He became one of the greatest poets of his generation, but first he was a member of the class of ’47 at Amherst, where he developed an obsession with memory and a transformative interest in Proust.

IN SPRING 1944, Jimmy Merrill enrolled in English 1. The course was the creation of Theodore Baird, who, breaking with standard procedures for teaching grammar and argument, treated writing as a tool for intellectual exploration and experiment: the aim was to find out what and how one thinks by writing. But before students could use composition for self-knowledge, they needed to be shown how conventional were their notions of the world and how little they really knew about it.

Baird might enter the classroom by climbing through a window and ask his students whether it should not be called a door. Such theatrics were distantly indebted to the philosophy of William James. But the course communicated its guiding ideas only indirectly through passages from modern autobiographers such as Henry Adams. Writing prompts were meant to puzzle students and force them to use self-reflection to find a way out of their bafflement.

Baird might enter the classroom by climbing through a window and ask his students whether it should not be called a door. Such theatrics were distantly indebted to the philosophy of William James. But the course communicated its guiding ideas only indirectly through passages from modern autobiographers such as Henry Adams. Writing prompts were meant to puzzle students and force them to use self-reflection to find a way out of their bafflement.

The two-term course was required of every student. In 1944 it was team-taught by Baird, Reuben Brower and G. Armour Craig ’37. Craig was in charge of Jimmy’s section. Craig went on to teach at Amherst for 45 years and serve briefly as college president. But in 1944, he was new on the job, and the 18-year-old Merrill (above) liked to lean back in his chair and test his teacher with questions about fashionable contemporaries like Jean-Paul Sartre or Albert Camus. Students would laugh about Jimmy’s impudence and imitate his drawling questions after class.

Jimmy was already resistant to Meaning with a capital M. This stance would develop into the militantly casual diffidence about ideas that can make Merrill seem anti-intellectual in his mature approach to poetry. But he had an intellectual, in fact an academic, justification for his attitude in his education at Amherst. The dandified French aesthete he was growing into was being influenced by American pragmatism as embodied in Amherst English and its composition program in particular. Merrill liked to say that he wrote in order to find out what he thought, and he never knew what he wanted to say in a poem until he finished it. Baird would have approved.

Merrill took two classes with Baird, but the teacher who affected him most deeply was Reuben Brower. Brower was a learned, genial, quietly charismatic professor of Greek and English—an unusual double appointment. His training in philology and New Critical close reading combined with a stress on the sound of literature that was particular to Amherst. Brower, like Baird, had encountered Robert Frost at Amherst, and he assimilated Frost’s insistence on the dramatic nature of poetic language and the role of voice in creating meaning. It was a piece of local lore at Amherst that the young Ben Brower had volunteered in Frost’s class to read aloud an obscure Elizabethan poem, after which the white-haired poet declared before the class, “I give you an A for life.”

The story captures the approach to literature that Brower developed out of Frost’s poetics. “Literature of the first order,” he said of his method as a teacher, “calls for lively reading: we must almost act it out as if we were taking parts in a play.” Oral performance of a text, a nuanced reading that entered into and communicated the tone of a poem, voicing meaning rather than decoding it, was itself an act of interpretation; and poetry was the quintessential literary form because of its verbal density and reliance on voice. But Brower brought the same focus on “the sound of sense” (Frost’s phrase) to the novel, and he helped to develop Merrill’s appreciation of fiction too. Jimmy read Jane Austen in tutorial with him, and Proust would be the subject of his senior essay under Brower’s supervision.

Above: Between a god and a poet:

As a 19-year-old at Amherst in 1945, Merrill posed with a head of Hermes and a life mask of Keats.

Merrill had first encountered Proust in freshman composition, where he was one of the autobiographers Baird featured in that course (indeed Proust was the source of more examples than any other author assigned). He at once became a transformative passion for Merrill, sweeping away Baudelaire, Wilde and Elinor Wylie like schoolboy crushes. Asked by an interviewer years later why Proust meant so much to him, Merrill pointed first to the scale of Proust’s seven-volume novel, its “wonderful size.” But À la recherche du temps perdu was not War and Peace or Bleak House (big books Merrill came to love later): Its setting was Belle Époque French society as seen through the prism of Proust’s life; its monumentality contrasted with the subjective focus epitomized in the stand-alone, quasi-lyric passages picked out by Baird (such as the pages about the madeleine, the steeple of Sainte-Hilaire and Marcel’s obsession with actress Berma). The novel’s material was the life of a writer rather like Jimmy, an exquisitely self-conscious young man at ease in wealthy society, preoccupied with music, art, drama and books, whose tale begins with a boy alone in his room, desperate for his mother’s good-night kiss.

