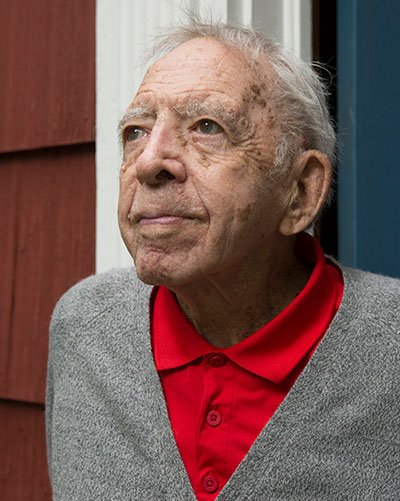

We spent a couple of hours together in the modest home where he and his beloved late wife, Josephine, raised their five children. It’s painted barn red and chocked up with books, keepsakes and old photos—but new photos, too. There he is, at age 102, in a kayak. See him at 97, in a hot air balloon with his lady friend (a birthday gift for her 80th). At age 96, he climbed to the top of the Statue of Liberty. “Old age,” wrote Cicero, is “the crown of life.” Mr. Watts wears it well.

I put many questions to Amherst’s most senior alumnus that day, asking if he needed breaks (he never did), and we paged through the

Olio and bound volumes of

The Amherst Student from 1931 to 1935. He was alert throughout, correctly recalling details and dates to a flabbergasting degree. He stood, slowly but unassisted, to greet me. Hearing was his only difficulty. Robin Santoianni, his youngest child, repeated some of my queries by speaking loudly into his left ear, and helped facilitate our exchange with grace and wit. She joked that her main job, these days, is acting as her dad’s press agent.

The first thing to know about Gardner Watts is that, like so many Amherst men before him, he is a minister’s son. Henry Watts served in several Presbyterian parishes. Audrey Watts was energetic in civic affairs. They had three sons, with Gardner the oldest. One of his father’s positions landed the family in Sacramento, Calif., and there the boy, it seems, was imprinted by the drama of history as it happens. This was in 1919, and he was 4. He came upon the reverend, who was holding a newspaper and on the verge of tears: “I said, ‘Daddy, what’s the matter?’ I remember my mother said, ‘A great man has died back in the east.’ ”

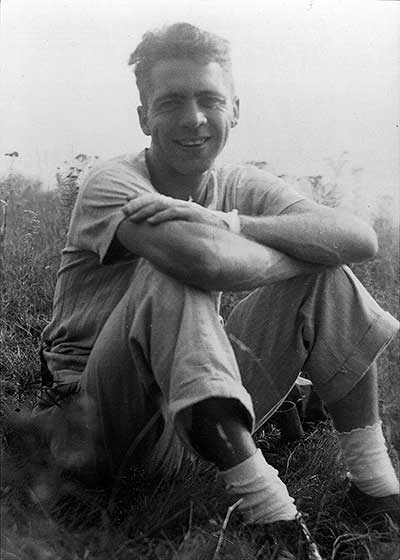

That great man was Theodore Roosevelt. Today, this president’s picture hangs in the house here in Suffern. During our interview, I asked Watts what person, past or present, he’d most like to interview. He immediately said it was TR. The two men diverge in temperament—Watts describes himself as an introvert—but both have shared a deep love of history and the outdoors. Roosevelt was a robust booster of the Boy Scouts, and Watts began his lifelong habit of hiking the nearby Ramapo Mountains as a member of Suffern’s Troop 21.

At age 15, he and another scout were deployed to Suffern Presbyterian, the Rev. Watts’ church, to escort a frail elderly man at a Memorial Day service. He was a Civil War veteran in full uniform, agedly resplendent in Union blue and the buff silk sash of a general. “He had marched with Sherman, I found out later,” says Watts, who also has Civil War servicemen in his family tree. “For an hour and a half, I held his arm and hand. That made a great impression on me.”

His youngest child jokes that her main job, these days, is acting as her father’s press agent.

In high school, Watts had one of those teachers who shifts everything. She taught history with verve, and her name was Mrs. Wanamaker, a Mount Holyoke graduate who encouraged her shy student to think of a top college. He got into Wesleyan and Amherst and chose Amherst for its stellar history department—he’d known he wanted to teach the subject since taking her class. Also because Amherst gave him a scholarship, and said he could work on campus to earn more.

In the wake of the 1929 stock market crash, the College had considerably and creatively ramped up what might be called early financial aid—paying students for kitchen labor, jobs in the library, felling old campus trees, selling tickets at sporting events, doing whatever could be hired out. This was because so many families had fallen on hard times. Indeed, when Watts entered Amherst, it was 1931, the pith of the Depression. With his flock too broke to pay his salary, Henry Watts had just lost his position. A distant relative stepped in to keep the family going, but there was nothing extra.

After joining the other first-year New Yorkers on the train to the Valley, Watts arrived on campus and pledged Delta Tau Delta, because it was open to letting him pay his room and board by doing dishes and waiting tables in-house.

Between sudsing and studying, Watts didn’t have time for much else. He did play on the tennis team a few years, and occasionally played piano in his fraternity house. He recalls the inevitable freshman hazing: being kidnapped and blindfolded one night and dropped somewhere on campus. (“I remember the cold.”) He liked the theater, and enjoyed a couple of student productions: The Emperor Jones and Berkeley Square.

Come summertime, Watts needed to stoke up more earnings to help himself and his family. He got a $26-a-month job on a steamship in 1933, and in 1934 he worked in the engine room of a passenger ship—the SS Theodore Roosevelt, no less—sailing to Europe. That August, as they docked in Hamburg, he and a shipmate were given three days’ shore leave.

What happened next, naturally, he put in a resonant historical framework: “It was the same month that President von Hindenburg died, and Hitler was seizing power. I saw the Nazi parades, and all the Hitler books in the stores. We were just wandering down the streets, and suddenly we were accosted by a policeman. He marched us down to a police station. I’m sure we were confused, quite frightened—it all happened pretty quickly. They shouted at us, kept us for a few hours. Then they released us. We found out we had crossed the street illegally, just jaywalking. So I was arrested in Germany. In Hitler’s day. I guess it’s a story worth telling.”

I guess it is.