Photographs and Text by Mary Beth Meehan ’89

In photographing strangers, one alumna tries to understand something of the people who live in her city.

Last year I began walking around Providence, where I live, and photographing strangers. In my career as a photographer I have worked mostly candidly, responding to an action as it unfolds. With this project I wanted to explore portraiture: someone agrees to be photographed by me, but then what do I do?

I published the images online, writing about the people I was meeting as well as my process. I wanted to examine how the pictures happen, as well as the ethics of trying to represent another human being. This June eight of the portraits were reproduced as banners up to 40 feet high and installed on buildings in the city. The result has startled me. The mother of Darnell, the boy with his hands in prayer, says she drives by the portrait every day. She tearfully thanked me for having shown her son’s tender side. A man who works in the building where Darnell’s portrait hangs, an arts center, says the energy inside it has changed completely: young people of color seem to have taken more ownership of the place. Fernando, from Guatemala, pictured outside his auto shop, says many immigrants are now asking his advice on how to succeed in this country.

Gazing into strangers’ eyes and asking them to reveal themselves turns out to be a radical act. Normally, we travel our well-worn routes and aren’t quite interested. This project has led me to question how we see one another: What do we think we see? How much do we miss? What remains unseen?

DARNELL

Darnell’s mother thinks he looks high in this picture: glossy-eyed, thin, struggling with life. She says it shows the pain he was in when I met him.

I first met Darnell over the summer, at the Community Boating Center, where he was working. He was open, laughing, horsing around with his friends. Everyone calls him Bookie (pronounced Boo-kie). One of his legs was encased in a cast from thigh to ankle. I asked him what had happened. “I got shot,” he said.

I was surprised, curious about this boy. I asked if I could make his portrait. Bookie, who is now age 17, agreed. He took a couple of days to get his hair cut and ask his mom’s permission, and then we met, outside his family’s apartment, in South Providence. We made some photographs in the courtyard behind the building, but he was jumpy, nervous, looking up every time a car went by. I tried to get him to talk about the shooting, but he was reluctant. He said he didn’t know who did it, didn’t know why it had happened. He asked if we could finish up quickly. Near the end of the session, he asked if I would make a few pictures with his hands held in prayer.

When I finally reached Bookie, by phone, weeks later, he told me he had moved—to North Carolina. “I was getting in too much trouble in Providence,” he said. He told me I could take the finished print to his mother, and he gave me her phone number.

His mother’s name is Erica; we met at the entrance to her building on a Saturday afternoon. She led me upstairs, past dozens of framed photographs: of her four children on the football field, at the prom, in colorful caps and gowns. Inside the family’s apartment, every shelf was crammed with trophies: football, basketball, cheerleading. There were more photographs, from family vacations, plus inspirational sayings about motherhood, laughter, faith.

While Bookie’s father watched basketball on TV, I showed Erica the portrait I’d made, and she said she loved it. She then called him, and he appeared on the cell phone’s small screen. She held up the photo to show him; he said he liked it. Then she asked his permission to tell me what had happened to him. He agreed, and they hung up.

“I was getting in too much trouble in Providence.”

Bookie had been at Bishop Hendricken High School, playing sports, doing well, following in his older brother’s footsteps. But once that brother had left for college, Bookie kind of went off the rails. At around age 15 he started getting high and drinking; then he got kicked out of school. With some neighborhood kids he’d known since they were little, he joined a gang. Erica said he turned dark, sullen, and they began arguing. She grew anxious and depressed, stopped sleeping, didn’t recognize this child who had been so happy till then. She said that when her phone rang once at 2 in the morning, she knew he was in trouble. Bookie had been shot. Two bullets had entered his left leg, shattering the tibia; another one had grazed his back. She said that when he got home from the hospital he was terrified, and the boys in the gang started coming around again.

