped to care for her, although the staff was trying its best.

Usually, visits would end with Nelson telling her daughter, “You’re busy. Don’t worry about me; I’m fine.” She never wanted to be a burden. So when Nelson said, “You could just stay here,” her daughter knew: “That’s the cry and I’m going to answer it.”

Brooke realized, “I can give her what she needs, which is love. I can’t be impatient with her. This is not her fault. It was like everything else went away, and there were these two tiny voices—mine and my mother’s.” In that moment, her mother became the only thing that mattered.

Brooke lives in a spacious apartment on Fifth Avenue in Spanish Harlem, where the walls are painted in aqua, orange and red, and a semicircular diner booth sits off the kitchen. In addition to living there, she and her husband, Patrick Rains, who is also her manager, use their apartment as an office for their two record labels. When I visited on a late-spring afternoon, a staffer was working at a desk next to the living room. Behind her were stacks of Brooke’s CDs.

In September 2010, Brooke was supposed to make another record. “Instead,” she says, “I moved my mother in with me”—first into the back room of their apartment and then, about three weeks later, into a small apartment four floors down. With Rains and his sister Julie (and soon with others caregivers as well), Brooke joined the millions caring for loved ones with dementia.

“From the first minute,” she says, “it was clear that survival was in finding a creative way through it.”

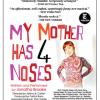

On Valentine’s Day in 2014, Brooke made her off-Broadway debut at The Duke on 42nd Street. It was opening night of her one-woman show, My Mother Has 4 Noses. The musical, which has 10 songs, documents the final two years of her mother’s life. It was Brooke’s first stint as a playwright, and as an actor.

The project began as a blog. As she cared for her mother, Brooke took notes and photos. “I started writing about it on my website—short stories about caring for my mom,” she says. “I’d keep them distilled, not maudlin, not too depressing. I’d try to find something redemptive about whatever happened that week. And people started really responding.” From an August 2011 entry:

She told my husband Patrick that she didn’t have any kids. But she calls me 10 or 15 times a day and knows exactly who I am. She told me that she will marry Patrick if I ever let him out of my sight. And, fickle as ever, just yesterday, she fell madly in love with Julie’s husband Jim, and proposed to him. So I guess it was a good weekend.

A month later Brooke wrote that Nelson was growing fearful of getting up each day.

Imagine everything that made sense yesterday being gibberish today. She is angry and lost. No map, no GPS, no guide. Sometimes the only thing that helps is holding her hand and staring deep into her eyes. “Are you REALLY Jonatha,” she’ll say. “Yes, mom, I’m really Jonatha.” More tears, “I’m so glad you’re here.”

Initially, Brooke thought the material might inspire her next record. “As I learned more and wrote more and got more responses from my fans,” she says, “it became clear there was something powerful about approaching Alzheimer’s artistically, talking about it through songs, through stories. Yes, some of them were harrowing, but there was great humor and great love at the root of everything.”

Even before Alzheimer’s, Nelson “would mine the daily dialogue for theatre,” Brooke writes in the liner notes to the My Mother Has 4 Noses CD (a companion to the musical). “Boolie!” Nelson would say, calling her daughter by a nickname. “Are you getting this down? It’s good! We should make a play out of it!”

Brooke was getting it down, and by November 2011, she thought it might be a play. She got in touch with a Pittsburgh theater director, Tracy Brigden, and gave some background: In addition to being a poet, Nelson had studied clowning. She was a Christian Scientist and wrote the “Looking Homeward” column in the Christian Science Monitor for 10 years. She had three children—Derek Nelson ’80, Todd Nelson and Brooke.

And she really did have four noses—prosthetic ones, a result of cancer that had spread across her face. By the time she moved in with Brooke and Rains, Nelson was sleeping only in 45-minute stretches and needed around-the-clock care.

Brigden was putting together a June 2012 festival of new plays. She wanted to add Brooke to the schedule. “Mom died Jan. 31,” Brooke says, “and I got to work. I had this deadline, June 1, for this thing I had not even conceived.”

In writing the songs and script, Brooke drew from her daily routine with Nelson. Each morning by 9, she’d go to her mother’s apartment. “Her nose might or might not be on. She’d be working on her poems, going through the L.L. Bean catalog. We’d read psalms or the Christian Science lesson. We’d sing hymns, listen to Andrea Bocelli, Plácido Domingo, The Sound of Music.”

