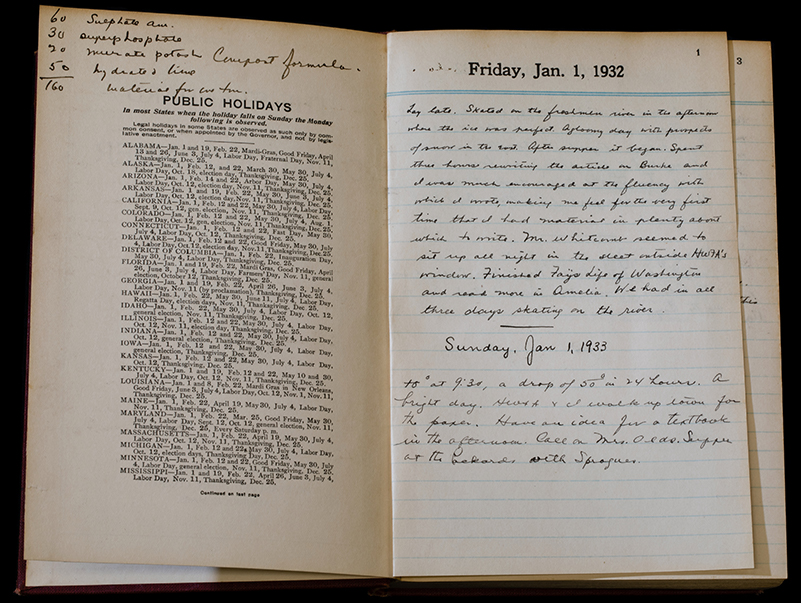

While teaching four decades of Amherst freshmen how to write, Theodore Baird seldom published his own work, but he wrote every day in his journal.

It’s been more than a half-century since Baird’s English 1–2 composition course—which challenged, inspired and mystified students—went the way of other core requirements. In a fitting epilogue to the career of an instructor whose personality was especially intertwined with his teaching, the College’s Archives and Special Collections has acquired 60 years of private diaries kept by Baird and his wife, Frances, known as Bertie.

Earlier this year, Tom Fels ’67, one of Baird’s students, left Paula and Walter Auclair’s farmstead in Pittstown, N.Y., his Subaru Outback filled with old composition books and binders of pages penned by the Bairds, Amherst-bound. Paula Auclair had inherited them from her mother, Alice Machlett, Bertie Baird’s sister, who’d received them after the Bairds’ deaths in February and December of 1996. She felt it was time for the diaries to return to Amherst.

He judged the ice on New Year’s Day “perfect” for skating, but the weather was “gloomy.”

Ted Baird taught at Amherst from 1927 to 1969, and Bertie was a Smith professor for several years. They lived on Shays Street, in a home they commissioned from Frank Lloyd Wright in 1940, the only Wright house in Massachusetts.

The diaries, amounting to some 21 linear feet of material, have tripled the amount of Baird-related text in the College archives, joining correspondence between Baird and his students and colleagues, some curricular materials, and manuscripts published and unpublished.

Archives intern Elliott Hadwin ’19 got to know the Bairds throughout the spring, vacuuming decades of dust from many of the volumes and filing them in chronological order, learning little bits about the couple as he made his way. “They are writing every single day, together,” Hadwin says. “You get an idea of how different their lives are. He, as an Amherst professor, gets to be a little more up in the clouds,” while his wife was more focused on the practical side.

The diaries include accounts of Robert Frost. Among the few news clippings in the diaries is a June 17, 1938, article from The Amherst Student about Frost’s resignation from the Amherst faculty following the death of his wife, Elinor.