An adage holds that victors write history. Actually, evidence writes history, and new evidence demands new narratives. But what do we mean by evidence? Associate Professor Lisa Brooks opens her sweeping new look at King Philip’s War with thoughts on what Jacques Derrida called “absence of presence.” How does one do justice to the “absent”? We must recover their voices to write what Jean O’Brien called “replacement narratives.”

Brooks knows that sometimes absence of presence means scholars haven’t looked in the right places. In her meticulously researched and imaginative Our Beloved Kin, Brooks spends time (in her words) “reading in the archive,” but also “reading scenarios” and “reading the land as archive.”

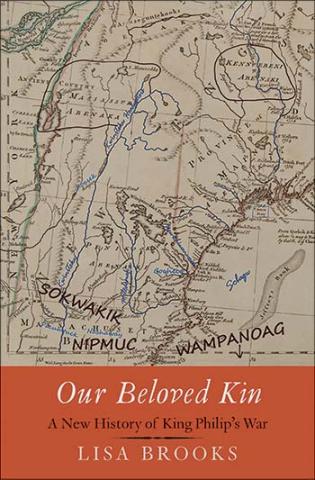

Hers is a creative mix of history, speculative (and often poetic) impressions of the minds of historical actors and inferential archaeology derived from perambulations of the sites where 17th-century events unfolded. She admits it’s a complicated story and intersperses grounding maps throughout the book.

The core of Brooks’ gendered and racialized look at King Philip’s War shines through the intersections of three biographies: Weetamoo, a powerful female Wampanoag sachem; James Printer (Wowaus), a Nipmuc and 1662 graduate of the Harvard Indian College; and Mary Rowlandson, who penned a famed account of her 1676 captivity.

Not even the notion of English ‘victory’ was entirely true.

A capsule view of King Philip’s War holds that it began in 1675, when the Wampanoag sachem Metacom (also known as Philip), disgusted by several years of humiliation at the hands of Plymouth colonists, unified various Algonquian tribes to exact revenge. The conflict evolved into a New England-wide war that raged until late summer 1676, when Metacom was killed and residual fires were quelled. The war was short but bloody, with dozens of English settlements destroyed, nearly half attacked and about 10 percent of the region’s white male population killed. Many historians mark its end as the point at which Indian New England became European.

Brooks agrees that the survival of the English Northeast was by no means a given in 1675. New England was beset by all manner of challenges, including ill-functioning colonies, spillover from political turmoil in England, declining religious piety, colonial land hunger and colonial propensity for violence. The latter two are the focus of Brooks’ account as filtered through Native eyes. Through this frame, iconized English pioneers become land thieves, treaty-breakers, racists, murderers and enslavers. Brooks finds few cases in which Natives precipitated violence, but plenty in which Englishmen broke promises in order to assert their interpretations of justice and God’s will. Even Printer was nearly hanged.

Brooks’ boldest iconoclasm is her reinterpretation of Mary Rowlandson’s narrative. Rowlandson criticized Weetamoo, her captor, for failing to act as an English woman. Weetamoo, in turn, found Rowlandson sniveling, vain and selfish—unlike an Algonquian woman. Both lost children on their mutual sojourn, but Rowlandson could not see “the space of motherhood where the two women’s lives intersected, where condolence might have fostered understanding. In one sense, she simply could not accept that an Indian would feel the same emotions as a real human being like herself.”

There is little in Brooks’ book that evokes pride for English ancestors. Hers is a story of unspeakable violence, innocents hanged, allies betrayed and enslaved, and murder under the pretext of negotiation. Not even the notion of English “victory” was entirely true; war lingered in the north until the 1678 Treaty of Casco Bay ended hostilities largely on terms dictated by the Wabanaki.

Our Beloved Kin took me back to undergraduate days and the deep shame experienced when reading of Great Plains Indian wars in Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. Our Beloved Kin is prelude to such injustices, and James Printer’s life a tragic foreshadowing. He lived until 1709, and I can’t imagine what went through his mind as he recalled the events of 30 years prior.

But I’ll bet Professor Brooks can.

Weir, recently retired from UMass Amherst, is the author or editor of seven volumes of U.S. social history.