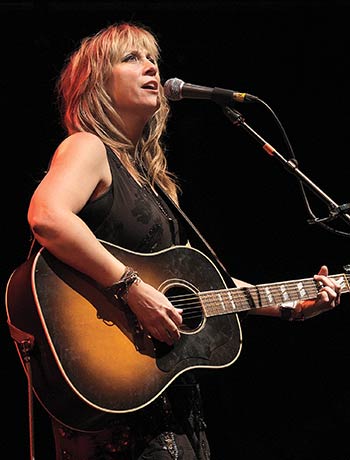

Ever since Judy Collins discovered Amy Speace, there’s been a lot of quality name-dropping. NPR marveled that the ’90 singer/songwriter’s “velvety, achy voice recalls an early Lucinda Williams.” Other critics have compared her to Rosanne Cash and Sheryl Crow. In the past 12 years, Speace has put out a half dozen folk/Americana albums, opened for Nanci Griffith and Mary Chapin Carpenter, relentlessly toured the States and Europe, worked with musicians tied to REM and the E Street Band, and become a darling of WFUV, New York’s cachet alternative radio station. The name-dropping even went meta when she opened for Pure Prairie League, and the band brought her onstage to help sing their 1972 hit “Amie.”

Remember that big, shimmery, harmonic line? “Amie, what you want to do?”

What Amy wanted to do was a lot.

So it was from the very beginning: “I’ll tell you, I was hungry,” she tells me over the phone, laughing at her younger self. (And just to clear up the pronunciation: it’s “peace” with an “s” in front, or, as one critic couldn’t resist: “Give Speace a chance.”)

I caught up with Speace on a sort of limbo day in March. She was waiting at her East Nashville home to hear if she could squeeze in minor oral surgery before leaving on a three-week European tour. Her rescue Redbone Coonhound, Flo, kept her company while her husband was out. (They’re newlyweds: Jamey Wood is a bluegrass musician.) In eight days, she’d be playing the Peyote Café in Milan,

followed by a dozen more gigs in Switzerland, Germany and the Netherlands, with the finale at a Haarlem venue, built in 1597, called De Waag (The Weigh House).

Weighing her own household of origin, this sounds like a pretty exotic life. “I mean, my father grew up dirt poor,” says Speace. “It took him eight years to get through university. He had to leave and work and leave and work.” She grew up in Williamsport, Pa., the oldest, with one sister and twin brothers. Their father sold window blinds. Their mother stayed home and then became a nurse. Today, her sister is a high-tech recruiter; one twin works for American Express, the other as an animal technician.

Speace is the cultural outlier in her family. At age 5, she started playing piano, later adding clarinet and tenor sax. She sang, danced, acted, wrote plays. In high school, she became the girl who got the leads in the musicals, thanks to her rooftop-powerful voice and theatrical chops. After 11th grade, an instructor at a summer program decided that Speace was destined to be an opera singer. Future sealed, she began auditioning for conservatories.

In opera, the cabaletta is the second part of a two-part aria. It’s always faster in tempo than the first part, and indeed, things turned accelerando for Speace—but in unexpected ways. It began with a member of the Williamsport school board, a Wellesley alumna, who saw something else, something broader in Speace. She suggested looking beyond conservatories to liberal arts colleges, and pointed her toward Mount Holyoke and Smith. The Speaces dutifully road-tripped their daughter to the Pioneer Valley. “I’d never even heard of Amherst College,” Speace confesses, but someone mentioned it was just up the road. Why not? They decided to take a look.

“It was sunny out, and there were these cool brick buildings and people were outside playing Frisbee and having a barbecue,” Speace recalled. “I’d gotten into the Eastman School of Music and visited it on a rainy day. All the students there wear scarves around their necks, and speak softly, to protect their voices. I looked at the people at Amherst and thought, ‘I want to be part of that crowd.’”

When Speace got to Amherst, though, the notes didn’t all fall into place. “I felt like I was coming in from a deficit,” she says. “I had slid through in my large public high school. But I got to college and thought, ‘Oh my God, these people have read Ulysses already.’”