MERRILL’S OBSESSION with memory dates from his time at Amherst. With Proust as tutor, he began to remember “so much of my own life”—he was just 18 when he wrote this—“that said life is beginning to appear immensely richer than it really was or perhaps it really was + I never knew it.” The Southampton home of his childhood figured largely in his “disjointed memories,” he told his friend Frederick Buechner, including the wallpaper pattern in his bedroom, his father’s Irish setters and the jigsaw puzzles he pored over “until Mamma became convinced I was going blind doing them. All of these [memories] make up a puzzle so much greater + more blinding.” These are the metaphors he would explore in “Lost in Translation,” his Proustian memory poem written 30 years later. “Everything will remind me of something now,” he concluded, as you might speak of an affliction or gift.

Proust’s homosexuality and the homosexual themes of the novel were a crucial part of Jimmy’s identification with him. About the direction of his own desires, Jimmy was entirely clear. Back in 1942, he’d written a letter to his mother justifying his refusal to attend society dances in New York. “You have to understand this: it is more than just disliking dances.” He simply could not bring himself to act like “one of the fellows.” “I have accepted this feeling,” he said, “and I believe there is nothing you or I can do.” The pressure that mother and son both felt about this issue expresses a mutual awareness that much more was at stake than whether he would show up to a Junior League ball.

Jim, as his Amherst teachers and classmates called him, was known to everyone as Charles Merrill’s son. Merrill Lynch, in the midst of major reorganization and a national marketing campaign, was a prominent national brand, and the co-founder of the firm arrived at his alma mater (he was a member of the class of 1908) like a potentate, chauffeur-driven onto the gridiron to cheer the purple-clad Amherst football team. Even if he refused to join his father’s fraternity, Chi Psi, Jim did not shrink from association with him, and the fact of his own wealth. “He was smarter, richer and maybe better than the rest of us, and we wanted to get as much of him as we could,” remembered Bob Wilson ’47.

“Everything will remind me of something now,” Merrill (third from right, in Crete) once wrote, as you might speak of an affliction or gift.

Jim had the good fortune to draw as his freshman roommate Horton Grant, a bespectacled, sweet-natured boy from Los Angeles. The two were active in Amherst’s theater scene, which included a role for Jimmy as the butler in P.G. Wodehouse’s The Play’s The Thing in fall 1943. Jimmy joined the Masquers, which grew into the Kirby Theater Guild. The group made a respectable alternative to weekend excitement at the football field.

Hanging over Merrill’s first three terms at Amherst was the knowledge that he would be called by the Army after his 18th birthday. His father urged him to prepare by getting himself in top shape, but all he managed were a few wistful walks in the hills. In May, interrupting his studies in the middle of his sophomore year, he entered the Army Enlisted Reserve. Reporting for duty on June 14, 1944, at Fort Dix, N.J., he buttoned up a private’s uniform. A month later he was sent to Camp Croft in South Carolina, where he learned to march, clean a gun, dig a foxhole, wear a gas mask and crawl under barbed wire while explosions roared overhead. Somehow he had time to read a lot: this “Marcelomaniac” was consuming quantities of Proust; poetry by Rilke, Yeats and Valéry; and novels by Stendhal and Henry James. His mind drifted to Isabel Archer and the “Archaic Torso of Apollo” while he was making notes about the range and caliber of ordnance.

“I am in this dreadful affair,” he wrote about the war to Coley Newman ’45. “I have a very good chance of being killed or emotionally sterilized.” He was afraid of “losing time” “cleaning the latrines,” not to mention the prospect of dying on the battlefield. “I have such a huge desire to live […]. I want to write so much and so well[.]” That letter was written shortly before he learned that David Mixsell, his prep-school nemesis, had died from combat wounds in France. It was hard for Jimmy to know what to feel. “Elegy for an Enemy,” a poem he wrote in response to the news, begins,

Death was by far too good for him, we said.

The small, pale eyes, the soul of blunted lead.

The snake-swift smile tracing the shape of dread.

Can he be dead?

Not long after that came a shocking report from Amherst: Horton Grant had died in a car crash one Saturday night, along with a buddy and their two dates. It wasn’t necessary for a young man to go to war to die an arbitrary, violent death.

Jimmy also had his father’s health to think about. Decades of hard living and the strain of his recent work for Merrill Lynch had left Charlie’s arteries blocked and his heart vulnerable. In April 1944, he suffered a major heart attack, followed by another in July. With his father’s life threatened, and his memory stimulated by Proust, the 18-year-old soldier longed to return to childhood. A letter from his nephew Merrill Magowan released a flood of feeling in him. The little boy described being left alone in a rowboat and drifting “all the way over to the swans” before he was rescued.

“That phrase,” Jimmy wrote to his mother from Camp Croft, “somehow makes me so homesick for not Southampton but for being a child again, being in a position to experience the fear and magical delight of the little boy caught among the big white, beautifully evil birds, to utter the squeaks and gasps he must have uttered. I envy him more than I can say for that.” Barely having come of age himself, Jimmy looked into his past and found a character who would soon appear in his poetry: a child magnetically drawn to the “beautifully evil” swans.

