Think only of the past as its remembrance gives you pleasure.

—Elizabeth Bennett, Pride and Prejudice

This article is adapted from a longer one that appears in the latest issue of the Amherst literary magazine The Common. Read it, and learn more about The Common, at thecommononline.org. That essay is in turn adapted from Marietta Pritchard’s book Travels with Bill (Impress, 2018).

We don’t travel as a couple anymore, Bill and I, except for the shortest jaunts to Boston maybe once a year, in the summer to the Adirondacks to visit Bill’s brother and family, and to the Berkshires, where friends sometimes take us to indoor concerts at Tanglewood (Bill doesn’t listen to music outdoors). So I travel on my own, but more and more rarely: day trips with a friend, twice-yearly visits to Oregon to keep in touch with son Will and family, once a year or so to the Washington, D.C., area to see my sister, rare overnights to New York. I also dig in more closely here at home—not as closely as Bill does with his piles of books and constant reviewing and teaching at Amherst, but still, closely.

I walk, usually with the dog, and enjoy the local scene, one that changes with every quirk in the weather, time of day, seasonal decoration, home improvement and new retail shop. I make small alterations in the routes we take—one day more sidewalk, another day more woods, more open fields. I’m not as restless as I once was, it seems, not so much yearning to travel, not so much yearning of any sort. Unlike the dog, I no longer ache to break through fences. My daily round seems to be enough.

Nobody wants to hear about your trip.

—Amherst College Professor of English Theodore Baird

For my parents—my father born in Budapest in 1895, my mother in Vienna in 1907—travel was an expression of their wish to see the world, but also of their status as cultured, leisured people. Married in Budapest in 1931, they went on their honeymoon to Italy and to the Dalmatian coast of Croatia. They had a car with a chauffeur, stayed in good hotels, ate well. In the photo albums I have of the first years of their marriage, there are many shots of monuments and churches, of my mother, always fashionably dressed, standing in front of one or another of these locations.

After they—we: my parents, my sister and I—came to the U.S. in 1939 and settled in Scarsdale, N.Y., my parents traveled little. As “enemy aliens”—Hungary had become an ally of Germany—they couldn’t easily leave the country. They had little interest in getting to know the States, and besides, there was gas rationing. They avoided Central Europe until the early 1960s, when they made a brief visit to Austria and Hungary. My father was reluctant to return to his home country, which was now under Communist rule. No family members remained there; all had emigrated or perished. But my mother wanted, as she said, “to draw a line under it.”

The experience was unpleasant. People were remote and formal. My father was convinced that their hotel room was bugged, and perhaps it was. The line my mother wanted was drawn, hard and fast. My parents never went back to Hungary after that, and I heard my father speak about it only once, when he was quite old. “It was a beautiful country,” he said, and there were tears in his eyes.

Between 1964 and 1974, Bill and I and our sons spent three separate sabbatical years abroad: Rome once, and London twice. For quite a few years afterward, Bill and I traveled together in the summer, back to England, back to Italy and then to France, where I wanted to follow the fatal trajectory of my Austrian grandfather, who died there at the hands of the Nazis in 1943.

Then, about a dozen years ago, Bill decided he did not want to travel anymore. I see the decision beginning with a diagnosis and treatment for prostate cancer, which put him in touch with his mortality in a new way. He was also beginning to have trouble with his back—not excruciating, but steady, chronic discomfort. Sitting in a car or an airplane for long periods was, to put it mildly, no fun. All of this appeared to concentrate his mind. From here on, he seemed to say, he would spend his time and energy reading, writing and teaching, listening to music and enjoying the meals in his kitchen, with me and sometimes with friends and family. No longer willing to drive to Boston to attend the basketball games in the now impossibly loud and expensive Garden, he would watch on TV as the Celtics’ fortunes rose and fell. He would enjoy visits from his sons and grandchildren, staying home to keep our corgi company while I periodically went to visit them and sometimes ventured even farther afield.

Recently, in an effort to get straight about our mutual and separate timelines (“What was the year we stayed in that funny inn in Cromer on the North Sea?”), Bill handed me the typed journals he’s kept of some of his and our travels over the years. I have kept my own journals, and the records we wrote separately have come to represent for me not only accounts of our varied, often shared experiences, but also, in some larger way, our points of similarity and difference. I see them in combination as a portrait—a collage, a mosaic, a diptych—of our 60-year-plus marriage.

