Photographs by Tsar Fedorsky

Fedorsky is an editorial photographer specializing in portraiture. Her work has appeared in many national publications.

Living in the Boston area, with its high concentration of colleges and universities, I was struck by the many academics featured in the local press. These articles often included references to former teachers. It seemed to me that an academic’s greatest accomplishment might well be the influence he or she had on exceptional students, and so I decided to photograph mentors and their protégés.

As I started work on the project more than 10 years ago, I asked each subject to write a personal statement about his or her mentor. Since then, the project has evolved geographically and now includes a diverse group of professionals from various fields—including the Amherst alumni pictured on these pages, most of whom are from my era at the college.

In addition to meeting such interesting people, one of the most exciting parts of the project has been reading the personal statements. Often, the stories reveal that mentors are not special because of any one grand action they’ve taken. They’re special simply because they took the time to share their wisdom and to be present in other people’s lives. These “teachers” inspired confidence and faith in their protégés at pivotal moments.

When I began the project, I wasn’t aware that I had a mentor. Now I know that two people have played that role in my life. One is William Broder, an author (and the father of an Amherst classmate!). The other is Israel Horovitz, a playwright. I could always count on them to offer advice and support with artistic decisions, frustrations and (occasionally) joys.

See the photos and statements of...

Dan Duquette ’80

Executive vice president of baseball operations for the Baltimore Orioles and former Boston Red Sox GM

To Harry Dalton (at right in photo):

“When someone believes in you, it helps to keep the Green Monster at bay.”

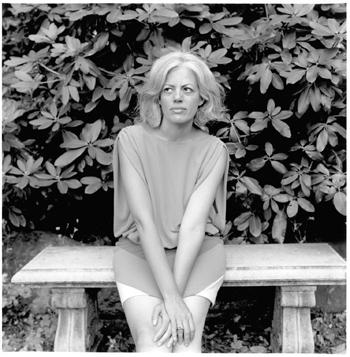

Yanira Castro ’94E

Brooklyn, N.Y.-based choreographer

I feel like I have an army of female mentors. I come from a family of strong women, insane in their work ethic and seemingly boundless in their energy. I owe a lot to mythical stories of their mischief and brazenness.

But in the more direct meaning of mentor—a teacher—I think of two women especially: my Amherst theater and dance professors Wendy Woodson and Suzanne Palmer Dougan.

When I think of Wendy, I think of a long list of words divided by slashes that never quite define what you are doing—that can’t circumscribe the action—but that, by existing side by side, create other contexts. I think of multiplicity, and I think of structures. I think of having to keep choreography straight as 1A, 2B and 3D and then, in a split second, having to remember and do 3D, 1Bx2 and 2A. It was the first language I deeply understood.

When I think of Suzanne, I think of Euripides’ Trojan Women. And I think about seeing. I remember distinctly drawing lines of objects: hundreds of chattering teeth in straight lines and a ceiling of hanging meat in grids. I thought that everyone saw the world that way: in numbers and in repetition. She taught me that it was a distinct way of seeing and to cultivate it. It was the first time I understood that refined perception was crucial.

These women sent me into the world with confidence that I have, at times, lost and have had to fight to regain/resurface/rediscover (there is Wendy). But I am doing what I am doing entirely because they stepped in and taught me that I had a language to hone.

That kind of trust in your vision is a gift. Staying true is the singular and nearly impossible task

Chris Bohjalian ’82

Best-selling author

I see Howard Frank Mosher no more than once every two years. We both live in Vermont, and Vermont is indeed a small world, but the Green Mountains rise like a great animal’s spine across the vertical center of the state, and it takes a full afternoon to get from his corner to mine. Still, we do speak with some frequency, and I recognize instantly his good-natured whoop of a laugh on the phone.

I’ve looked up to Howard as a mentor for a decade and a half—since I was a very young writer with only one mesmerizingly bad novel to my credit. The first of his novels that I read was his tale of fathers and sons and racism in Vermont, A Stranger in the Kingdom. I am not a weepy guy, but I remember sitting alone on the front steps of my home on a Saturday morning when I finished it, and discovering (much to my astonishment) that my eyes had grown moist. Immediately I embarked upon the rest of the Mosher canon, stories set in Vermont’s frontierlike Northeast Kingdom, about bootleggers, loggers and women and men of truly indefatigable optimism—and I savored it all.

Yet I don’t view Howard as a mentor simply because he is an immensely gifted storyteller (though he is). I know a great many talented writers.

