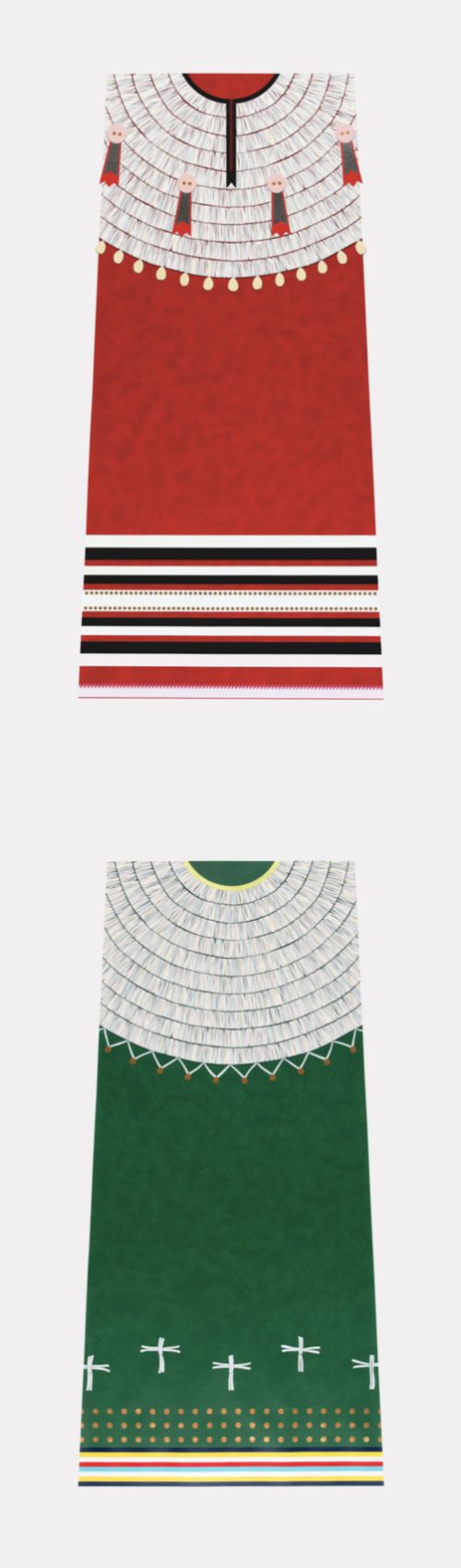

Top: Wačháŋtognaka/Nurture

Second: Nakíčižiŋ/Protect

2019

Screen prints with metal foil

55 ½ inches by 32 inches

Bottom: Dyani White Hawk

Among the Mead Art Museum’s recent acquisitions are Wačháŋtognaka/Nurture and Nakíčižiŋ/Protect, two screen prints of Lakota dentalium dresses from the four-print series Takes Care of Them, by Dyani White Hawk, a Sičáŋgu Lakota artist. In 2020, when the Smithsonian Institution organized the first national exhibition on the artistic achievements of Indigenous women, it noted that “women have long been the creative force behind Native American art, yet their individual contributions have been largely unrecognized, instead treated as anonymous representations of entire cultures.” That same year, the Mead purchased Nurture and Protect through the Trinkett Clark Memorial Student Acquisition Fund, which allows students to act as curators, selecting works for the permanent collection.

Takes Care of Them speaks to the ways that the women in our communities and our feminine relatives collectively care for our communities at large. It’s not just Mom, it’s not just Grandma. It’s the combination of mother, grandma, aunty, cousin, sister. The titles speak to four of the ways that our women collectively care for us: the way that they lead, create, protect and nurture us.

Nakíčižiŋ does not directly mean “protect”; it’s more “to defend,” or “to be in the defense of someone or something.” The dragonfly symbol on the dress is a representation of that concept. Dragonflies in our communities are looked at as some of the first warriors or protectors. Wačháŋtognaka does not mean “nurture.” I was in conversation with an aunty of mine, looking through the dictionary: wačháŋtognaka does not directly translate. The word speaks to generosity, sympathy, compassion, affection at large, which are concepts that I relate to the word “nurture.”

I hope folks will think about the contributions of Native art to the artistic history of this landbase, and the importance and relevance of that. Native art and aesthetics have influenced the development of art on this continent, but Native art is not taught, centralized or prioritized in mainstream academia in the way that I feel it should be. So, a lot of the works that I create, I create them large. Not all of them, but a lot of them, with the intentionality of making sure that they are seen, that they are honored and recognized in our artistic spaces as having equal value to anything else in that space and any other person or artistic contribution within those spaces. These two pieces are representations of the artistic history of this land.

Photo courtesy Dyani White Hawk