If you’re a journalist covering the presidential campaign, modesty and contrition are in order. Whether in the print, TV or digital realm, most of us have been so monumentally wrong so far.

The errors remind me of a semester back at Amherst when we read The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, by Thomas S. Kuhn. I was taken with how long people could be mistaken about such big and obvious changes around them. This time, the errors are less impactful on life around us but do include how Jeb Bush’s financial edge would make him pretty close to invincible. And how Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker was a formidable rival—remember that? Or how Sen. Bernie Sanders was an easy-to-ridicule leftie who could not possibly mount a vaguely credible campaign against Hillary Clinton.

Finally, of course, there was Donald Trump: Even if his early polling success was a surprise, he’d obviously be toast early; for example, he’d be history one news cycle after he made those nasty comments about Sen. John McCain’s Vietnam War record. Or claimed he saw thousands of Arabs in New Jersey celebrating the World Trade Center attacks.

No, no, no, no and no. But there have been many more analytical miscues. And they’re aggravated by polling that is increasingly untrustworthy because of poor response rates; decreasing levels of civic engagement among Americans; and overheated competition among media outlets, which can fabricate news in a Twitter-driven hothouse where speed is more a priority than precision. And feel free to throw in the occasionally negligible impact on some voters of actual facts. Trump’s standing in the polls did not budge after multiple reporters shredded his claims about those supposedly joyous Arabs on 9/11. It was part of a confounding pattern that underscored seeming media impotence: an outlandish statement, a torrent of press fact-checking to out an erroneous declaration and his subsequent jump in national polls.

“I share the shock of the punditocracy over the rise of Donald Trump,” says lawyer-author Scott Turow ’70. “To me, it emphasizes how profound the cultural divide is in the U.S. Black people keep telling me, with warrant, that I don’t understand their life experience, but it’s clear from Trump that there are plenty of white people who don’t perceive things in any way that remotely resembles mine. To me, he’s a flatulent, ego-mad blowhard, an ineffective public speaker who tends to free-associate disconnected drivel.”

Many who’ve observed what played out during the political realm’s endless spring training, in advance of February’s key tests in Iowa and New Hampshire, share Turow’s unease. But for at least one Amherst alumnus and political insider, it’s deflating but far short of a revelation, especially on the Republican side.

“I had a unique view,” says former U.S. Congressman Tom Davis ’71, a moderate Republican from Virginia whose wife ran for lieutenant governor in 2013. That year, he attended his party’s state nominating convention (where she lost). Even a pro like Davis was taken aback at how far the Republican base had moved.

“It’s a blue-collar party,” he says. “So when Bush announced, I said, ‘There is a Bush fatigue,’ and I didn’t think he could do it, even as the donor class flocked to him, thinking he was a winner. The right wing of the party, the antiestablishment, rural, non-college wing, had become the predominant force.”

Davis’ own former constituents in Fairfax County, Va., one of the wealthier areas in the nation, have drifted away from the Republican Party and become more independent. They certainly have little interest in Trump. The early surprise of the 2016 campaign, Trump has an allure that is especially strong among non-college-educated whites, according to various surveys and observers.

Davis, who heads the presidential campaign of Ohio Gov. John Kasich in Virginia, says his party might need a far-right candidate to win the primary and then lose the general election: “It’s the only way to get realignment. You could nominate somebody like a Kasich or [New Jersey Gov. Chris] Christie, and they could re-center the party. Or you could get somebody who gets defeated and gets you what the Republicans got with Barry Goldwater and the Democrats with George McGovern,” he says, alluding to overwhelming defeats—in 1964 and 1972, respectively—that led to a realignment in each party.

The impact of February’s big tests in Iowa and New Hampshire brought some clarity. But much remains unclear.

“To me, one of the most fascinating questions about the 2016 presidential campaign is whether the outcome of the race will hew more to demographic trends or historical trends,” says Steve Edwards ’93, a longtime journalist who is now executive director of the Institute of Politics at The University of Chicago.

“Voters tend to select presidents who offset the prevailing tendencies of the incumbent, not just in policy positions but in style and temperament.”

