Last September, I visited Berlin to participate in the Internationales Literaturfestival Berlin and spent my four days there trying to reconcile that city, that country of friendly people, with the atrocities of the Holocaust. What an out-of-body experience it was to walk those streets and think: here, here is where they did it. How, I wondered, did a whole nation of ordinary people like you and me transform into a murderous machine that vanished 6 million human beings? In Wunderland we discover that the answer lies in looking very closely at individuals and their delusions.

When we first encounter Ilse and Renate walking arm in arm down the Unter den Linden, they are just beginning to notice the distinctions emerging in Hitler’s Germany. Rebellious and adventurous Ilse , desiring to be part of something bigger than herself, joins the girls’ league of Hitler Youth. Renate is more interested in the affections of Rudi Gerhardt, a handsome and popular Hitler Youth, even if his reverence for Mein Kampf makes her uncomfortable. Besides, she knows her parents will never give her permission to join the league, because they loathe Hitler and his politics. She feels left behind as Ilse gets more and more involved in the league. Together, they devise a risky plan to get Renate in, unaware that they are about to uncover a secret that will tear them apart.

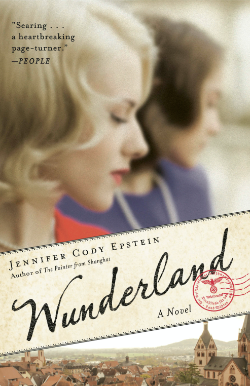

Wunderland

By Jennifer Cody Epstein ’88

Ballantine Books

Thrown off on different trajectories, both women come to know crushing fear. Ilse fears the men who surround her, even as she perseveres in writing propaganda for the German state. For many years after the war, she will live in fear of discovery and condemnation by her daughter, Ava. Renate, meanwhile, fears dissolution as she watches her mother pay every price possible to keep their family together and her father descend into silent stupor. She describes her parents as “not unlike those dead stars ... They go about their lives … sending out the impression of still being fully living, engaged human beings. The truth, though, is that they are simply sending out ghostly light into space... .”

Through Ilse , we experience the misguided idealism of the German people under Hitler and their inability to discern what they were becoming. She will spend her life hiding from Ava’s demands for truth. In this case, the sins of the mother are indeed visited on the child: Ava, like many of her generation, will make terrible mistakes because of her inherited guilt.

And through Renate and her family, we come to understand the danger of being spectators in the world, of failing to confront what disturbs the conscience in the false hope that it will simply go away. It won’t. Because although Wunderland concerns itself with events of long ago, it is very much a novel of our moment. As the Rohingya in Myanmar and the Uighur in China face persecution because of their religious faith, and in these times of xenophobic nationalism in the United States and Europe, Wunderland is a stern reminder of just how easily you and I can become inhumane or be made inhuman.

It is a stern reminder of how easily you and I can become inhumane or be made inhuman.

Emotionally, the novel is a tough read. Innocent people die brutal deaths. Perpetrators brook no negotiation. We watch the beautiful, historical synagogues of Berlin burn. All of humanity’s cruelty is on display. But we who are distant from the horrors of the past have an obligation to witness the terrible things that have happened to others. We owe it to them to not look away, to remember, to weep and to no longer spectate.

Epstein builds her novel as carefully as one would a monument. With three point-of-view characters and using two tenses, she risks losing her readers from chapter to chapter, but this does not occur, because she is a master at pacing. The novel peels like an onion, revealing a daughter’s decades of longing for a small window into her mother’s mind; loves gained and lost even before they bloom; the comfort of friendship and the desolation that comes when one has not a single friend left in the world; the impossibility of ever returning from some decisions; and the fact that even after world-ending catastrophes, we must get up and continue living.

Wunderland is a dirge; it is a love song; it is condemnation; it is atonement; it is a fresh, bleeding wound; it is a scab; it is a knot of hot anger and regret; it is hope and the beginning of an almost impossible forgiveness.

Epstein, the author of two previous novels, double-majored in English and Asian studies.

Photo by Julie Brown