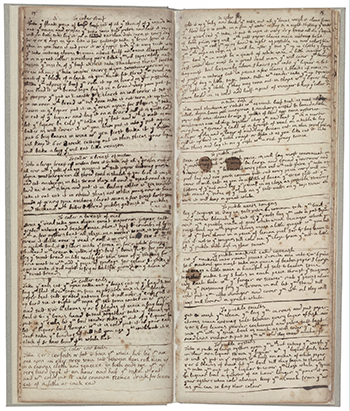

Nine students transcribed, edited and adapted

recipes from the mysterious Mrs. Knight, whose

handwritten collection they examined from

multiple angles.

We don't know who Mrs. Knight was, but we know she liked to cook.

Her 102-page, 400-recipe manuscript, circa 1740, got the Amherst treatment this January, as nine students studied the handwritten collection of recipes and folk remedies from every angle. They considered trade routes. They researched availability of ingredients. They learned about “implicit knowledge”—and what happens when someone doesn’t have it. And then they adapted and cooked some of the recipes.

The manuscript was on loan from the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. Every year, during interterm, the College sends a small group of student fellows to conduct research at the Amherst-owned library, founded by Henry Clay Folger, class of 1879, and his wife, Emily. But this year was different. The Folger had just closed its doors to the public for a major multiyear renovation.

“We wanted to keep the fellowship alive during our intermission, and we thought the best way we could do that was by coming to Amherst,” says Heather Wolfe ’92, the Folger’s curator of manuscripts and a former English major at Amherst.

Manuscript in hand, Wolfe and a colleague traveled to campus, booked a prep kitchen in Valentine and, with the student fellows, got to work.

“I’m totally inexperienced at cooking, and this is the most bizarre entryway into it,” said Olivia Gieger ’21 as she prepared “Extraordinary Plumb Cake” in Valentine. The recipe calls for not a single plum. It does include currants, citrus peels, nutmeg and cloves, as well as a note from Mrs. Knight that it “was given by the nicest housewife in England and it’s as good as it’s ever made.”

Among the book’s other gems are instructions on how “to burn Butter,” prepare “pigeons Transmogrified” and “Fry Lambstones and sweetbreads.” Alongside such recipes are cures for shortness of breath, cancer and “joint evil.”

While whipping up meringue frosting for the plumb cake, Amanda Herbert, the Folger’s associate director for fellowships, gave advice on how to read between the lines: “Recipe books are filled with what we call implicit knowledge,” she said, with authors of the era assuming, for example, that everyone already knew how to bake bread or pluck a chicken or mix dough. The students also discovered recipes that were imprecise or unrealistic about amounts and temperature. The plum cake is a prime example: it calls for 7 pounds of flour. As Herbert noted, “That would make a massive plum cake. Also, eggs were smaller in the 17th and 18th centuries. So when we use eggs in recipes, we usually reduce them—two-thirds of what the recipe would call for.”

As Herbert and Gieger prepared the cake, Sarah Montoya ’21, a self-described “recovering vegetarian,” crafted “forced meat”—which is basically meatballs. She ended up tweaking the original recipe, which requires, among other ingredients, veal, anchovies and a pound of suet.

Meanwhile, Liam Downing ’21E—who, during breaks, works at his family’s restaurant in Manchester, N.H.—cooked a recipe more recognizable to 21st-century palates: French rolls stuffed with lobster salad. Students noted that during Mrs. Knight’s time, lobster was a poverty food, being in plentiful supply in Europe and New England.

When they weren’t cooking, students talked with faculty and studied old books in the College Archives. The program also benefitted from field trips to Historic Deerfield and the College’s own Book & Plow Farm, Wolfe says.

“And we have this amazing kitchen,” she adds. “We don’t have a place like that at the Folger.”

Bill Sweet is a news writer at Amherst.

Photos by Adam Detour & Jiayi Lu

Styling by Christina Barber-Just