Speace would go on to double major in English and theater and dance. She sang in the Sabrinas and starred, as a sophomore, as Johanna in Sweeney Todd. I asked Speace which professors made the biggest impact. “Barry O’Connell, Barry O’Connell, Barry O’Connell,” she joked in response, but she was serious. (O’Connell saw her in Sweeney Todd: “It was overwhelming—the sheer beauty of her voice.”) Her freshman year, she took this (now emeritus) English professor’s class on Southern literature. “I was doing really well in that class,” Speace remembers. “It was the first time I felt like my writing was getting better and better.” But her final paper, on the music of the civil rights movement, earned her the lowest grade of her college career.

O’Connell had called her out for writing from a place of unexamined white privilege. “It was so mortifying,” says Speace. “I avoided Barry my whole sophomore year. But my junior year, I went back and reread the paper and saw what he was pointing out, and I got it. I went to see him, fell apart and cried in his office.” That catharsis cleared the air. Speace took three more classes with O’Connell, who also steered her toward courses on Shakespeare, and he advised her for her senior thesis on Billie Holiday’s autobiography. “Everything I needed to learn about writing,” says Speace, “I learned from Barry.”

The day after she told me this story, she sent an impassioned follow-up email: “His pointing out the hard truth in my freshman year essay was one of those life events that, now, nearing 50, I am really grateful for,” she wrote. “These times in life when someone has the audacity to call you out, it’s like little revolutions, little moments that bring us to our knees and make us freak out, doubt ourselves, ask for help, and then get back up and try again.” The raw feeling in that statement reminded me of her go-for-broke lyrics. Just so: “As an artist now,” she continued, “I love these moments when the rug is pulled out from under me, because then I know chaos is upon me and that’s when real truth shows up.”

As graduation loomed, Speace wondered where that “real truth” would show up next. Andrew Parker, professor of English, suggested she try her luck with acting in New York City. Give it a few years, he said, and if it didn’t work out, he’d write her a recommendation for a Ph.D. program in English. Meanwhile, Peter Lobdell ’68, senior resident artist in the theater and dance department, put in a good word for her at the National Shakespeare Conservatory.

Speace went on to play many parts with the NSC and beyond: Queen Elizabeth from Richard III, Catherine from Henry V and Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing. She acted in off-off Broadway classical rep companies and did “guerrilla Shakespeare” in Lower East Side parking lots. She had an agent and she had auditions. But even when she landed parts, they paid peanuts: “Everyone was saying, ‘You’re really good,’ but not enough was happening.”

Then Speace bought a cheap guitar from an East Village pawn shop. Fresh off a “spectacularly terrible” breakup, she slept on a friend’s futon, listened to Leonard Cohen and wrote 10 songs in a week. “They were terrible,” she says. “But there was still something true in them.” Soon two friends asked her to sing at a benefit. She said yes, on the condition she could perform these new songs, and not covers. “I felt super shaky, because I was a terrible guitar player then. But something felt right standing up there at the mic. Like this was what I wanted to do with the rest of my life.”

Thus released, Speace started playing at New York folk clubs—The Bitter End, The Sidewalk Café, The Living Room. She still had one foot in acting, appearing in two forgettable young romance movies, 2000’s Chelsea’s Chappaqua and 2002’s Just Add Pepper. But music was taking the lead: In 2002, she self-financed and put out her first album, Fable.

Before I called up Speace, I spent a gratifying morning watching her on YouTube, and felt struck by the confidence in her presentation; her acting background lends gravitas, a sort of emotional anchor, to her voice. I praised her for this, but she brought up the downsides.

“When I first started folk singing, I had to kick the actor out,” she said. “I didn’t look shy on stage, so record producers would say, ‘You’re more musical theater or cabaret.’ This was the time of Shawn Colvin and Suzanne Vega. Radio-friendly, reedy voices with no vibrato: that was the sound.”

Speace describes her own voice as less like something from the reed section and more like a viola (critics have also compared her to Linda Ronstadt and Eva Cassidy), and that wasn’t cool at the time. “But I did have one person say ‘Just wait. It will come around.’ That was the person who discovered me and changed my life: Judy Collins.”