Our narrator, Ivan Link, is a professor of philosophy at a small liberal arts college. Ivan is out to solve the Gettier Problem, an epistemological paradox named for Edmund Gettier, who formulated it in a 1963 paper. As summarized by Ivan, the problem suggests “a belief can be justified and true, but still fall short of knowledge.” Ivan has spent 10 years writing a monograph on the subject, which makes it all the more comical to watch him fail to identify situations in his own life that illustrate the Gettier Problem exactly. The result is a terrible and embarrassing disaster. Could it be that knowledge needs something more in order to be Knowledge?

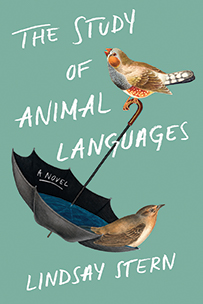

Prue, his wife, is a biolinguist and rising star in academia, with five times more published work than her husband (a secret sore point for Ivan). She is up for tenure and has recently conducted a promising experiment on finches. The results have left her uncertain that we humans are really able to Know anything, especially where beings other than ourselves are concerned. For example, when we conduct experiments in which crows demonstrate an ability to overcome spatial obstacles and arrive at food, have we shown that crows are intelligent, or have we made them mimic human behavior? If the latter, how can we ever hope to overcome anthropomorphizing animals and understand what they Know as they know it?