What happens when two people live together for decades? Over time, it seems to me, some differences get worn away, while some remain like old scars that ache when it rains. All marriages are mixed marriages, I once asserted, and almost all battles can be boiled down to the irritable question: “Why can’t you be more like me?” On the other hand, if one is lucky, there is the balm of affection and shared interests. In addition, there is the huge volume of shared experience, private jokes, catchphrases. Bill and I can finish each other’s sentences, anticipate each other’s responses. Great satisfaction can be found in this lifelong dance, this not always graceful pas de deux.

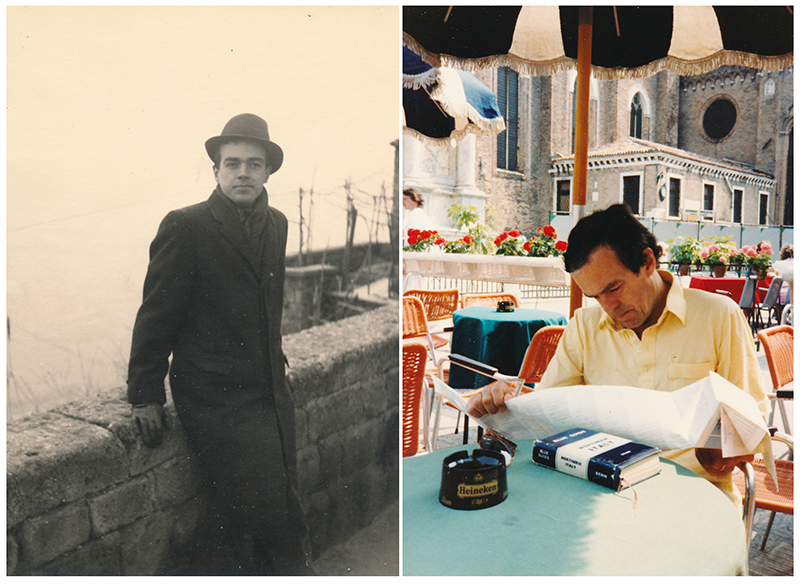

Above left: Bill poses in an Italian hat and American topcoat on a chilly day in Orvieto, Italy, during the couple’s first sabbatical year abroad, in 1964. “The year was a struggle to survive as a parent and wife,” Marietta writes.

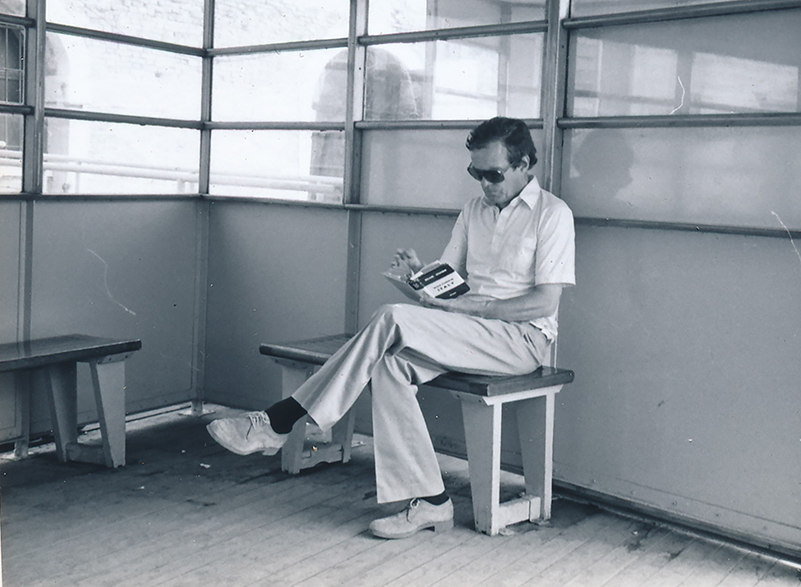

Above right and below: For Bill, if it wasn’t in the guidebook, it probably wasn’t worth seeing. Marietta writes, “He often quoted its severe opinions. ‘A not very impressive ravine’ was one of our favorites.”