These nine essays include “On Golf,” about growing up in a golfing clan whose fairway styles reflect their roles in the family gestalt. “Guns in My Life” chronicles the ups and downs of an older brother, Jack, whose passion for guns and cars takes him to an unexpected life out West.

In “Looking Through the Knothole,” the adult Henry returns to Pennsylvania to visit his dying mother and delve into the difficult history of his father, an alcoholic who stumbled badly in midlife, causing what Henry calls “the near-destruction of our family,” only to pick himself up and find a sort of redemption.

“Long Distance” offers an account of another, long-envied older brother, Chuck, a successful surgeon whose life falls into disarray in middle age, and from whom Henry fields drunken, embittered phone calls. Surveying a broad reach of time, Endings & Beginnings poignantly connects childhood potentials with adult outcomes.

For Henry, these narratives are exercises in candor. “I am a tense, interior person,” he blurts confessionally to a massage therapist who’s working on him. Throughout his life, it seems, he has viewed himself as not the most talented person in the room—“never the equal of the gifted,” he writes in “On Swimming”— and a central task of this memoir is to take the measure of the modest success.

He does not flinch from exploring what he calls “my own shortcomings and despair,” reflected in a sense of insufficient accomplishment (his big novel and subsequent family biography, he reports, “were rejected repeatedly, until the agent gave up”). In a golf game with acclaimed novelist Tim O’Brien, Henry turns in an awful round, his sense of failure as a writer ramifying perilously.

Though the author turns 80 this year, many of these essays reflect the perspectives of 15 years ago or so, when he was in his 60s and deep in the toils of being an older dad, including coping with his adopted son, a teen prone to angry outbursts. “Father of the Bride” delivers a vicariously distressing account of the young adulthood of his daughter, who has an unplanned child with her irresponsible grifter of a boyfriend and suffers a psychotic break.

Despite its hard themes, Endings & Beginnings proceeds in a pleasurably happenstance manner, Henry’s prose conveying a diaristic and epistolary feel, full of attentive family updates. His preoccupation with time provokes the occasional swoon of memory, his visit home to Pennsylvania featuring an Updikean evocation of the names of bygone stores (Moffo’s Shoe Repair, Wack’s Druggists) and of his long-ago country club, where “I can visualize the golf course even now, hole by hole, a lifetime later.”

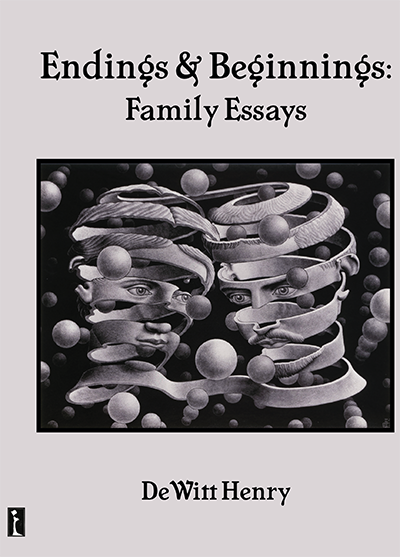

Endings & Beginnings: Family Essays

By DeWitt Henry ’63

MadHat Press

At this point in his journey, Henry inhabits a vantage point from which the coming-of-age story has long yielded to the “How’d I do?” story, and with admirable equanimity he assesses his life’s professional and artistic setbacks, family crises and, above all, “the losses and the toll of time.” Endings are sad, and the youngest sibling in a family eventually has a lot of them to confront. One brother dies of cancer in his mid-60s, the other of respiratory disease at 70. Henry travels to see his sister and finds her house crammed with art created by her late son, who died of AIDS.

Along with these endings, as his title promises, come new starts. After lengthy struggles, and to his delight, his daughter emerges into happiness—and like Shakespeare’s comedies, Henry’s account closes with nuptials, in the form of a waterfront wedding.

Throughout this lucid, attractive memoir, regret and joy hang in fine balance, and ultimately the author discovers in himself a perhaps-unexpected resilience. “What my mother called ‘the great adventure of life’ is fresh within me most mornings,” he writes. Can the near-octogenarian hope for more than that? Can anyone?

Cooper is a contributing editor at Commonweal.

Illustration by Adam McCauley