Archives & Special Collections Mary Bowles

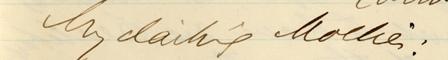

Skip to Main Content"My Darling Mollie": Mary Schermerhorn Bowles (1827-1893)

Mary Sanford Dwight Schermerhorn was born in 1827 to Henry Van Rensselaer Schermerhorn and Hannah Buckminster Dwight of Geneva, N.Y. Her father was a lawyer for nearly twenty years and then retired to run his farm. He and Hannah had three children, with Mary the oldest. When Hannah died in 1838, Mary went to live with relatives in Springfield, Massachusetts.1 There she attended the “Old High School” at 77 Maple Street in Springfield, where she met Samuel Bowles III. Mary and Sam were married at her father’s Geneva home in 1848 but returned to Springfield to live in the Bowles family home until 1852, when they moved into their own home on Union Street.

Mary Sanford Dwight Schermerhorn was born in 1827 to Henry Van Rensselaer Schermerhorn and Hannah Buckminster Dwight of Geneva, N.Y. Her father was a lawyer for nearly twenty years and then retired to run his farm. He and Hannah had three children, with Mary the oldest. When Hannah died in 1838, Mary went to live with relatives in Springfield, Massachusetts.1 There she attended the “Old High School” at 77 Maple Street in Springfield, where she met Samuel Bowles III. Mary and Sam were married at her father’s Geneva home in 1848 but returned to Springfield to live in the Bowles family home until 1852, when they moved into their own home on Union Street.

Published information about Mary Bowles comes to us primarily from letters to her from her husband as excerpted in George S. Merriam’s 1885 biography The Life and Times of Samuel Bowles, as well as through biographies of Emily Dickinson, where sources include Merriam’s book as well as letters from Dickinson to Mary; from Mary’s relative Maria Whitney to family members, and from husband Sam to friends Austin and Sue Dickinson.

Apart from Merriam’s favorable view, written while Mary was alive, the general consensus about Mary elsewhere is unflattering, and built upon a limited range of sources without full or examined context. On the whole, according to this view, she was not up to snuff in her capacity as the wife of "the most triumphant Face out of Paradise." The apparently more intellectual Maria Whitney and the sharp-witted Sue Dickinson, both of whom received some of Sam's intense letters, were more his kind of woman. People who regard Sam as a candidate for Emily Dickinson's "Master" also wonder at Sam’s choice of spouse.

It can't have been easy to be the wife of someone as determinedly sociable as Sam Bowles. Despite the fact that Mary was at least as well educated as her peers, there is good evidence to support the interpretation that she was also insecure and shy. Although in her own home she appears to have been a successful, warm hostess to an endless stream of visitors, out of her own realm she may have been awkward. In a letter to Austin Dickinson after an unsuccessful visit between the Dickinson and Bowles couples in 1861, Sam himself memorably likened Mary's "very timidity & want of self-reliance," to the habits of a porcupine: "The porcupine, I take it is really a very weak and [simplest] and distrustful animal, & so puts out his fretful quills to hide his soft heart."2

The soft-hearted if spiny Mary spent about 90 months of her life pregnant. Over 17 years she bore 10 children, including 3 stillbirths3 and 7 who grew to adulthood in her house. Surely such a large family would not have left Mary much time or energy to match Sam’s sociability, even if she inclined to it. Evidence of her frequent "sickness" (pregnancy, much of the time, as well as seasonal asthma or allergies) should be weighed against Sam's own well-documented chronic ill health (we know a lot about his bowels). They were well-matched in health concerns for the duration of their 30 years together.

A lengthy collection of letters often lulls us into thinking of them as a reliable record, when in fact they're selected (sometimes very selected) details. Despite the occasional husbandly grumbling to close friends about his wife's prickliness and ailments, it's hard to read Sam’s letters to Mary in the Bowles-Hoar Family Papers, or his comments about Mary to Judge Charles Allen (perhaps his best friend), and come away thinking that he would be satisfied to have posterity define his wife by a comment like the stinging one above, or even by his intense letters to other women and occasional suggestions of being tempted to infidelity. On the contrary, Sam’s letters to Mary are those of long, close association – they were comfortable together. If his surviving letters to her appear to lack evidence of sexual passion (although the number of children may speak louder than words), they nevertheless show how much the two depended on each other. George Merriam said that Sam "had a great command of the language of affection; his letters sometimes display a mastery of what Dr. John Brown calls 'that language of love which only women, and Shakespeare, and Luther, knew how to use.'"4 If Sam wrote one kind of letter to Maria Whitney -- sharing some particular angle of his wide-ranging personality -- and another to Sue, and another and another to Charles Allen and Austin Dickinson, then his letters to Mary are also characterized in a way special to her.

