Here in L.A. we’ve been mostly spared the kind of experience they’re having in New York and some other cities. Patient volume at my hospital has actually gone down, because people who use the emergency department for semi-elective reasons have stayed away. It’s very different on the East Coast, where they’ve been so overwhelmed that ERs are filled with COVID patients who would normally be in an ICU.

I’m 61, with steroid-dependent asthma, and so have not worked clinically since mid-March. But if the volume of cases created a physician shortage here, I would feel compelled to serve. I’m still teaching medical students, conducting research, mentoring others in their research and working as an editor.

I think the lessons we’ll learn from this crisis are severalfold. One is that we have long underfunded public health in this country. We’re so focused on the care of the individual and on this or that miraculous, complex, life-saving surgery that we neglect the health of communities. Second, our for-profit health system has left our country with no reserve beds and a maldistribution of existing beds. Consequently, we do not have the capacity to handle a surge in cases, and we don’t have the infrastructure for contact tracing. We will need at least 100,000 new public health workers if we are going to track down active cases and their contacts and isolate them. Needless to say, we need sufficient testing capacity to detect all active cases.

When it comes to determining how many people have been infected, we don’t necessarily need to test massively; we need to test strategically. Several studies have estimated that between 3 percent and 20 percent of the population have antibodies, depending on the locale. Even though this number is 50-fold higher than the number of people with a positive COVID-19 RNA test—the test for active disease—it is nowhere near enough to create herd immunity.

Thinking statistically can be a big challenge for people. In Los Angeles, we are estimating that about eight people per thousand have tested positive. Eight per thousand, it sounds like nothing, right? But with 20 million people in the L.A. basin, when you start multiplying that out, and you look at the number of ICU and hospital beds, that tiny percentage can generate a whole lot of activity—activity we’re not prepared to handle.

The situation creates social-judgment problems. Prognostications can say, “If an extra 2,000 people die but the economy is better, is that a good thing or a bad thing?” I’m not in a position to make those kinds of decisions. But as a physician I’ll tell you this: being overwhelmed unnecessarily, watching people die

unnecessarily, having to make choices about who gets a ventilator, are horrible positions to be in. The people who were on the streets protesting stay-at-home orders, I’d like to hear how they feel after standing in a busy ER or ICU watching people die unnecessarily, or after COVID has seriously affected one of their loved ones. I suspect they will have a different attitude.

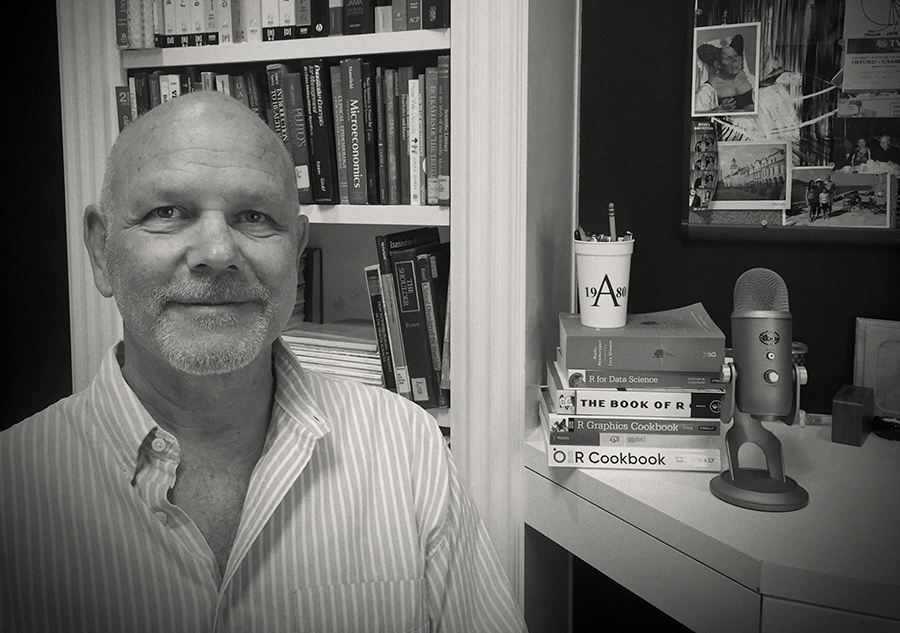

Dr. David Schriger ’80, professor and vice chair of emergency medicine at UCLA; associate editor of JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association