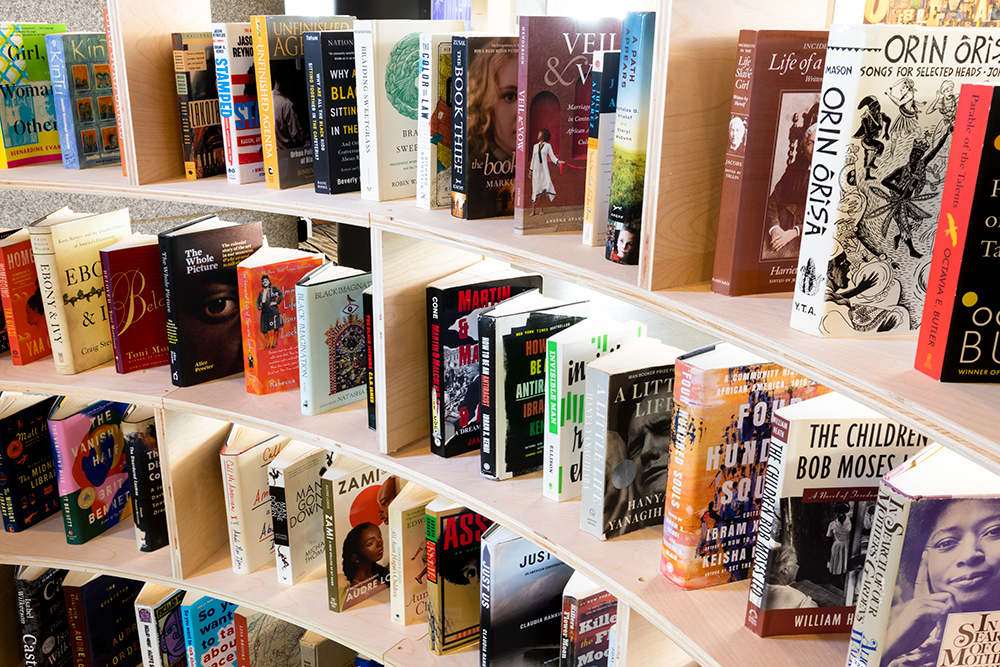

Clark—Amherst’s Winifred L. Arms Professor in the Arts and Humanities and professor of art and the history of art—herself sculpted many books, including the 2019 Bancroft Prize–winning

Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War, by Lisa Brooks, the Henry S. Poler ’59 Presidential Teaching Professor of English and American Studies. Brooks’ heritage is Abenaki and Polish, and her book, she says, “reframes the historical landscape of ‘the first Indian War,’ more widely known as King Philip’s War (1675–78).”

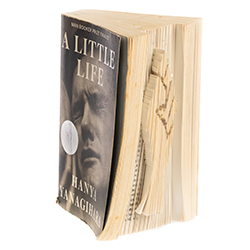

Amir Hall ’17 sculpted

A Little Life, by Hanya Yanagihara. “Perhaps my favorite moment is when Willem notices Jude’s lacings are untied before Jude does, and bends to tie them, because Jude, whose mobility is limited by a severe spinal injury, isn’t able to do so himself,” Hall says. “It was amazing to see men capable of caring for each other outside of romantic relationships.” For Hall, that moment “feels like what solidarity is—this all-encompassing awareness of and care for another’s safety and ability; a filling of another’s gaps.”

Tyra Redwood ’25 chose to sculpt Mark Oshiro’s 2018 YA debut novel,

Anger Is a Gift, set in Oakland, Calif. It’s about a Black teen and his friends—other teens of color, diverse in gender and sexuality—who work together to protest acts of systemic violence in their community. As one character’s mother says, invoking the novel’s title, “Anger is a gift. Remember that. You gotta grasp on to it, hold it tight and use it as ammunition. You use that anger to get things done instead of just stewing in it.”

Some of the solidarity fists were fabricated in group settings on campus, while others were made solo. The idea was to pick a book that honored an idea of solidarity. “When our work comes together, our voices come together,” Clark says. “What does it mean to have a multivocal solidarity? What does it mean to have everybody’s book? They all have fists, but each is by a different hand who made it. There’s power in that, too.”

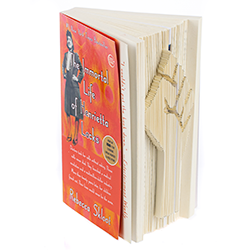

Claire Macero ’25 sculpted

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, by Rebecca Skloot. It tells the true story of the Black woman whose “HeLa” cells lived on after her death from cancer, and were pivotal in creating scientific breakthroughs from the polio vaccine to gene mapping to in vitro fertilization and more. It’s also a story of exploitation and marginalization: the Lacks family reaped none of the profits that science gained.

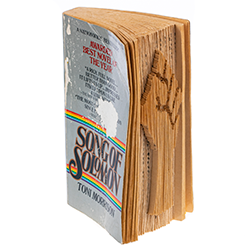

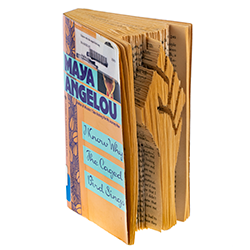

“I chose

Song of Solomon, by Toni Morrison, because of the way it made me think more critically about the intersection between socioeconomic freedom and race in the United States,” writes

Luke Munch ’25. “

Song of Solomon helped illuminate how others outside of my perspective struggle.”

Every time someone submitted a personal reflection or sculpted a book, the College pledged funds, and now $100,000 has been committed to organizations that support Black and Indigenous communities. Recipients include national organizations such as the United Negro College Fund and regional ones like the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project. “As we are making and reflecting,” Clark says, “we are also giving.”

Emily Potter-Ndiaye, a Mead Art Museum curator, first read Angela Davis’ 1981 book

Women, Race and Class when she was 19, in an intro class in women’s and gender studies. “It taught me how women with privilege contribute to other women’s oppression, and how Black women’s political imaginations for liberation have shaped progress in the U.S. for generations,” she says. “Reading it at that moment ignited in me a seeking of other ways of being a white woman in the world—toward solidarity and mutual liberation.”

Provost and Dean of the Faculty Catherine Epstein sculpted Khalil Gibran Muhammad’s

The Condemnation of Blackness. Reading it, she saw the name Richmond Mayo-Smith, class of 1875, for whom an Amherst dorm is named. “While a pioneer in the field of statistics,” Epstein says of Mayo-Smith, “by today’s standard his work was profoundly racist and anti-immigrant.” For Epstein, Muhammed’s book “is a stark reminder of the College’s racist past” and the work that remains “to uncover challenging aspects” of our history.

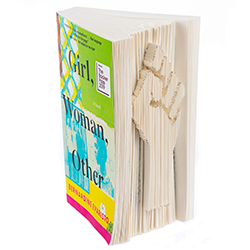

“White people are only required to represent themselves, not an entire race,” writes Bernardine Evaristo, whose eighth book, the novel

Girl, Woman, Other, won the 2019 Booker Prize and was sculpted by

Rachel Hendrickson ’25.