Above: Catherine Newman ’90 is the author of four other books, and is also the etiquette columnist at Real Simple.

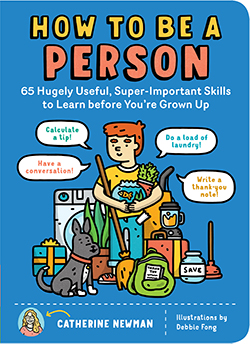

Below: How to Be a Person: 65 Hugely Useful, Super-Important Skills to Learn Before You’re Grown Up

By Catherine Newman ’90, with illustrations by Debbie Fong

Storey Publishing

“I was looking at this book,” said 8-year-old Asa, “and there’s a part about how to tie a necktie. Why is that in there? Why would I want to learn that?”

I faced my nephew—who’d recently had his hair dyed blue and was lounging with his sock-clad feet dangling over the arm of his grandparents’ armchair—and said sincerely, “Well, someday you might have to wear a tie to some fancy event.”

“Oh, yeah,” he said, also sincerely, as if just imagining it for the first time. “I might have to do that.”

Practical things that young people might, or will almost certainly, have to do someday are the subject of Catherine Newman ’90’s How to Be a Person: 65 Hugely Useful, Super-Important Skills to Learn Before You’re Grown Up. I was eager to show the book to my nephews and their parents, having long ago turned them on to Newman’s writing both about and for kids. Her fiction writing workshop was one of my favorite courses at Amherst, and hers was the only parenting blog that I, as a non-parent, have ever read extensively.

Asa’s 10-year-old brother, Ewan, devoured all 160 pages of How to Be a Person within a few hours (as he’d done the previous year with Newman’s middle-grade novel One Mixed-Up Night). Though he claimed he already knew how to do many of the tasks described—tie various kinds of knots, write thank-you notes, take care of his cat—Ewan said the book might inspire him to actually start doing them more often.

“It just had a lot of stuff in it that was easier to understand than when my mom’s yelling at me,” he said.

His mom—my sister, Rebecca, an elementary-and middle-school psychologist—laughed and agreed about the book’s advice: “I think it’s better-received from someone who is not Mom, and who has a better sense of humor than Mom.”

Newman’s own way of phrasing this, in the introduction, is that the book tries to help kids “step toward [responsibilities] with confidence rather than being backed into them by that bulldozer of nagging otherwise known as your mom or dad.”

I would have loved this book back in the ’90s, not only as a child who strove constantly to prove myself smart, mature and independent, but also as an aspiring writer, comedian and cartoonist. There are pop quizzes throughout that are easy to ace, as well as nods to scientific evidence to back up the tips (“Neuroscientists at the National Institutes of Health have used neural imaging to show that acts of generosity light up the pleasure and reward centers in your brain…”). Newman relishes similes, my favorite of which, here, describes how batteries should be “arranged in alternating directions, like a group of cousins sleeping head-to-toe in a bed.” And Debbie Fong’s many friendly illustrations make use of bold lines, shapely shadows and speech bubbles. I laughed out loud at the illustration of How to Fill Out a Form: The fictional form-filler-outer is one “Heywood Yapinchme” from “11 Pickle Parkway” in Slickpoo, Idaho—which, OMG, I’ve just now Googled and learned is a real place!—and his email is “pinchme@slickpoo.gov.” (I suppose it’s the “Pickle” and “poo” parts that will tickle young readers, but what really gets me, at age 37, is the “.gov.”)

I also would have felt, as someone who grew up with a disability, like this book was really trying to include kids like me. Newman ends her introduction by explicitly inviting readers with “different abilities—neurologically, cognitively, or physically” to contact her online with our advice about how to adapt and modify her advice to our abilities. In the illustration of How to Be a Gracious Host, the houseguest is a wheelchair user whose family picks him up in an adapted van.

Indeed, How to Be a Person could instead be titled How to Be Considerate and Helpful to All Kinds of People (and Animals and Plants) or How to Be a Good Citizen of the World. The part about How to Calculate the Tip says tipping is “not really optional, because folks in service jobs count on this money to make a living wage.” And the part about How to Contact Your Political Representatives features a drawing of a young person holding up a sign with the protest slogan “This Is What Democracy Looks Like.”

At least, it’s what it could look like, if we teach our children well.

Book illustrations: Debbie Fong; Newman: Mars Vilaubi