In late 1944, he took an Army physical exam, for which he prepared by popping Benzedrine, hoping to push his heart rate up to an alarming level. But that was unnecessary: his eyesight was found to be poor, and he was designated for “limited service” only, which meant that he wouldn’t be sent overseas; he was assigned to the typing pool. Then, in January 1945, with Allied troops advancing on the Rhine, he was abruptly discharged.

Back at Amherst, he was summoned to an audience with a distinguished campus visitor: Robert Frost. The poet was 70. He wore old-style black shoes laced to the ankles. Rheumy and tired, yet “with brilliant blue eyes and an enchanting smile,” Frost read and reacted to Merrill’s poems. He warned the young man away from “vague words,” while praising him for phrases that forced readers to “say things in a new way.”

MERRILL’S SENIOR ESSAY on Proust, “À la recherche du temps perdu: Impressionism in Literature,” begins by discussing French Impressionist painting, but his real subject is Proust’s complex use of metaphor. The power of metaphor, he explains, is that “it permits discovery. What is unknown may be known through analogy, as Einstein is said to have taught a blind man what ‘white’ is by letting him feel the neck of a swan.” The essay is, throughout, a controlled academic performance. Yet there are glimmers of the personal where more is at stake.

While discussing the opening of Sodome et Gomorrhe, where Baron de Charlus and the tailor Jupien meet and then disappear to make love, Merrill has this to say: “The homosexual, [Proust] tells us, is […] a member of a race that must live by falsehood and perjury, obliged like a Christian on the day of judgment to renounce his strongest desires.” But there is nothing so eccentric, Merrill insists, about the homosexual: “Such a man is shunned not so much for his difference from other men, but because these others recognize in him certain fleeting aspects of their own natures.” A few pages further, describing the “protecting surface of metaphor” in Proust, Merrill perhaps describes some of his own motives for writing: “It is as though we were skating upon a sheet of ice that had formed above a black torrent: we may skate with an assurance of safety, but the ice does not make the water beneath us less terrible.”

The essay was a smashing success with the English department. Richard Silva ’49 remembers Brower walking into class and announcing, “in the most reverent, even awestruck manner that Merrill had turned in his senior thesis on Proust, that it was brilliant, and that we were all privileged to be students at the same time and in the same place as Jim Merrill, who was destined for some sort of greatness.”

Having finished his senior-year classes and submitted his thesis in February, Jimmy had time on his hands before commencement. He spent inordinate time on plans for a spring costume party. Merrill inherited his love of parties from his parents. But he was also influenced by the soirees that punctuate Proust’s novel, and parties show up at important points in his own writing. Parties satisfied his faith in frivolity as a balm and his pleasure in drama and ritual, costumes and masks.

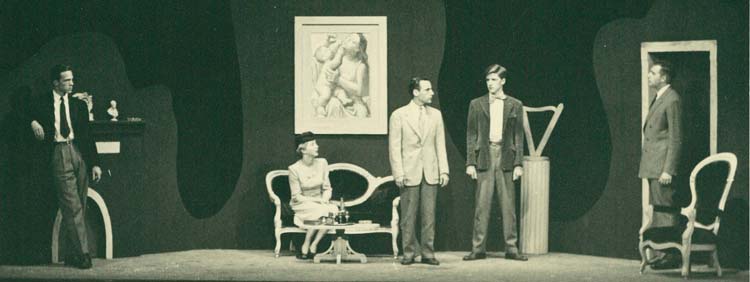

Amherst produced Merrill’s play The Birthday in 1947. It has qualities of comedy but also veers toward the mystical.

These elements were combined in his one-act play The Birthday. Written during summer 1946, it was produced by the dramatic arts class at Amherst in May 1947. The play concerns a birthday party for an ordinary young man named Raymond. The sly, distinguished host is Charles. The guests are Max, a painter; the society matron Mrs. Crane; and Mr. Knight, “a wizard.” The name “Charles” came from Merrill’s father and brother—he would use it several more times in his work to create a comic alter ego.

The play has the setting and clever dialogue of drawing-room comedy, but it veers at once toward the mystical, since it isn’t in fact Raymond’s birthday: the occasion being celebrated is purely symbolic. Raymond thinks he knows none of the others, and yet each of them represents some aspect of the person he will become or a dimension of himself he has yet to learn about.

Merrill was ready to see his life as an adventure, as Raymond is encouraged to; and at 21 he hoped the adventure was beginning. When the question of what he would do after college came up at commencement, he replied mildly, “Oh, nothing,” smiling to himself about how much he intended to accomplish (in life, in art) without going to work like other graduates, while aware of how much work that might turn out to be. Raymond runs away from his birthday party. He fails to grasp the sort of drama he’s been thrust into; or maybe he understands perfectly well, and shies away from the task of self-creation before him, unsure how to begin.

Langdon Hammer is the author of James Merrill: Life and Art (2015, Knopf), from which this article is adapted. He is a professor of English and American studies and chair of the English department at Yale.

Photos: Amherst College Archives. Kimon Friar/Courtesy American College of Greece, Attica Tradition Educational Foundation. Courtesy George Lazaretos.