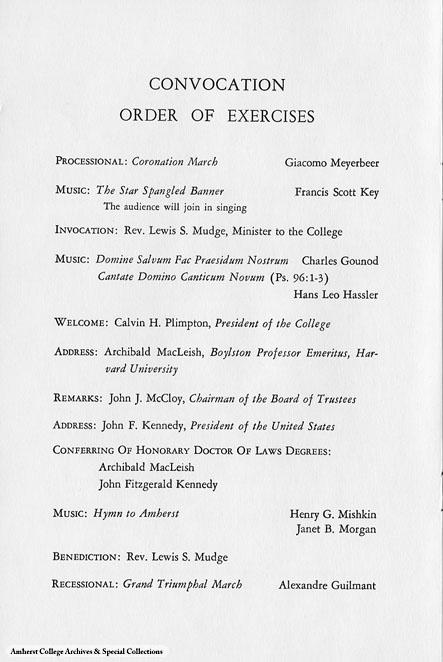

3. Planning Documents:

4. Text of President Kennedy's Convocation Address:

Reproduced courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Library, President’s Office Files, Speech Files, Box 47.

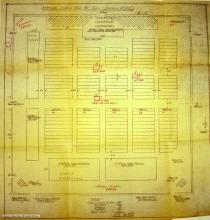

THE PRESIDENT'S CONVOCATION ADDRESSMR. McCLOY, President Plimpton, Mr. MacLeish, distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen:I am very honored to be here with you on this occasion which means so much to this College and also means so much to art and the progress of the United States.This College is part of the United States. It belongs to it. So did Mr. Frost, in a large sense, and, therefore, I was privileged to accept the invitation somewhat rendered to me in the same way that Franklin Roosevelt rendered his invitation to Mr. MacLeish, the invitation which I received from Mr. McCloy.The powers of the Presidency are often described. Its limitations should occasionally be remembered, and, therefore, when the Chairman of our Disarmament Advisory Committee -- who has labored so long and hard, Governor Stevenson's assistant during the very difficult days at the United Nations, during the Cuban crisis, a public servant of so many years - asks or invites the President of the United States, there is only one response. So I am glad to be here.Amherst has had many soldiers of the King since its first one, and some of them are here today: Mr. McCloy, who has been a long public servant; Jim [James A.] Reed, who is the Assistant Secretary of the Treasury; President [Charles W.] Cole, who is now our Ambassador to Chile; Mr. [James T.] Ramey, who is a Commissioner of the Atomic Energy Commission; Dick [Richard W.] Reuter, who is head of the Food for Peace. These and scores of others down through the years have recognized the obligations of the advantages which the graduation from a college such as this places upon them: to serve not only their private interest but the public interest as well.Many years ago, Woodrow Wilson said, "What good is a political party unless it's serving a great national purpose?" And what good is a private college or university unless it's serving a great national purpose? The library being constructed today - this College itself, all of this, of course, was not done merely to give this school's graduates an advantage, an economic advantage, in the life struggle. It does do that. But in return for that, in return for the great opportunity which society gives the graduates of this and related schools, it seems to me incumbent upon this and other schools' graduates to recognize their responsibility to the public interest.Privilege is here, and with privilege goes responsibility. And I think, as your President said, that it must be a source of satisfaction to you that this school's graduates have recognized it. And I hope that the students who are here now will also recognize it in the future.Although Amherst has been in the forefront of extending aid to needy and talented students, private colleges, taken as a whole, draw 50 per cent of their students from the wealthiest 10 percent of our nation. And even state universities and other public institutions derive 25 percent of their students from this group. In March 1962, persons of 18 years or older who had not completed high school made up 46 percent of the total labor force, and such persons comprised 64 percent of those who were unemployed. And in 1958, the lowest fifth of the families in the United States had 4 1/2 percent of the total personal income, the highest fifth 45 1/2 percent.There is inherited wealth in this country and also inherited poverty. And unless the graduates of this College and other colleges like it who are given a running start in life -- unless they are willing to put back into our society those talents, the broad sympathy, the understanding, the compassion -- unless they're willing to put those qualities back into the service of the Great Republic, then obviously the presuppositions upon which our democracy are based are bound to be fallible.The problems which this country now faces are staggering, both at home and abroad. We need the service, in the great sense, of every educated man or woman, to find 10 million jobs in the next 21/2 years, to govern our relations -- a country which lived in isolation for 150 years, and is now suddenly the leader of the Free World -- to govern our relations with over 100 countries, to govern those relations with success so that the balance of power remains strong on the side of freedom, to make it possible for Americans of all different races and creeds to live together in harmony, to make it possible for a world to exist in diversity and freedom. All this requires the best of all of us.And therefore, I am proud to come to this College whose graduates have recognized this obligation and to say to those who are now

