Like a kitchen cook dicing carrots while chatting on the phone, the food memoirist is a deft multitasker, delving into this or that dish even while reporting a romance, recalling a childhood hurt or exploring a far-flung culture. Such masters of the American-in-Paris foodie chronicle as M.F.K. Fisher, A.J. Liebling and the Ernest Hemingway of A Movable Feast fuse the culinary and metaphorical properties of appetite in a seamless merging of the meals eaten and the life lived.

Alexander Lobrano ’77’s account of three decades spent as a food writer in the City of Light charts a career cooked up out of seemingly meager ingredients. That career begins haphazardly when, having stumbled in his late 20s into a job as a Europe-based menswear magazine editor, Lobrano realizes that his true passion isn’t for what people wear, but for what they eat. A lateral move in lifestyle journalism soon follows.

A would-be Parisian food critic at age 30, Lobrano is a raw innocent. He doesn’t know herbs or cheeses or oysters. He has never eaten foie gras. At a bistro with friends of friends, he doesn’t know that the woman he’s talking with is Julia Child. Served grilled thrush at a dinner party, he recoils at the taste (“wet dog”) and ferrets the tiny drumstick into his blazer pocket—then, when he gets back to his flat, orders a pizza. Beset by surging feelings of fraudulence, he is daunted by “the immensity of everything I didn’t know about France’s language and food.” Conducting an interview with a master fromager, he nods knowingly at a torrent of expertise while scribbling “Oh God! Help!” in his notebook.

He proves tenacious and finds assorted helpmates to play Higgins to his Eliza. His obliging landlady, a countess, untangles the intricacies of French table manners (eat asparagus with your fingers, not knife and fork) and counsels him to “decipher a cook’s intentions.”

The novice critic certainly doesn’t lack for chutzpah. When he writes a snarky takedown of the famed brasserie La Coupole, the enraged owner calls him in and subjects him to a taste test to identify which bearnaise sauce is fresh-made and which from a mix (Lobrano gets it right). His brash reviews attract attention, and eventually, he becomes Gourmet magazine’s Paris correspondent. Soon Lobrano is touring food markets with chef Paul Bocuse and flying to Barcelona to interview El Bulli’s Ferran Adrià. These sections of his book deliver an entertaining account of the toils and thrills of a high-level food and travel journalist.

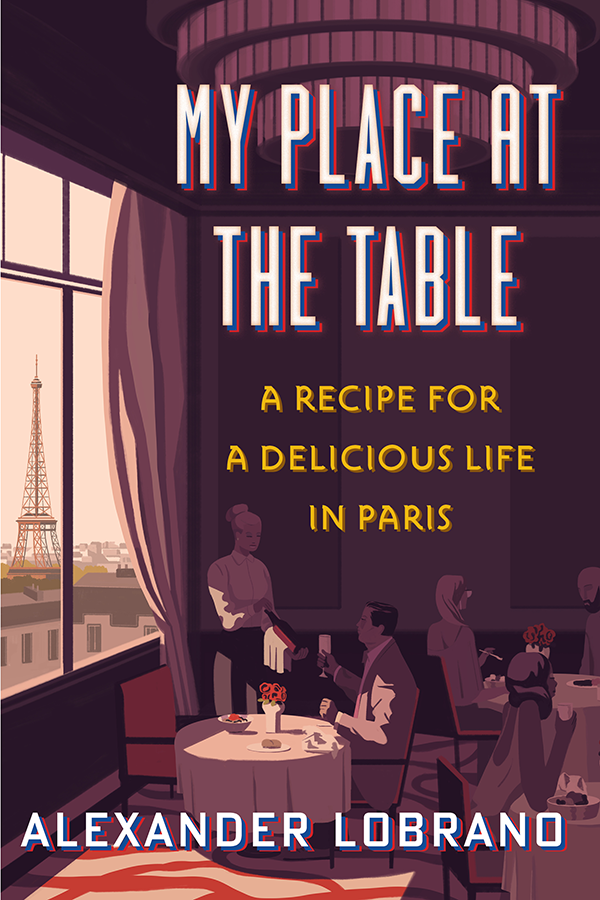

By Alexander Lobrano ’77

HarperCollins

My Place at the Table is also a culinary bildungsroman, taking us on excursions into Lobrano’s early-1960s suburban Connecticut boyhood. His arty proclivities irk his businessman father, who dismisses his interest in flowers as “girly” and cruelly calls a charming second-grade essay on his favorite sandwich, the BLT, “a dumbbell paper,” exhorting him to write about sports instead. Anxious and dreamy, “a bookish introvert” lost amid “gangs of grinning boys,” the young Lobrano is painfully out of compliance with prevailing codes of American maleness of the era. His title echoes the 1993 book by gay writer Bruce Bawer, A Place at the Table, and his own memoir focuses the fervent hope for a life that will allow for loving flowers, food and other men.

Lobrano’s epigraph comes from novelist Jeanette Winterson—“What we notice in stories is the nearness of the wound to the gift”—and his elliptical references to “something bad that happened to me” hint at wounds of his own. But Lobrano keeps those wounds veiled. At times I felt another memoir hiding—one far more attuned to pain. Fisher’s and Hemingway’s evocations of Paris brim with the sense of time’s passage; descriptions of meals evoke the ravenous youthful hunger for love and for experience, triggering a rapturous nostalgia. The adverse memories at the core of Lobrano’s narrative—those wounds he hints at—make for a harder fit with the romance of a delicious life in Paris.

And would it be churlish to wish for a bit more spice in Lobrano’s sentences? Evoking a meal enjoyed at one of Alain Ducasse’s restaurants, he recalls, “The acidulousness of the cream pampered the firm, sweet flesh of the crustaceans, and the caviar was the fuse that lit the potent sensuality of this seemingly innocent composition.” As Lobrano himself muses, “gastronomic expertise per se is dull and can be irritating.” C’est vrai!

If the prose served up in My Place at the Table lacks Fisher’s elegant, incisive, slightly eccentric swooniness, or Hemingway’s time-struck and ardent sadness, well, the bar set by such writers is extraordinarily high. In chronicling an aspirational life brought to pass through pluck and luck, Lobrano writes with engaging humor and candor about his own youthful cluelessness, and just how he went about reversing it. “I’d like to write more about food,” he tells Julia Child when he finally figures out who she is. And what exactly does he have to say about food? she asks. “Not much yet,” he says, “but I hope to learn.”

Cooper, a longtime writer for Bon Appétit, currently reviews restaurants for The Hartford Courant.

Photograph by Steven Rothfeld