Image

Impressive—and Unsettling

I was disappointed to see the self-congratulatory note in Amherst magazine about the new Greenway Residences, which house 296 upperclassmen at a cost of $79 million (“New Dorms Integrate Academic, Social Life,” College Row, Fall 2016).

These dorms are stylish and impressive, and I’m sure students will love living there. Their construction, however, says something deeply unsettling about Amherst’s participation in a higher education arms race to build ever-more-luxurious housing, at eye-popping costs comparable to urban luxury high-rises. Per student housed, the Greenway Residences cost nearly $270,000. Per square foot, an astounding $710. Do we need a palace when comfortable dorms could be had for far less?

Amherst can afford these indulgences with the sixth-largest endowment per student in the United States, though one wonders whether some of this money could have been better spent on academics. While Amherst’s debt has reached higher-than-normal levels and the College has lost its AAA rating from Standard & Poor’s, its financial health and balance sheet are surely the envy of its peers. Moreover, to its continued credit, Amherst is need-blind and is one of few institutions to replace all loans with grants. The College’s pioneering work with QuestBridge is similarly laudable.

But Amherst’s actions do not occur in a vacuum. Less-generous private colleges and numerous publicly funded state universities have recently embarked on elaborate residential construction projects. These costs are borne partly by families through higher tuition, and often by the institutions through increased leverage and debt service, including, in Amherst’s case, its $150 million bond issue to provide bridge financing for the Greenway Projects, which caused Moody’s to place the College’s rating on negative outlook. Even when ostensibly funded by giving campaigns, society bears the cost through the tax subsidy provided by tax-deductible donations, and through tax exemption for higher education institutions.

By participating in this arms race, Amherst is contributing to the spiraling cost of higher education. Perhaps some leadership is in order.

Andrew Moin ’05

New York City

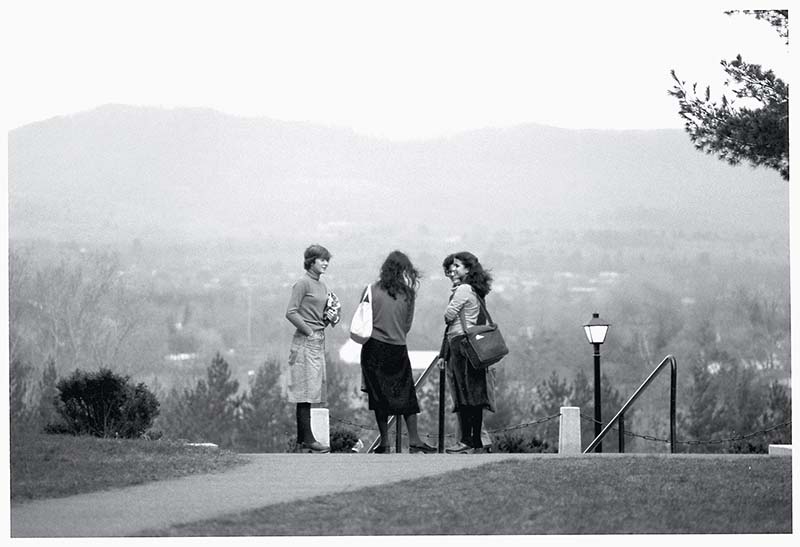

The People in the Photo

I am on the far left, and Janine Craane ’82 is facing me with the bag over her shoulder (“Hilltop View,” page 93, Fall 2016). Something is under my arm, most likely clothes for a daily team practice, as I am headed toward the gym. Or this could just be an impromptu meeting of The 1980s Clog Society–Memorial Hill outpost location. That jean skirt I am wearing was made/sewn in the car on my multiple visits to colleges my senior year in high school. It has since gone where custom-made denim skirts go to die. And should.—Kathleen Murphy ’82, New York City

Arkes and Natural Law

Entering Amherst as a junior transfer philosophy major, Arkes’ “Political Obligations” caught my eye. Classmates warned that Arkes would argue the immorality of abortion and the morality of the Vietnam War. I was ready!

As Professor Arkes spoke about self-evident “natural law,” I recognized the Socratic Method; if one accepted his initial premise, his conclusions would inexorably follow. I argued the existence of natural law was itself a premise, and not at all self-evident. After an hour of wrangling, Professor Arkes dismissed the class. After the second meeting, at which we had the same argument and result, I dropped the class.

While natural law may indeed exist, no human statement of natural law, truth or right is self-evident or immutable across time and culture. Seekers of natural law, right and truth can only make ever-better “descriptions,” as scientists do. By contrast, adherents of religious or other faiths often perceive their beliefs to be self-evident.

Arkes might have chosen religion as his field, rather than political science; “faith” better describes his convictions than “science.” Instead, he has tortured high ideals into tools of reactionary thought. Professor Arkes has retired, but his thinking has influenced our nation in ominous ways.

It is Professor Arkes’ privilege, as tenured faculty, to promote his particular “descriptions,” despite the fact that they are offensive to many in the College’s ever more diverse community.

The College, while bound to protect Arkes’ academic freedom, has lent active support to him, by sponsoring his organization, the Committee for the American Founding.

Professor Arkes has for many years exploited his position, and makes Amherst look like a bastion of reactionary thought.

Do Amherst students, faculty and alumni accept this? I do not.

I invite the community, especially Professor Arkes and President Martin, to respond.

Matt Rawdon ’79

Cumberland, Maine

That Was Amherst

Of the many valuable life lessons I learned at Amherst, one was from mathematics professor Robert Breusch, in 1953 (“Algebra: Not a Waste,” Voices, Summer 2016). I was a good, but not great, student as a freshman in his sophomore advanced calculus course. I was also a good but not great alpine ski racer and was in the infirmary recovering from a knee injury incurred in a race that weekend. Midweek, Professor Breusch appeared at my bedside with our textbook and note paper. He said, in his heavy German accent, “Larry, you are too good a student to fall behind in your studies,” and coached me through two weeks of lessons. I went on to win Amherst’s Walker Prize in Mathematics, and I still regret that I did not use part of the $100 prize on a gift for him. I went on to a career of teaching engineering at MIT for more than a half century, during which I constantly try to show my students the same personal attention that I received in the infirmary in 1953. That was Amherst.

Laurence R. Young ’56

Cambridge, Mass.