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I -

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

I hope that road will not be the less traveled by, and I hope your commitment to the great public interest in the years to come will be worthy of your long inheritance since your beginning.This day devoted to the memory of Robert Frost offers an opportunity for reflection which is prized by politicians as well as by others, and even by poets, for Robert Frost was one of the granite figures of our time in America. He was supremely two things: an artist and an American. A nation reveals itself not only by the men it produces but also by the men it honors, the men it remembers.In America, our heroes have customarily run to men of large accomplishments. But today this College and country honors a man whose contribution was not to our size but to our spirit, not to our political beliefs but to our insight, not to our self-esteem, but to our self-comprehension. In honoring Robert Frost, we therefore can pay honor to the deepest sources of our national strength. That strength takes many forms, and the most obvious forms are not always the most significant. The men who create power make an indispensable contribution to the nation's greatness, but the men who question power make a contribution just as indispensable, especially when that questioning is disinterested, for they determine whether we use power or power uses us.Our national strength matters, but the spirit which informs and controls our strength matters just as much. This was the special significance of Robert Frost. He brought an unsparing instinct for reality to bear on the platitudes and pieties of society. His sense of the human tragedy fortified him against self-deception and easy consolation. "I have been," he wrote, "one acquainted with the night." And because he knew the midnight as well as the high noon, because he understood the ordeal as well as the triumph of the human spirit, he gave his age strength with which to overcome despair. At bottom, he held a deep faith in the spirit of man, and it's hardly an accident that Robert Frost coupled poetry and power, for he saw poetry as the means of saving power from itself. When power leads man towards arrogance, poetry reminds him of his limitations. When power narrows the areas of man's concern, poetry reminds him of the richness and diversity of his existence. When power corrupts, poetry cleanses. For art establishes the basic human truths which must serve as the touchstone of our judgment.The artist, however faithful to his personal vision of reality, becomes the last champion of the individual mind and sensibility against an intrusive society and an officious state. The great artist is thus a solitary figure. He has, as Frost said, a lover's quarrel with the world. In pursuing his perceptions of reality, he must often sail against the currents of his time. This is not a popular role. If Robert Frost was much honored during his lifetime, it was because a good many preferred to ignore his darker truths. Yet in retrospect, we see how the artist's fidelity has strengthened the fiber of our national life.If sometimes our great artists have been the most critical of our society, it is because their sensitivity and their concern for justice which must motivate any true artist, makes him aware that our nation falls short of its highest potential. I see little of more importance to the future of our country and our civilization than full recognition of the place of the artist.If art is to nourish the roots of our culture, society must set the artist free to follow his vision wherever it takes him. We must never forget that art is not a form of propaganda; it is a form of truth. And as Mr. MacLeish once remarked of poets: "There is nothing worse for our trade than to be in style." In free society art is not a weapon and it does not belong to the sphere of polemics and ideology. Artists are not engineers of the soul. It may be different elsewhere. But democratic society-in it-the highest duty of the writer, the composer, the artist is to remain true to himself and to let the chips fall where they may. In serving his vision of the truth, the artist best serves his nation. And the nation which disdains the mission of art invites the fate of Robert Frost's hired man, the fate of having nothing to look backward to with pride and nothing to look forward to with hope.I look forward to a great future for America - a future in which our country will match its military strength with our moral restraint, its wealth with our wisdom, its power with our purpose. I look forward to an America which will not be afraid of grace and beauty, which will protect the beauty of our natural environment, which will preserve the great old American houses and squares and parks of our national past, and which will build handsome and balanced cities for our future.I look forward to an America which will reward achievement in the arts as we reward achievement in business or statecraft. I look forward to an America which will steadily raise the standards of artistic accomplishment and which will steadily enlarge cultural opportunities for all of our citizens. And I look forward to an America which commands respect throughout the world not only for its strength but for its civilization as well. And I look forward to a world which will be safe not only for democracy and diversity but also for personal distinction. Robert Frost was often skeptical about projects for human improvement, yet I do not think he would disdain this hope. As he wrote during the uncertain days of the Second War:

Take human nature altogether since time began,

And it must be a little more in favor of man,

Say a fraction of one per cent at the very least,

Our hold on the planet wouldn't have so increased.

Because of Mr. Frost's life and work, because of the life and work of this College, our hold on this planet has increased.