In return she gave him latitude. "Mrs. Bowles is very liberal in her government of me," he wrote Austin in a letter from 1859 in which he contemplated nipping off to see “your wife’s beautiful friend” (Kate Scott Turner).5 In fact, if Mary was occasionally jealous of her husband’s women friends (and we don't know that she was), on the whole she was remarkably generous about these relationships. We know she knew about them – his comments admiring women are everywhere in his letters to Austin and Charles Allen, and even in some to Mary. We know too that, among others, Maria Whitney and Sue Dickinson provided George Merriam with their letters from Sam. Evidently they didn’t regard them as something to be hidden from posterity, or Mary, who probably read them all.6

Mary's reputation as an unattractive, unsympathetic character is not helped by the fact that all published images of her show a dour-looking older woman. It’s the only way we’ve known her for more than a century. However, a 2011 addition to the Bowles-Hoar Family Papers contains an ambrotype of a woman we believe to be a young Mary Bowles, c. 1855-57, holding toddler daughter Sallie (Sarah Augusta), if the earlier date, or Mamie (Mary Dwight), if later. Mary’s plaintive, vulnerable little face looks out through glasses, but her daughter's contented pose suggests where the mother’s focus really lies.

The Bowles-Hoar Family Papers contain a small collection of letters from Mary Bowles to several of her children that reveal the depth of her dedication to them. They are entirely motherly, full of love and energetic kisses sent flying through an obliging postal service. Her children can never have doubted for a moment that they were everything to her.

Despite years of ill health, Sam's death in 1878 was a shock to everyone who knew him. Mary survived her husband by almost 16 years, mourning him deeply for the rest of her life. We sense the intensity of her loss through Emily Dickinson’s letters to her, some of Dickinson’s best, most beautiful “condolence" letters, to put it reductively. Dickinson understood what Mary felt – it is clear that Mary wrote and told her what Sam's loss meant – and Dickinson responded in her unique way.

A memorial pamphlet in the collection provides additional clues about Mary's personality. Testimony here suggests that she was more a partner to Sam Bowles than we have supposed, and a source of strength to their friends as well as family.

When all the letters in the collection between Sam and Mary are fully transcribed, we will have a more detailed picture of their relationship. Like most marriages, it will be a story of richer and poorer, and certainly sickness and health. Our view of Mary Bowles is also likely to be more interesting and nuanced than the one-note image of her that has prevailed up to now.

-M.R. Dakin

Notes

1. Mary’s maternal grandfather, James Scutt Dwight (1769-1822) owned a large, prosperous store in Springfield. He was succeeded in the business by his son George, with whom Mary probably lived. (See History of the Descendants of John Dwight of Dedham for Dwight genealogy.)

2. The unhappy visit that precipitated Sam's apology to Austin illustrates that the Dickinsons were more Sam's friends than Mary's, perhaps making for a struggle to find common ground. When one considers some of the likely dynamics among these four complicated personalities, it’s easy to imagine sparks flying. The "porcupine letter" is letter 6 from the Samuel Bowles Letters to Austin and Susan Dickinson, MS Am 1118.8. Houghton Library, Harvard University. Alfred and Nellie Habegger's invaluable work An Annotated Calendar of Samuel Bowles's Letters to Austin and Susan Dickinson (The Emily Dickinson Journal, November 2002, 11 (2), pg. 1-47) provides a synopsis and revised dates for these letters.

3. 1859 May 15, Sam wrote Austin about one of Mary's stillbirths: "I may find the sorrow qualified by the glad consciousness that my wife comes through the dark passage safely, - but to her, who has borne the heat & burden of the day, & all in gladness through the anticipated joy of maternity; whose life has been shared with his, & whose death leaves waste a wealth of sweet thoughts -- a fire behind & a blank before -- you may not imagine, I may not appreciate, all that tortures her soul. I do not pray your exemption from such risks: they are fearful, but even as failures, they have their uses. Greener grows the grass where the fire has burned." (Harvard, Bowles Letters, MS Am 1118.8, letter 1.) On the same day, Bowles also reported to Charles Allen: “It is the old disappointment. Mrs. B. was taken sick at 3 a.m. and at 8 p.m. relieved by instruments of a dead boy. It was a hard time, but not so bad as before. She is in a sad state, doubly prostrated by her physical suffering, and her great disappointment. It is easy for us to find consolation in such an hour; but for the mother, who has brooded for months over the expected babe, dreamed of it, fondled it and reared it, in imagination – for her to lose it just at the moment when its joy is needed to solace a trial men may never know; I take it that this we can faintly appreciate.” Letters to Charles Allen are in Box 2.

4. Merriam, George S., Life and Times of Samuel Bowles, New York: The Century Company, 1885, p. 209.

5. Harvard, Bowles Letters, MS Am 1118.8, letter 2.1.

6. To Mary: “Charles [Allen] got up a flirtation with a pretty Portland girl, and I contented myself with civilities to a married woman and an engaged one.” (July 27, 1861) Letters in the Bowles-Hoar Family Papers from Samuel Bowles IV (1851-1915) to Mary reveal that Mary actively participated in gathering materials for Merriam's book. She seems to have been taken aback when the book was published, as if she only later understood the extent of the invasion of her privacy. Her son assured her it was all for the best.