Nelson’s favorite movie was The Red Shoes. “She’d say, ‘Have you seen The Red Shoes?’ and they’d watch the same 20 minutes of it four times in a day. “She’d hold court,” Brooke says. “She loved to joke with you about your nose. She’d say, ‘I’m a very important poet, but you have a wonderful nose. Is that your nose? You know, I can take mine off.” One morning Brooke came down to find her mother, sans nose, wearing sunglasses and singing, “Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen.”

When she couldn’t find the right word, Nelson would crack jokes and make puns. Other times, she’d sing the Cream of Wheat jingle. “We were lucky,” Brooke says, “that with Mom, her core essence surfaced, which was a loving, generous, childlike-in-the-best-way persona.”

Much of “Mom’s Daily Theater” made it into the play. On stage at The Duke, Brooke spoke of coming to see her mother at breakfast:

“She had her nose tied upside down to the bridge of her glasses through its nostrils. She had already tried scotch tape and glue stick. She asked me, perfectly innocently, if it was acceptable. I told her it was very clever indeed and I thought it would pass muster. ‘Who’s Muster?’ she said. ‘We don’t know anybody named Muster—Gotcha!’ Mom’s noses are brilliant maxillofacial works of art. My mother was also a piece of work. I loved her so much, but I never knew how much, until now.”

From that monologue, Brooke moved into song:

Are you getting this down? These dark and crazy scenes

Are you getting this down? The laughter in between

’Cause everything I wanted eluded me each time

The only thing I ever knew was mine,

The only thing I ever knew was mine,

Was your love. Your love.

More than 15 million Americans provided 17.7 billion hours of unpaid care to friends or relatives with dementia last year, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. Nearly 60 percent of dementia caregivers rated their emotional stress as “high” or “very high”; more than one-third experienced symptoms of depression.

As Brooke learned, this is in part because dementia caregivers never know what to expect. “She would change,” Brooke says of her mother, “and there would be another new normal that I would have to figure out: This is a whole new Mom this week. This is angry Mom. This is cuckoo Mom who can’t remember how to put on her nose. You have to let go of your conception of the person.” Brooke spent much of each day problem-solving: Was Nelson in pain? Was she hungry? What would make her happy: Singing? Reading the Bible? Watching The Red Shoes?

While writing the play, Brooke would spend all day in the music room near her bedroom, where she’d read pieces of script into her Photo Booth video app, watch her delivery and rewrite from there. Sometimes, Rains would come in at 10 p.m. to remind her to eat dinner.

The first public reading was at Brigden’s Momentum Festival of New Plays. “I’ve never been more frightened in my life,” Brooke says. “But if I’m not scared, why bother? I mean, I was terrified taking care of my mother.”

The response from the Pittsburgh audience was exactly as she’d hoped: “that they would take away the love story at the root of it all.” Earlier, in December 2012, “we got this idea to do a fan funding campaign” for a companion CD. The campaign raised nearly 300 percent of its goal; it paid for the record and more workshops.

The Warner Theatre in Torrington, Conn., asked to do the world premiere. Sara Hannafin, then director of development at the theater, explains: “A good friend casually mentioned to me that Jonatha Brooke had written a play. I knew her work as a singer. I knew how talented she was.” Hannafin saw a chance to raise money for the theater and to bring in a new audience. She went to Brooke’s website, found contact information and sent an email.

Before long, Hannafin found herself watching the performance in Brooke’s living room.

The Warner show took place in June 2013. “We sold it out,” Brooke says. “We had one day to go in, figure out how to light it, what it would look like, sound check, and then we did it the next day. And we did it again at the Philly Fringe Fest in September.” Again, the show sold out.

“I would do it again in a heartbeat,” says Hannafin of hosting the premiere. “I’ll never forget it. The show is literally for everyone. It gives you this intimate portrayal of caring for a loved one. I don’t think there was a dry eye in the house.”

Brooke and Rains started quietly raising more money to bring the show off-Broadway. “And we just went for it,” Brooke says. The show ran for 10 weeks at The Duke. Night after night, sniffles from the audience intensified her performance, and no song elicited more tears than “Time,” which is about being unprepared for her mother’s death:

I’m not ready any more

I thought I was, but there’s the door

I’m not ready like before

So give me just a little more time.

Please don’t come today

Tomorrow’s not good either

’Cause I know, it’ll mean forever.