ARCHIBALD MACLEISH'S CONVOCATION ADDRESS

Reproduced from the Amherst Alumni Quarterly, Fall 1963

FROST AND STONEMY PRESENCE here today is proof - if any is needed in a college as civilized as Amherst - that you can't learn by experience. By which I mean that this is not the first time I have assisted a President of the United States to start a library. It was some twenty odd years ago at Hyde Park in the State of New York where a building had been constructed to house the papers of Franklin Delano Roosevelt - which was all very well except for two facts: that I was Librarian of Congress at the time, having just been appointed to that office by Mr. Roosevelt, and that the Library of Congress, down at least to the date of my appointment, had itself been the usual repository for Presidential papers.Mr. Roosevelt's invitation to me to speak at Hyde Park - if "invitation" is the world I want - was, I dare say, kindly meant: there was to be nothing personal about the affront. But it is one thing for an invitation to be kindly meant and another thing altogether to accept it in kind - particularly when it involves a speech by the director of the library to which invaluable papers ought to have gone, celebrating the opening of the library to which they are going. I made, I am told, a memorable impression. Indeed, my friend and classmate, Dean Acheson, on whose unfailing candor I have always been able to rely whether I wanted to or not, assured me on my return to Washington that no public servant in the history of the Republic had ever appeared to better advantage with his pants firmly caught in the crack of the door.There are differences, of course, between that day and this. I don't work for Mr. Kennedy - or if I do, it is from the private heart, not from public office. And as for the Library of Congress, it has long since grown accustomed to the alienation of hoped-for papers, some having been alienated as far west as Independence, Missouri. But whatever else is altered, the fact remains that a library, or the idea of a library, is here again in process of inauguration by a President of the United States and that I seem again to be part of the proceedings. If precedents still mean anything in this revolving world, the probability must be very great indeed that no good will come of it.No good, that is, to me. Amherst can be more hopeful and so too can this October valley and the old, soft, lovely hills off to the west of it where I have lived for half a biblical lifetime. The people of this countryside may forget in ordinary human course what anyone says on this occasion, but they will remember for many, many years that a young and gallant President of the United States, with the weight of history heavy upon his shoulders, somehow found time to come to our small corner of the world to talk of books and men and learning.I say "small corner" not in modesty but in Yankee modesty - which is a different thing. We may not be as conspicuous at this end of the Commonwealth, Mr. President, as some you must have heard of at the other, but we bear up. We remind ourselves that it was a citizen of this very town of Amherst who was described by a famous daughter as "too intrinsic for renown," and we like to think that even now, a century after Edward Dickinson's death, there are still men in these valley villages and up along the Deerfield, Bardwell's Ferry way and in the hills behind, who deserve the tribute of Emily's unfractured crystal of pure poetry, pure praise. But whether we are right or not - whether we and our neighbors are too intrinsic for renown or merely too remote for notoriety - we know an honor when we see one, and your presence here we take to be just that: an honor to this College and these counties and ourselves.Not to mention Robert Frost, for Frost, of course, is another matter - as he always was. There is an old Gaelic tale of the West Highlands called "The Brown Bear Of The Green Glen" which has a whiskey bottle in it so definitively full that not a drop can be added, and so fabulously copious that nothing is lost, no matter how you drink it. Frost's fame is like that bottle: it can't be added to because it is full already, and it won't draw down however it is drunk. We may name a library for him. We may go farther than that: we may give his name to the first general library ever to be called for a poet in America - which is what this library will be. We may pass even that superlative of honor: we may designate as his the first general library but one in the entire world to bear a poet's name - the one being the A. S. Pushkin State Public Library in farther Kazakhston in the U.S.S.R. We may do what we please. Nothing whatever will have happened to the bottle: it will merely continue to be full.This, I suggest, is a phenomenon which might well concern us on this particular occasion - the secret of that bottle. Is it the mere bulk and body of the fame which keeps it so miraculously brimming - the fact that no poet in English, with the single exception of Yeats himself, had as much fame in his lifetime as Frost had at the end of his? Is it the quantity of the reputation, the number of people who knew Frost's name or recognized him on the streets or crowded into those wonderful talkings which some called readings, and lined up afterward for autographs they rarely got?I doubt it and so do you. We know a little in our time and country about fame in bulk and its effect on lasting fame. At least we know what happens