What makes Howard special in my mind, and the reason that I dedicated my novel Water Witches to him, is his absolute unwillingness to endure the affectations and rivalries that pepper the literary life. He wants to write, not talk about writing, and his work ethic is unassailable. I’ve always presumed this was why he lasted about a week in San Francisco when he was a fledgling novelist, and why he lives now in a northern village where the cross-country skiing is exceptional even in April and he need never fear being cornered at a literary cocktail party. Certainly Howard enjoys meeting his readers in bookstores and diners and when he runs into them while fishing, but I don’t believe he has ever in his life given a formal reading from his work. He is a remarkable raconteur, but—by design—the stories will never include names you’ve ever heard of. He hasn’t a curmudgeonly or cantankerous bone in his body, unless you are a book reviewer who has criticized harshly the work of one of his friends.

He is, perhaps, loyal to a fault. He has probably defended books that I would consider indefensible from a literary perspective. But my sense is that this is less because Howard is oblivious to a book’s flaws than because he will work so hard to find (and celebrate) a book’s merits.

This is very much the way Howard approaches people, too: He may see their shortcomings. But, invariably, he will focus instead on their strengths.

Sung-Joo Kim ’81, ’00 Hon

Chairwoman and CEO of Sungjoo Group and MCM Holdings

My father was one of the biggest tycoons in Korea. My mother, while brought up very traditionally, was also a very strict Christian. Instead of pursuing a life of luxury, she devoted her wealth and time to helping others in the Korean community as well as around the world. I was brought up in the combination of Confucian tradition from my father and Calvinistic Christianity from my mother.

I was of a new generation that also included those raised with some Western influence. While I was amazed by my mother’s dedication to others, I knew that I did not want to marry another wealthy Korean or have a big family. I decided to pursue a college degree abroad, a goal that did not meet with my father’s approval. Until I arrived at Amherst in 1979, I had never studied English.

After Amherst, I attended Harvard Divinity School, combining economics and business ethics as a joint program. I rebelled against the traditional match-making marriage from Korea and married a non-Korean (British-Canadian) who came from a humble background. I was completely expelled by my family. But I knew that if I did not break with my family, I could be just another wealthy woman who married another billionaire, and that was not what I wanted to do.

My brothers inherited multi-billion-dollar companies, but I inherited intelligence and ambition from my father. (As a daughter, I was not included in the inheritance.) I launched my own business from scratch and built it into a successful international corporation.

With my strong Christian background, my motto became “succeed to serve,” something my mother had done in her philanthropy work and which I have incorporated into my business model. It includes the following three missions: The first is to prove that a Korean woman can succeed in business, to encourage and empower other women. The second is to stand up to corruption by being smarter and working harder. The third is to prove that small-to-medium companies, with hard work and smart strategies and execution, can compete with giant companies on a domestic and global scale.

Strangely enough, it was my mother’s example as a Christian that has guided me all along and that has proved to be the life force of the business. I founded a nonprofit foundation to support global charity projects and have donated 10 percent from net profit of Sungjoo Group and more than 20 percent of my personal income annually. When North Korea opens up, I hope to use my resources to help and mentor women and children in North Korea.

My mother’s dedication to making positive changes in other people’s lives has worked as a strategy for me throughout my personal and business life. Succeed to serve.

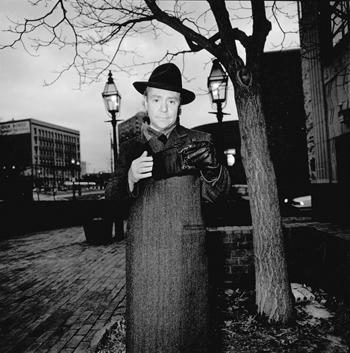

Teller ’69

Illusionist and entertainer

My mentor, David G. Rosenbaum, was an English teacher and a drama coach at Central High School in Philadelphia. He also moonlighted as a magician, performing in the character of the Devil posing as a Scottish party conjurer.

Fond of black hats and scarlet waistcoats, he used to say, “There’s no such thing as being overdressed.”

“Rosey”—as we students nicknamed him—stayed late after school making kids into actors. He taught technique (e.g., how to doff an overcoat without distracting from the dialogue), but, more importantly, he taught method (e.g., see the mental pictures before you say them in the words of the lines).

He and I stayed friends for over 30 years, until his death, and he lives in everything I do. Watch me take off an overcoat while I talk. You won’t miss a word.