Erica wasn’t sure how to help her son, and then it came to her: she had to get him out of Providence. She called her sister in North Carolina and made arrangements for Bookie to go to her. She told him the plan and bought him a plane ticket; he didn’t put up a fight. Since then, she said, he’d gotten clean, put on some weight, enrolled in an online course for his high-school diploma. He’d even gotten a job, standing outside a tax preparer’s office, wearing a Statue of Liberty costume to attract customers. “He would never have done that here,” his mother said, laughing.

Looking again at my portrait, Erica pointed to Bookie’s prayerful hands. She said he’d since gotten a tattoo on his shoulder of that image, but she wasn’t sure why. I said: could we call him back and ask him?

Bookie laughed when he appeared again on Erica’s screen. “Bookie,” she said, “in that picture, why’d you do the prayer sign?” “Because I pray every day,” he said. “And because I’m blessed. God was by my side the day of the shooting.… It’s a blessing from God for making me able to speak to you guys right now.”

Erica said she’d call him back later, and Bookie said that he loved her. She hung up and turned to me: “He had gotten out of saying ‘I love you,’ and all that stuff.”

MARINA

On the East Side, clustered around the Providence Hebrew Day School, on Elmgrove Avenue, is an enclave of Orthodox Jews. I live near there, and when I walk to the store or take my children to the playground, I often see the members of this community, the men wearing stiff black hats, the women with their hair covered and long skirts concealing their legs. When I pass them on foot, I say, “Hello,” but often they don’t meet my eye. Sometimes I put an extra effort into greeting them, to see if they’ll respond to me. Over time I began to notice something that I didn’t like: when they didn’t engage with me I would get angry. And when I saw the women, with their bodies encased in clothing and their many children trailing them, I would think how oppressed they must be. I’d get angry about that, too.

When I began making portraits of Providence people, I decided to try to include someone from this community. I contacted the Hebrew school’s rabbi, and, after a series of phone calls, emails, meetings—and even a letter of reference—he asked me to write a short description of my work, which he said he would distribute within the community. Slowly, there followed a wave of openings; I, with my camera, began to be invited in.

I was invited to a morning prayer service, to a winter Purim parade, to a communitywide fundraiser. At one banquet a young woman approached me and said, “You must be the person who wants to meet us.” We chatted, and I asked if I could speak with her again, at her home. When I later got to her house, as arranged, she told me that she’d called the rabbi—twice—to make sure it was okay to let me in. Thinking of the women who didn’t say “Hello” to me on the playground, I asked her why she’d been so wary. She said that all four of her grandparents had been in the Holocaust, and that that colored the way one looked out on the world. This stopped me cold.

During the weeks that followed, I photographed many people in the Orthodox community, including students at the Hebrew school and an elderly rabbi who had taken in two non-Jewish homeless men, saying, “The Talmud doesn’t talk about love for fellow Jew; it talks about love for all God’s children.” But I remained most interested in the women.

“True beauty must stem from one’s deeds, speech and thought, and it radiates from the inside out.”

For many of the women, the idea of being photographed conflicts with the law of modesty. This topic launched numerous conversations, in kitchens and on front steps, as the women explained to me that the law of modesty led to a kind of freedom: from the world of appearances, from the outside culture’s obsession with women’s bodies, from the gaze of men other than their husbands. Many refused to be photographed, especially if their names were to have been used and their pictures seen widely. But then I met Marina.

Marina was born in Russia and raised as a non-Orthodox Jew, but as an adult she had converted to Orthodoxy. She is now a professional in the financial sector, in Providence. She acknowledged that the law of modesty is complicated, and that in some Orthodox communities it is indeed used to subjugate women. But as someone who has chosen this spiritual path—and written two books on it—she has come to revel in the liberation that the law enables.

“True beauty must stem from one’s deeds, speech and thought, and it radiates from the inside out,” she has written. She described a culture that I know well: one that worships youth and beauty, in which adolescent girls, consumed with anxiety about their looks, often fall prey to eating disorders. Marina said that within the bounds of modesty there is room to concentrate on one’s inner virtues, to see oneself as completely human, regardless of how one’s body, social standing or material wealth conforms to society’s standards. And she referred to the Orthodox community as a source of support, within which the outside culture’s superficial rules are irrelevant.