“It’s exceedingly rare for a two-term president to be succeeded by a member of his own party,” Edwards says. “It’s happened only once since World War II, when George H.W. Bush followed Ronald Reagan to the Oval Office. Voters tend to select presidents who offset the prevailing tendencies of the incumbent, not just in policy positions but in style and temperament. Think Nixon/Carter, Carter/Reagan, Bush/Obama. So one of the big questions facing Democrats is whether their party can put forth a nominee who can effectively navigate the remedy-versus-replica tension. It’s a tall order—and one that gives Republicans high hopes for 2016.”

On the flip side is the demographic challenge facing the Republicans. “The GOP enters 2016 having lost the popular vote in five out of the last six presidential elections,” Edwards says, “and most of the long-term demographic trends are running against them. As the U.S. becomes ever more multiracial, Republicans are a party increasingly dominated by old, white males. Democrats are cleaning up among the most rapidly growing demographic groups in the nation.”

Why does that matter? “There simply aren’t enough white voters around to drive Republican majorities in presidential election years, given turnout patterns.” Edwards notes these data points: In 1988, George H.W. Bush won 60 percent of the white vote and trounced Michael Dukakis in an electoral landslide. In 2012, Mitt Romney won 59 percent of the white vote and lost handily to Barack Obama. “In order to win back the White House, the Republican Party needs to do a much better job of appealing to people of color, especially among the rapidly growing Latino and Asian-American communities, and to connect with more single women and young voters.”

Will the electorate vote for an outsider? If you look at the big trends touching American politics—campaign finance, ideological polarization, apathy, partisan media and social media, among others—Trump doesn’t embody any of those changes in a meaningful fashion.

There is ample popular discontent. But there is no assurance that even with the rise of primary elections, the influence of political parties has become nonessential. There are establishments on both sides, and they will make themselves known with money, credibility and clout. On the Democratic side, they long ago cast their lot with Hillary Clinton. On the Republican side, they fumbled in the fall and early winter. Even as they did, there remained traditional realities of all presidential elections, namely the “fundamental question of economic performance and the public’s perception of the incumbent administration,” as Bowdoin political scientist Andrew Rudalevige reminds.

And yet, some wonder if we are in for real surprises. “I think this may be a year which is truly different, given the ways in which economic insecurity—especially for the white working class—is expressing itself through embracing the fear-driven politics of the GOP, especially Donald Trump,” says Thomas Dumm, the William H. Hastie ’25 Professor of Political Science at Amherst. “Anti-immigrant nativism and racism are getting injected into mainstream politics like no other time I can remember on the right. The New Left excesses of the Vietnam era were similar in extremism, but less deeply impactful on the overall politics of the country.”

Discussing the matter in advance of the Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary, Dumm felt the Big Question was clear: What would be the staying power of Donald Trump?

After all, nobody imagined we’d be mulling this in winter—certainly not my friends in the elite media.

James Warren ’74 is chief media correspondent for the Poynter Institute for Media Studies and a national columnist for U.S. News & World Report. He’s the former managing editor of the Chicago Tribune.

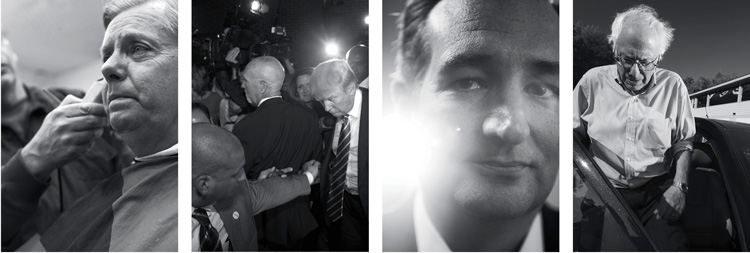

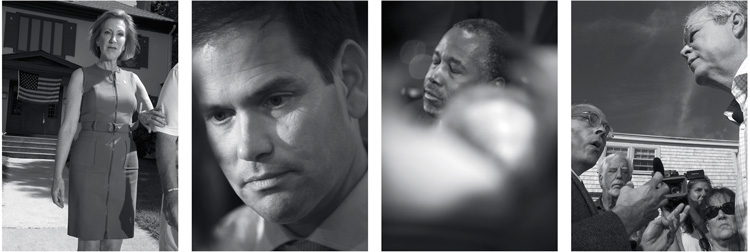

Photographs by Mark Ostow