when a whole new industry is established, dedicated to nothing but the manufacture, in larger and larger quantities and in shorter and shorter periods of time, of cude, bulk reputation: we have seen its fruits. (Try not to see them!) If great actresses are in short supply, as they invariably are, two or three to a century being about all the natural processes can produce, the industry will assemble you a dozen assorted Greatest Actresses in a single season, inflate them with adjectives and launch them like blimps to float about for a year or three or maybe five or longer. But then what happens to them? Or to the greatest novels, the greatest plays, detergents, sedatives, cigarettes, laxatives, which circle with them?Or even to the greatest men? And even when they are great. For the industry processes everyone, true as well as false. Let the actual thing it self appear - Keats's seldom-appearing Socrates in fact and in the flesh - and the assembly line will multigraph him and pass him current by every mechanical means until nothing is left of the single, human fact of the man himself but his bubble reputation in as many million mouths as the new technology can activate. It takes an Einstein to survive it. And even Einstein had reason to be grateful for the isolation of his vast achievement out among the galaxies of space and mind where the copywriters couldn't follow.Yet Frost, too, survived, and with no such adventitious aid. Everything about him - the seeming simplicity of his poems, the silver beauty of his head, his age, his Yankee tongue, his love of talk, his ease upon a lecture platform - everything combined to put him within easy reach. No one in my time upon this planet was so pursued by fame as Frost - so "publicized" in the specific sense and meaning of that word. But even now, months after his death, the "public image," as the industry would call it, has already begun to change like the elms in autumn, leaving enormous branches black and clean against the sky.Frost too, it seems, but in a different way, an opposite way, is "too intrinsic for renown" - too intrinsic for renown to touch. Something in the fame resists the flame as burning maple logs - rock maple anyway - resist the blaze. And what it is, I think we know. At least there is an evening, not many years ago or many blocks from here - an evening others in this room remember - which might tell us. It was his eightieth birthday. Frost had been in New York where every possible honor, including some not possible, had been paid him, and, returning here to Amherst and his friends, he fell to talking of what honor really was, or would be: to leave behind him, as he put it, "a few poems it would be hard to get rid of."It sounds like a modest wish but Frost knew, as his friends knew, that it wasn't. Poems are not monuments - shapes of stone to stand and stand. Poems are speaking voices. And a poem that is hard to get rid of is a voice that is hard to get rid of. And a voice that is hard to get rid of is a man. What Frost wanted for himself in the midst of all that praise was what Keats had wanted for himself in the midst of no praise at all: to be among the English poets at his death - the poets of the English tongue.Which means something very different from being talked about or passed from mouth to mouth by reputation. Reputation - above all literary reputation - is a poor thing. It rises and falls. Consideration leads to reconsideration, fashions change and no one yet has heard the verdict of posterity because posterity has never come. Frost will be praised and then neglected and then praised again like all the others. It wasn't reputation he was thinking of that wintry evening: it was something else. To be among the English poets is to be - to go on being. Frost wanted to go on being. And he has.It is this fact - this actual and not at all imaginary or pretended fact - I wish to speak of for a moment: the persistence of this man. It has a certain relevance to what we do here. On the surface of these proceedings Frost's part in them is purely passive: nothing is asked of him but to receive the honor we now pay him and to relinquish a great name he does not own, having bequeathed it to the future - three syllables to be carved above a doorway... Frost and stone to age together. In fact, however, if one includes among his facts the fact I speak of, these roles are quite reversed: like the citizens of Colonus at the death of Oedipus in Sophocoles' great play, the passive part is ours. He gives: we take.Not that Frost was Oedipus precisely - except, perhaps, in his constant readiness to talk back to sphinxes. But there is something in the ending of that myth that gives this myth of ours its meaning. You remember how it goes - the wretched, unhappy, humbled, hurt old king, badgered and abused by fate, gulled by every trick the gods can play him, tangled in patricide and incest and in every guilt, snarled in a web of faithful falsehoods and affectionate deceptions and kind lies, exiled by his own proscription, blinded by his own hands, who, dying, has so great a gift to give that Thebes and Athens quarrel over which shall have him. You remember what the gift is too. "I am here," says Oedipus to Theseus, King of Athens, "to give you something, my own beaten self, no feast for the eyes..." And why is such a gift worth having? Because Oedipus is about to die. But why should death give value to a gift like that? Because of the place where death will meet him:

I shall disclose to you, O son of Aegeus,

What is appointed for your city and for you -

Something that time will never wear away.

Presently now without a hand to guide me

I shall lead you to the place where I must die.

And what is that place? The Furies' wood which no man dares to enter: the frightening grove sacred to those implacable pursuers, ministers of guilt, who have hounded him across the world.

These things are mysteries, not to be explained

But you will understand when you have come there.

The gift that Oedipus has to give is a great gift because that beaten suffering self, no feast for the eyes, faces the dark pursuers at the end.Frost, I said, was not Oedipus, and so he wasn't. But he too has that gift to give. And I can imagine some late student reading his poems in the library that bears his name and feeling, like Theseus, that the beaten and triumphant self has somehow, and mysteriously, been given him - a self not unlike the old Theban King's.Quarrelsome? Certainly - and not with men alone but gods. Tangled in misery? More than most men. But despairing? No. Defeated by the certainty of death? Never defeated. Frightened of the dreadful wood? Not frightened either. A rebellious, brave, magnificent, far-wandering, unbowed old man who made his finest music out of manhood and met the Furies on their own dark ground.We do not live, I know, in Athens. We live now in an insignificant, remote, small suburb of the universe. Reality, if one can speak still of reality, is out beyond us in the light-years somewhere, or farther inward than our eyes can see in the always redivisible divisibilities of matter that is only matter to eyes as dim and dull as ours.Homer's heroic world where men could face their destinies and die becomes to us, with our more comprehensive information, the absurd world of Sartre where men can only die. And yet, though all our facts are changed, nothing has been changed in fact: we still live lives. And lives still lead to death. And those who live a life that leads to death still need the gift that Oedipus gave Athens, the gift of self, of beaten self, of wandering, defeated, exiled self that can survive, endure, turn upon the dark pursuers, face its unintelligible destiny with blinded eyes and make a meaning of it ... self, above all else, without self-pity.

HONORARY DEGREE CITATION

JOHN FITZGERALD KENNEDYJohn Fitzgerald Kennedy - A citation for the president of the United States reads more like a prayer to the heavens, for all hopes for the sanity of national and international understanding depend upon you. But while pledging our support, we can applaud your skill, admire your courage, and be grateful for your leadership. By virtue of the authority vested in me by the Board of Trustees of Amherst College, I confer upon you the degree of Doctor of Laws.

HONORARY DEGREE CITATION

ARCHIBALD MACLEISH

Archibald MacLeish - Son of Yale, Harvard lawyer, American soldier and statesman, international poet and author. Through your efforts and through yourself you have revealed that incandescence which is the human spirit. Your interest has been deeper than morphology, for you have seen into the mechanisms of the mystery in a way to give hope to the myopic, and comfort to the blind. For going from man to men, from the particular to the universal in a way to enlarge understanding, we salute you. By virtue of the authority vested in my by the Board of Trustees of Amherst College, I confer upon you the degree of Doctor of Laws.

THE PRESIDENT'S REMARKS

AT THE LIBRARY GROUND BREAKINGMR. McCLOY, President Plimpton, members of the Trustees, Ladies and Gentlemen: I am privileged to join you as a classmate of Archibald MacLeish's and to participate here at Amherst, and to participate in this ceremony.I knew Mr. Frost quite late in his life, in really the last four or five years, and I was impressed, as I know all you were who knew him, by a good many qualities, but also by his toughness. He gives the lie, as a good many other poets have, to the fact that poets are rather sensitive creatures who live in the dark of the garret. He was very hard-boiled in his approach to life, and his desires for our country. He once said that America is the country you leave only when you want to go out and lick another country. He was not particularly belligerent in his relations, his human relations, but he felt very strongly that the United States should be a country of power and force, and use that power and force wisely. But he once said to me not to let the Harvard in me get to be too important. So we have followed that advice.Home, he once wrote, is a place where when you have to go there they have to take you in. And Amherst took him in. This was his home on and off for 22 years. The fact that he chose this College, this campus, when he could have gone anywhere and would have been warmly welcomed, is a tribute to you as much as it is to Mr. Frost. When he was among you, he once said, "I put my students on the operating table" and proceeded to take ideas they didn't know they had out of them. The great test of a college student's chances, he also wrote, is when he knows the sort of work for which he will neglect his studies.In 1937 he said of Amherst, "I have reason to think they like to have me here." And now you are going to have him here for many, many years. Professor Kittredge, at Harvard, once said that they could take down all the buildings of Harvard, and if they kept Widener Library, Harvard would still exist.Libraries are memories and in this library you will have the memory of an extraordinary American, but more than that, really, an extraordinary human being; and also you will have the future, and all the young men who come into this library will touch something of distinction in our national life, and, I hope, give something to it.I am proud to be associated with this great enterprise. Thank you.

Front page of The Amherst Student,

reporting the Kennedy visit

(click on image for full size view)