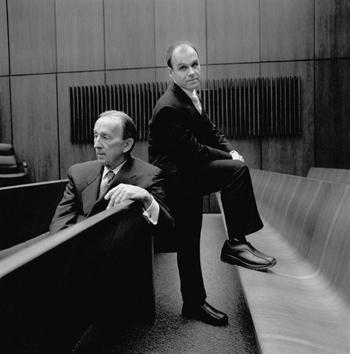

Scott Turow ’70

Attorney and best-selling author

Thomas P. Sullivan (at left in photo) became the U.S. attorney in Chicago in July 1977. I had just finished my second year in law school and was working in that office for the summer, with hopes of being hired as an assistant U.S. attorney after I graduated. I was terrified when I (along with another intern) was assigned to do a research project for the new federal prosecutor on one of his first days in office. In truth, everyone in the office was scared of Tom Sullivan. A career defense lawyer, Tom came to the job vowing to curb the excesses of an office with which he’d often done battle. The other intern and I were supposed to survey the case law and compile a memo illustrating the kinds of remarks the courts had criticized local prosecutors for making in closing argument. The young AUSAs, Tom said when I met with him, all suffered from the same fundamental misperception.

“Facts win cases,” Tom told me. “Not lawyers.”

I count that as the first of countless lessons Tom Sullivan has taught me over the past quarter century. It was nearly the last, however, because Tom was reluctant about hiring me permanently. Right after that initial summer had ended, I published my first book, One L, a memoir of law school. It was a considerable success, but Tom required extensive reassurance that I didn’t want to become an AUSA in order to write about the experience. Even at that, Tom seemed to hire me against his better judgment.

After I had been on the job a little more than a year, I found myself working at Tom’s side again, as the junior prosecutor on the income tax fraud trial of William J. Scott. Scott, at the time, was Illinois’ most popular politician, the state’s sitting attorney general who had won re-election with 84 percent of the vote. As his indictment drew near, Scott vowed to destroy Tom Sullivan. The prestige and credibility of the office and perhaps Tom’s career were on the line, and the 11-week trial was a grueling 18-hours-a-day, seven-days-a-week enterprise.

My initial role was to do legal research and write memoranda. Tom would make me sit beside him while he edited my drafts with a Ticonderoga number two pencil. It was not entertaining watching my work torn apart, but Tom explained every change.

Eventually, I was trusted with a role in court. Tom’s house was near mine, and we often traveled back and forth together, talking about the case, with Tom teaching me by example and anecdote about strategy, cross-examination and the entire art of being a trial lawyer. Tom was a frank critic. But that meant you had no need to doubt the sincerity of his praise. I still count it as one of the greatest honors of my lawyering life when Tom decided that I, 18 months out of law school, would deliver the initial portion of the summation for the government in what Tom openly regarded as the most important case of his career. We won.

Within a year, I was working by Tom’s side again as we wrote our response to Scott’s appeal, which Tom allowed me to argue before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit.

I learned two things from Tom Sullivan. The first was how to practice law. He remains on the select list of the best lawyers I know. More than anything else, he showed me how to be demanding of myself. Ten years after that first summer, at the same time I went into private practice, Tom ended up demonstrating for me how to deal with a client, because he successfully represented me in a painful dispute I’d gotten into with the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals. The other thing I learned from Tom was how the public’s business should be done. Tom Sullivan is the finest public servant I have ever seen up close. He has wanted nothing for himself from any of his public jobs, except to maintain his reputation for integrity. He has never learned to coast.

The day Tom hired me as an assistant U.S. attorney, he showed me the code of federal regulations, to reinforce the fact that I couldn’t write about the job he was reluctantly giving me.

“And besides that,” he added, getting to what I suspected was the real point, “don’t you ever write about me.”

For 25 years, I’ve kept that promise. Until now.

Adrienne E. White-Faines ’82

Vice president and chief health officer, American Cancer Society of Illinois

Many mentors have helped to inspire, shape, mold and influence me as a woman of color, a mother and a professional. But the foundation of guidance for my existence continues to stem from my family, especially from my parents and grandparents. It is my mother and father from whom my values, faith and focus evolved, shaping my personal choices, professional behavior and world perspective. Winifred Parker White and Walter Hiawatha White passed along the stories of family strength and resilience from my African American and Cherokee heritage, providing clarity on who I am and “whose I am.”

All others mentors were then tested and measured against my parents’ teachings. And I have been blessed to know and claim other mentors who demonstrated values similar to those of my parents. As I grew up in the ’60s and ’70s, my professional mentors were predominately men, who, in their positions, exhibited humility, honesty, a devout sense of values and authentic respect for faith. These health executives, faith-based leaders, clinicians and community leaders earned my respect as mentors because they affirmed these lessons that my parents taught, valued and displayed consistently throughout their lives:

“Faith” is knowing that it’s not all in your control.

There is nothing you can’t learn (as opposed to, There is nothing you can’t do!).

Don’t run from adversity; learn from it.

You can’t get anywhere alone, and if you did, what’s the fun in that?

Embrace the fact that, for every door that opens for you, you have an obligation to help another come through behind you.

Always do what’s right (not what is expedient or comfortable).