When I first met Marina she’d been wearing a snood—a crocheted covering of her head. When I returned to make her portrait, she was wearing a wig. It brushed her shoulders and framed her face in thick bangs. When we stepped outside to make the picture, the late-evening sunlight glinted off the auburn strands.

Back in the house, since we were just two women alone, I asked Marina if she would show me her hair. She said, “No.” She asked if I would get naked in front of a stranger, even if that stranger was another woman. I said, “Probably not.” She said that it was the same thing; my modesty was akin to hers. “It’s private,” she said.

Not long after, I saw a group of Orthodox women and children at the neighborhood playground. I have a plot at the adjacent vegetable garden, and while I was working there my T-shirt and pants had gotten muddy. I spotted some of the women I recognized, and I was tempted to say “Hello” to them. But I was self-conscious about my appearance, and didn’t want to intrude. I noticed, though, that nowadays I feel differently about them.

OMOWUNMI

She told me all this inside the sweet yellow bungalow she shares with her husband, off Mount Pleasant Avenue. She’d invited me there to tell me her story. When I first arrived, we stood in the entryway talking. “Where are my manners?” she suddenly said, and took me into her living room. While we talked she served fried fish and fruit, and cold drinks.

I had first met Omowunmi at the Chapel of Peace, a small church on Potters Avenue; I’d been attracted to it by the name. Her husband, whom she had met and married in their native Nigeria, is the chapel’s pastor. She had wanted to marry a man of God, and had dreamt of him almost 10 years before she met him. There were others who wanted to marry her, but she knew that he was the one.

Before coming to the United States, Omowunmi was trying to make a living in her country, selling bottled soda and bread on the roadside, when her uncle told her she’d won “the lottery.” He was in Providence, and had entered her name for a green card. She was selected.

When her car turned out to be a lemon, she learned to be a mechanic.

Soon after she arrived here, almost 20 years ago, she bought a used car, for $800. It turned out to be a lemon and cost more than that to be fixed. So that this would never happen again, she decided to learn to be a mechanic.

Omowunmi’s father was a Nigerian soldier in World War II, and she adored him. He died when she was 8. From then on she’s wanted to honor him, by living a life of discipline and service—first as a soldier, now as a wife and a teacher of Sunday school, and then in whatever callings might follow.

Last year Omowunmi got her bachelor’s degree at the University of Rhode Island in healthcare services, and she now works at a veterans’ hospital. Her nickname is Peace. She’s thinking about changing her name permanently. It’s easier for Americans to pronounce, but, more important, she loves the word. “I love the meaning of that name.”

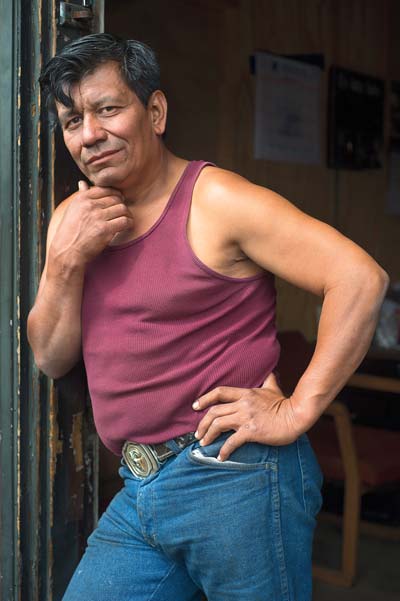

FERNANDO

Sometimes I see a perfect picture in front of me: the light, the color, the mood, the gesture. The person. In my mind is the criticism that we photographers objectify people, that we commit “the violence of the aesthetic.” But at this moment, I am only thrilled by what I see.

