Last Man Standing

By George Bria ’38

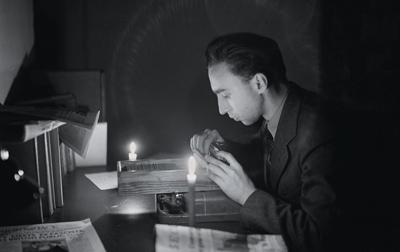

Introducing me at a journalism event in New York, the moderator asked, “How old are you now, George?” I said 96 (that was three years ago), and the auditorium burst into applause. It was the loudest cheer of the night, as I recall, and nothing had happened yet except the mention of my age.

What’s so special, anyway, about very old age except that only a tiny minority reaches it? The 2010 U.S. census counted 371,244 men and women ages 95 to 99, or just 0.1 percent of the population. And only 82,263 were men. Life expectancy, at last report, was 78.3 for men and 80.93 for women.

So cheers for us 99-ers. What’s our secret? Pure luck for me, I say. I never aimed for great age; it just came along. I did eat fish, grow my own veggies, play a lot of tennis. But so did people who died young, relatively. I’m just glad I seem to have most of my marbles, am free from severe pain, can walk (carefully) and, most of all, have a healthy 98-year-old wife with mutually enjoyable memories.

At breakfast the other day, we were trying to remember the signature tune at the end of dances. I hummed “Let Me Call You Sweetheart,” but it didn’t sound right. We paused a bit and then, in a low voice, Arlette came up with “Goodnight Sweetheart.” That’s it, of course, I said, and we both laughed as our thoughts went back to dimming lights at long-ago proms.

Small things, but—returning to journalism—what am I still doing here? Why are reporters interviewing me, video-recording me, turning our living room into a cinema studio? An Italian correspondent did a full page of me for the distinguished Turin newspaper La Stampa. He built it around the flash I sent to the Associated Press reporting the German surrender in Italy in World War II.

Fate, however, has me still standing.

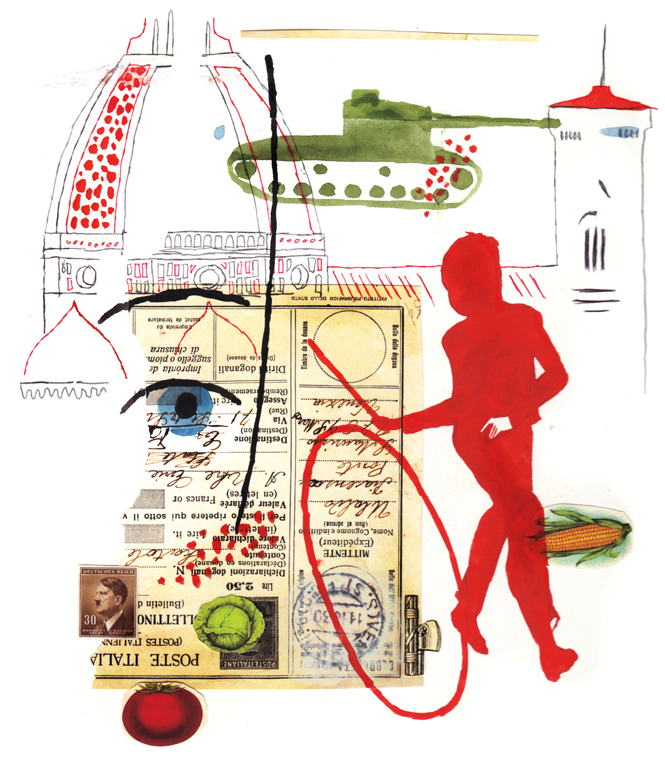

I saw the bullet-riddled bodies of Benito Mussolini and his mistress, Claretta Petacci, lying seminaked on the bare floor of an improvised morgue in Milan. Their self-proclaimed executioner was a Communist partisan leader with the nom de guerre of Col. Valerio. He told me that “Il Duce,” the vainglorious name of Mussolini in his heyday, died a coward, stuttering “but, but, but” and offering “an empire” to be spared.

Valerio said he had not meant to kill Claretta, but she threw herself in front of her lover and died in the machine gun bursts. The two had fallen into partisan hands while trying to escape to Switzerland aboard a German troop train. Their bodies and those of other slain Fascists were then hanged upside down at a Milan gasoline station in one of the war’s most macabre scenes of retribution.

Another event I’m interviewed about is the surrender of the Germans in Italy. The fighting there had faded in interest after the capture of Rome in June 1944 and the D-Day landings in France. Top news became the drive for Berlin. But fierce fighting continued up the Italian peninsula. And let’s remember that, from 1943 to the end in 1945, overall Allied casualties in Italy totaled about 320,000, and the Germans suffered about 336,650. Historians estimate that was the heaviest toll of infantry dead and wounded in the whole Western front.

As a kindergartner I had rolled a hoop in a Florence park. Who could imagine I would return to that same park in May 1945 to witness the German surrender? It took place in a big Quonset hut, with the overall commander, American Gen. Mark Clark, and the British, French and other Allied brass standing at the far end. The formal surrender had been signed a few days earlier, but this was the actual turnover of more than a million German troops to Allied control.

As a German general arrived with retinue, Gen. Clark’s little terrier dog, which somehow was loose, went snapping at the German’s high boots. The man stumbled a bit, but recovered. As he neared his Allied counterparts, I saw him hold out his hand. Was this a proffered handshake, some runic Prussian ritual? None of the Allied officers responded, however, and the hand just hung there for a long moment. Who among the Allied soldiery would have wanted to shake hands after that horrendous war?

It happened 70 years ago, and I was there.

George Bria ’38 is secretary of his Amherst class. He retired from the Associated Press in 1981 and lives in New York City. Illustration by Adam McCauley.