April 11, 1945. Nordhausen, Germany. Thayer Greene and his regiment had been tapped to scout out the small city. Greene was among the lead scouts. He had been in combat for less than 100 days, and he was 19 years old.

Greene knew he would be joining this war; all his contemporaries knew it. He had thought he was ready. In high school, he had purposely studied German as one of his foreign languages, and in September 1944, he boarded a train to Fort Devens to enlist. Upon arrival, he had made his case: he knew German, he was a bright guy. Wasn’t he a good fit for army intelligence? The stony-faced corporal listened to Greene, stared back at him for a moment, then asked, “You got flat feet, bud?” Greene was placed in infantry—Third Armored Division. Off he went to a whirlwind basic training course, cut to nine weeks, down from its usual 13, so that he could be sent off to the front.

Up to this point, Greene’s short experience in the infantry had been at times numbing, at times even dull. There had been long hours of waiting, waiting, waiting for something to happen, punctuated by moments of high terror in combat. Now he was on high alert. Perhaps his high school German did count for something; he had been sent to Europe, not the Pacific, and now he was here, outside the small city of Nordhausen. His infantry platoon had been sent to take the city, and he and his fellow soldiers had assumed the enemy—the Germans—would be waiting to stop their attack. Their platoon was to lead the attack and engage the dug-in troops.

Greene and half a dozen other soldiers soundlessly entered the perimeter of the city. They remained low to the ground, as they had been trained—in some cases, like Greene, merely months prior—in order to dodge machine gun fire. “I was ducking and weaving, taking cover,” he recalls. Looking at Greene, a tall, long-limbed man with sparkly blue eyes that crinkle with humor, one can easily imagine him as an impish 19-year-old boy. Now, however, as he entered the city, Greene was alert and serious, prepared to meet with a rain of artillery at any moment.

But... none came. “I was hiding behind a stone building,” he says, “peeking around the edge.” Finally, the stillness of the city allowed him to let down his guard just enough to step around the building and look into the distance. He saw someone, far off on the horizon. Greene raised his rifle and aimed.

The man was making his way toward Greene, but slowly, haltingly. As he came closer, Greene saw that he was unarmed, and lowered his own rifle. He also realized the man was in uniform, but it was a uniform he didn’t recognize. “It was white with black stripes,” Greene recalls. “And it was just this one man. He was a walking skeleton.” The man came closer; Greene continued to watch him, waiting for something about this scenario to make sense. The man had to realize Greene was an American soldier; he could see Greene’s rifle. Why was he continuing to approach? “He staggered up and fell to his knees before me, uttering, ‘Freiheit. Freiheit.’”

Freedom. Freedom.

Greene was learning that he was among the first of his troop to stumble upon the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp, known to historians as one of the most brutal. German soldiers had already abandoned not only the camp but the entire town, which Greene’s regiment now overtook without struggle. The man at Greene’s feet had glazed eyes, and his bones stuck out alarmingly. “Zu essen?” Greene asked him with his simple German, offering him some of his army rations. “Nein,” the man said. “Tod.” No. Death. (The man was right. When medics arrived a couple of hours later, they confirmed it for Greene. “If you feed these starving humans,” they said, “you’ll kill them. We’ll make them a nourishing broth.”)

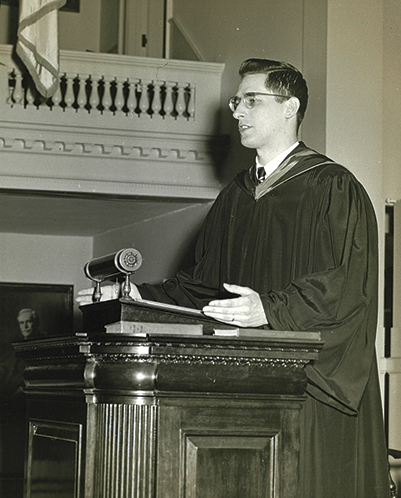

Going into the ministry may have been Greene’s

saving grace, but not in the way one would expect.

A mile into the city, Greene and his fellow scouts found the camp the man had staggered away from. It was inhabited by a few hundred half-alive inmates, all wearing the same striped uniform. They were mostly Russian prisoners of war, and by the time Greene and others found them, they were outnumbered by about 1,300 corpses stacked two or three bodies high. “Some of the inmates were walking and talking,” Greene says, “but many were not. ‘Ich bin Amerikanisch,’ we told them, but they were overwhelmed.” So was Greene. He was still, after all, a teenage boy, and this moment, “a scene of abysmal evil,” would follow him for the rest of his life.

Decades later, in group therapy, Greene would begin processing the trauma of merely witnessing the horror. But that night he wrote to his parents back in Connecticut, where his father, Theodore Greene ’13, awoke each morning for his post as a Congregational minister, day in and day out, just as his grandfathers, Lucius Thayer and Frederick Greene, both class of 1882, had done before that. How did the hopeful gospel that his father and grandfathers preached have anything to do with the world Greene now inhabited? None of them had gone to war. “I wanted my family to know what compelled me to kill Germans,” Greene says fiercely. “Because, up to that point, the war was so impersonal. But when I saw what I saw that day, I said, ‘We have to defeat them. We have to defeat them so that fewer people die.’”