A man is leaning against the doorway to a mechanic’s shop, in Olneyville; his hand is resting under his chin. I’m afraid this will change, so I walk quickly toward him. I hear men all around me speaking Spanish, so I hold out my hand and say, in Spanish, “Please don’t move. Would it be okay if I take your picture and explain later?” He says, “Sí.”

His name is Fernando. I ask where he is from and he says Guatemala, but he doesn’t have time to talk. I go back on another day to give him a print, and to find out more about him.

We walk through the garage and he offers me a seat in his tiny office. I ask him about Guatemala. He tells me about a difficult passage through Mexico, and crossing the Rio Grande on foot on his way to this country. That was 16 years ago. For seven years he has owned this shop. I tell him I want to write something about his life, and he explains that writing is something that he loves to do. When he’s gotten home from work, after he’s had a shower and begun to relax, words come to him: about a woman he loves and is trying to win back, about his gratitude for a healthy son, and his resolve to keep working so the boy can stay in private school, in East Providence. He records them in the “notes” section of his phone, which he pulls out and shows me. He plays me a video of himself, singing a love song he’s written. His voice rings out, full of longing.

He sings a love song. His voice is full of longing.

When I began this project, I wrote about Providence as a pie chart of percentages, of immigrants coming from Central and South America, the Caribbean, Southeast Asia, West Africa. But as I sit in this man’s company, I realize how reductive that is, how those ideas just eclipse the fullness of a person.

ANNYE

I’m sitting in my car in Washington Park, in front of a big white house with red trim, and I can’t believe what I see: Annye is walking onto the porch and down the steps, decked out in a sun-yellow suit and plum-colored hat. After weeks of introductions and phone calls and being cajoled, she has finally submitted to my making her portrait. I’m excited but also a little worried that I won’t do her justice.

She didn’t want to be singled out, didn’t want any “glory.”

When Annye and I were introduced she was polite, but when she heard about my wanting to make photographs she said, “No, no, no!” She didn’t want to be singled out, didn’t want any “glory”; but she did give me her phone number, saying that I could call her. Nighttime was best, she said. During the day she was “always running,” doing errands for the elderly, visiting the sick. But at night she stayed home reading—the Bible and African-American history. Sometimes, she said, she’d get so engrossed in her reading that the sun would come up before she turned out her light.

Many weeks and many conversations followed. I learned that in 1959 Annye had come to Providence from Montgomery, Ala. She’d answered an advertisement in the newspaper, placed by an East Side widower who was looking for a live-in caretaker for his three children. She met other domestic workers in Rhode Island, many of them also Southern black women—some of whom had college degrees but found that they could make more money here, taking care of white people’s children, than they could in their professions in the South.

I learned that Annye had had eight children, that all had been well educated—“Thanks be to God”—and that one had even had an audience with the pope. But there were many questions Annye refused to answer. She wouldn’t tell me her age, and was stony silent when I asked about the father of her children. “No, no, no,” she said. “That’s a sore subject.” But she finally agreed to a photograph.

So on this spring evening she gets into my car and I suggest that we go to Roger Williams Park. She agrees, saying she remembers many evenings there, with her children in pajamas, enjoying a dinner under the trees, on a broad blanket spread with chicken, potato salad, chocolate cake and punch.

We get out in front of a beautiful old tree—“This tree is older than the both of us”—and as I work Annye is patient with me in ways I’m grateful for.

When we are finished and back in the car, she hands me something that she says she’s written and would like me to quote. Here’s an excerpt:

Annye R. P.

Community Missionary

Is a fanatic when it comes to Serving God, about Obtaining a Religious Education, Scholastic Education, Black History Education … Service to your Fellow Man, Especially the Elderly, and Teaching and Training our young people to Utilize their God-Given Gifts and Talents.

Not to Expect Anything In Return but God’s Grace, Mercy, and Blessings.

When it’s all over remember whatever you have done for the last one you have also done it unto God.

May the Work I have done speak for me.

Photographs and text © Mary Beth Meehan, 2015. To see more from this ongoing project, go to marybethmeehan.tumblr.com.