By Katherine Duke ’05

Oh, wow! There’s a woman. What’s she riding? She’s riding a sea monster!

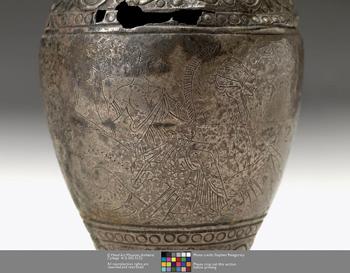

These were Pamela Russell’s thoughts one summer day in 2010 when she examined the scene intricately chased (indented with a fine tool) onto the silver perfume vessel she’d found in storage at the Mead Art Museum. This vessel—4 and a half inches tall and called an amphoriskos (“little amphora”)—at first appeared dulled and plain, but when she looked closely, she recognized a scene known as “The Arming of Achilles,” in which two sea nymphs called Nereids ride on a dolphin and a hippocamp (a hybrid horse-fish sea creature), bringing weapons and a helmet to the Trojan War hero.

“I was kind of shaking—I couldn’t believe what I was seeing,” says Russell, the Mead’s head of education and Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Academic Programs and a scholar of Greek and Roman art. “The quality of the drawing is really exquisite.” If it turned out to be authentic, she thought, it could be considered “among the finest pieces of silver known from ancient Greece.”

Classical silver vessels with chased figural decoration are “exceedingly rare, with perhaps no more than 25 examples known” worldwide, Russell explains, and nearly all of those are drinking vessels.

The artifact had been donated to the Mead in 1958 by New York philanthropist Susan Dwight Bliss. The Mead’s first director, Charles Morgan, identified and dated it fairly accurately in the catalogue cards: silver vessel, Greek, fourth century B.C.E. But Russell was puzzled to see no mention of it in Frank Trapp’s 1979 guide, The Classical Collection at Amherst College.

She and current Mead Director Elizabeth Barker had the vessel’s condition briefly assessed by Boston conservator Nina Vinogradskaya, who called it a “complicated and intriguing object.” Russell presented a paper on it to the Archaeological Institute of America in January 2012.

This past spring, art conservation scientist John Twilley at Stony Brook University subjected it to many weeks of analysis. He determined that, though its body was most likely authentically ancient Greek, its handles were a recent addition, probably soldered on in the late 19th century.

When her research took her to Harvard this summer, Russell found documents showing that Susan Bliss’ mother, Jeanette, had purchased the vessel at a 1908 New York City auction. She’d bought it for $180 from Edward Colonna, a celebrated Art Nouveau designer who might well have added the handles himself.

The Mead is planning an exhibition next year in celebration of the vessel. Russell believes the vessel’s story “encapsulates what we try to do at the Mead, which is encourage close looking and multidisciplinary inquiry.”

And there is much more inquiry to be done, largely because the Mead’s perfume holder, it seems, is unique. Russell imagines that could be why Morgan relegated it to storage and Trapp excluded it from his book—they simply didn’t know what to make of it.

“Being one-of-a-kind is a blessing and a curse, because it’s, of course, rare and exciting and terribly important,” she says. “But without brothers and sisters—without things to compare it directly to—we’re left with more questions.” For instance: Were there other handles on the vessel when it was originally crafted, before the addition of the new ones? And where exactly, in or around Greece, was it unearthed?

This treasure, she says, is “not revealing its secrets easily. It’s taking time.”

Photo by Stephen Petegorsky