By Emily Gold Boutilier

How long do your eyes linger on an object in an art museum? Thirty seconds? Two minutes? Ten minutes? Imagine studying a single painting for an entire semester. It’s not a luxury; it’s an Amherst course.

In Professor Joel Upton’s seminar “The Art of Beholding,” each student picks one painting to focus on for four months.

Through a series of steps and presentations, the 10 students in the class move ever closer to what Upton calls “the threshold of beholding,” when “the art of the work of art” emerges before them.

“Beholding is not a synonym for observing or viewing,” Upton says. “It’s meant to introduce a radically different approach to works of art, and implicitly to our relations with human beings.”

In beholding art, he says, students’ “deepest sense of their own unique being gets revealed to them.”

To Will Kamin ’15, the class “makes a statement against today’s predominant culture of scurrying around museum galleries, from painting to famous painting, expecting some grand epiphany to present itself in each piece on the wall, but never taking the time to patiently, meaningfully engage with a work.”

Students come to see “their” painting “as an old friend,” says JinJin Xu ’17. They also learn to think in a new way. “Most courses teach reasoning, problem solving, pattern recognition and the incredibly important skill of making distinctions,” says Abe Kanter ’15. “Professor Upton teaches contradiction, dissolving distinctions and intimating reconciliations of infinite wholeness.”

As Marie Lambert ’15 identified contradictions in van Gogh’s Mountains at Saint-Rémy, she grew “aware of contradictions in my own life, contradictions between my duty to my family and my dreams, between what is practical and what I believe is right.”

The seminar “is the most important course I will take at Amherst,” says Xu. “Not only did I learn to look, listen and be with one painting, I also learned to be with my own solitude, and thus, respect and be with the solitude of another.”

This was life-changing. “My relationship with friends has slowly evolved from being a supplement for my own loneliness to a deeper understanding and respect for another individual,” Xu says, “and I feel that I am truly learning how to love for the first time.”

Madeline Ruoff contributed to this article. Illustration by Ellen Weinstein.

Upton’s Six Steps Toward the Threshold of Beholding

1Understand and acknowledge that to exist is to be separate and “to be separate is to long to be whole.” “Only in that contradictory tension,” the professor says, “can beholding occur.”

2Research the artist, origin, function and provenance of the painting.

3 Study the painting’s form.

4 Examine its iconography.

5Find pictorial contradictions in the painting with which their artist struggled. Some are metaphorical (time contradicting space, for example), while others are physical (brushstrokes contradicting the image as a whole).

6Now at the threshold of beholding, “intimations of reconciliation of contradiction” slowly emerge. By engaging with these “fleeting intimations,” students “meet the painter’s own beholding

face-to-face.”

See the Reading List and Seminar Checklist for “The Art of Beholding.”

What Does It Mean to Behold? Three students explain.

Abe Kanter ’15 on Giovanni Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert

I’m convinced that beholding is the highest form of art, that it is something we all need in order to survive and that it is something none of us do enough. You can never really know what an act of beholding is going to be like until you do it. In the case of the painting I chose, I ended up touched by the way Bellini painted a deeply religious and religiously important story as identical to what everyone sees every day. The light to which the saint submits in the painting is the sunrise.

Image from the Frick Collection

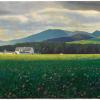

David Walchak ’15

on Rockwell Kent’s

Clover Fields

The beholding method builds to a very personal experience with a painting. It has to be different from the informational experience of reading a plaque about the work or hearing a curator discuss it. We researched our paintings throughout the semester, but we were discouraged from relying on that research to solely inform our presentations. It starts with the notion of not merely glancing at a painting. Professor Upton teaches us how to let the painting work on us a bit, how to give the painting time to do that. The class changed my experience of going to art museums.

Image from the Mead Art Museum

JinJin Xu ’17

on Ary Scheffer’s

Paolo and Francesca

I beheld for the first time at the very end of the semester. The contradictions within the painting had been laid out, and it pained me to see them all together, without seeing a way to reconcile them. As the contradictions overwhelmed me—the warmth of the background versus the coolness of the figures, the contradictory angles of their limbs, the paradox of a loveless contractual marriage versus the love found only outside of this contract, the judgment of Virgil versus the understanding of Dante, and their gaze on the lovers versus ours from outside of the painting— the distance between the embracing adulterous lovers grew until I realized the greatest contradiction: that they were inseparable in their embrace, yet separate for infinity. I saw my own solitude mirrored outside of the painting. I felt that I was rising up, in suspension with the lovers. I was brought to tears.

Image from Mead Art Museum