“Time” is “devastating and gorgeous,” raved the New York Times. The show was a critics’ pick in the Times and Time Out New York. Characterizing 4 Noses as “unavoidably sad, yet poignantly funny,” the Times praised Brooke for “the artistic demands she makes on herself here as a writer, musician and actor.” Brooke “gives voice” to heartache, wrote Entertainment Weekly, “without ever veering into mawkishness” in narrative and song: “The Amherst grad punctuates her story with the kind of amusing, acute details that marked her earliest lyrics.”

Of the critical response, Brooke says, “we had no idea what to expect. You sort of think, Are they just being nice to me because I’m 50? Are they throwing me a bone?” Her friends dismissed the idea: “The New York Times,” they told her, “does not throw anyone a bone.”

After each show, it would be “a cry fest” in the lobby, Brooke says, with audience members sharing their own stories of caring for parents, siblings or spouses. On the show’s website—fournoses.org—she invited fans to post personal stories, poems and photos.

One man wrote of caring for his father: “What happens when the child becomes the parent? Fear happens, and sadness, and guilt, and confusion, and about a thousand other things. … I am so grateful to have discovered My Mother Has 4 Noses. It is a show that reflects the highs and the lows of one of the most difficult parts of my life.”

“I started saying goodbye to my mother sometime in 2003,” wrote one woman. “She and I have parted ways a thousand times since. … I only know that she is a new stranger every time we meet again, as much to herself as to me.”

Many posts address Brooke directly. “Jonatha,” wrote one husband, “your songs from My Mother have touched my heart, and sometimes torn it apart. My wife is disabled from orthopedic issues, and suffers from bi-polar disorder. … Your songs convey the same feelings of love and loss, and the sometimes overwhelming burdens that wash over me. I see myself in these songs, I see my wife, and I see the struggles (and successes) that we experience every day.”

The first song Brooke ever wrote was at Amherst, in Professor David Reck’s introductory music composition course, which she took sophomore year. The first assignment was to choose an e.e. cummings poem and set it to music. “It was like being hit by lightning,” Brooke says.

She chose “love is more thicker than forget,” and the resulting song is on two of her records, Grace in Gravity and Live in New York.

She and Kimball (her partner in The Story) approached Reck with the idea for a Special Topics course in which they’d create a concert of original songs. “He gave us full course credit to write and then perform the songs,“ Brooke says. “I think we got an A.”

Thirty years later, her mother’s own poetry appears in 4 Noses. The song “Scars,” for example, takes its chorus from a Darren Stone Nelson poem, “Words About Writing,” which instructs a younger writer, “Start again, more than you ever dreamed you could.” Brooke sings:

So you start again, more than you ever dreamed you could

Start again, again, again

Start again, when no one thought you would.

Brooke once found a scrap of paper in her mother’s trash. It was another of Nelson’s poems, “Song.” Her mother had scribbled in the margin, “probably written around 1950—should we sell it to Hallmark Cards?” Brooke decided to finish the poem. The result is “Mom’s Song,” which she sings near the end of the show:

And now I know a lot about a little bit of you

The innocence and the ignorance and the love that got us through.

’Cause you’re the one I want to learn by heart before I die

It’s still your eyes that make me smile, and it’s still your eyes that make me cry.

Your eyes, so blue

My love, it’s true

Your eyes, my tears

You know the only place I feel at home

Is here alone with you, my dear, it’s true.

In lyrics such as these, and in the music, and in the stories that Brooke spent two years getting down, the tragedy is impossible to ignore, but so is the love story.

Katy Perry and Quadroon

Brooke hopes to bring My Mother Has 4 Noses to other cities. She’s been busy with other projects, too. She co-wrote two songs with Katy Perry. One of them, “Choose Your Battles,” is on Perry’s new pop album, Prism, and features Brooke on kalimba—a thumb piano.

Brooke is also at work on three new musicals, including one with pianist, keyboardist and composer Joe Sample. She is writing songs for his play Quadroon, which is based on the true story of Henriette DeLille, a free woman of color in 19th-century New Orleans.

DeLille’s mother, a free Creole woman, had a marriage-like “alliance” with an already-married white man. This system, similar to common-law marriage, was called “plaçage,” and DeLille was expected to enter into it as well, but she instead wanted to be a nun. In 1842 she founded the Sisters of the Holy Family, the first order of African-American nuns. “The musical is an embellished version of her story,” Brooke says.

Emily Gold Boutilier is the editor of Amherst magazine. Photos by Adam Krause