The Frederick S. Lane '36 Angling Collection

Clyde Fitch

The 1821 Collection

"Peter Parley" at Amherst

The Frederick S. Lane '36 Angling Collection

This article was published in the 1993-1994 edition of the Newsletter of the Friends of the Amherst College Library, since the publication of this article the entirety of the collection has come to Amherst College.

Mr. Frederick S. Lane '36 began his avocation of collecting fishing literature in the early fifties. What began as a simple manifestation of one man’s love of fishing and its literature has since become one of the most comprehensive collections of angling literature available, all within the confines of Special Collections of Amherst College. Mr. Lane has amassed upwards of 2200 volumes in his collection, approximately half of which have been given to Amherst. Taken as a whole the over 1100 books comprised by “The Frederick S. Lane ‘36 Angling Collection” constitute a multi-faceted specimen of the enormous genre of fishing literature. The undeniable diversity and breadth of this Amherst collection helps explain why fishing literature is generally acknowledged as the largest body of literature devoted to any single branch of sport.

The collection holds an appeal for the fisherman and naturalist alike. General subjects are covered in titles such as Samuel F. Hildebrand’s Cold-blooded Vertebrates, a book which includes not only fish in “Part I,” but also amphibians and reptiles in “Parts II and III”. Other books are not so much concerned with the creatures of nature as they are with human experiences in the outdoors. One such book, Thomas Anburey’s With Burgoyne from Quebec, recounts life in eighteenth century Quebec and the famous battle at Saratoga. Such books which explore the outdoors on a general level are sprinkled throughout the collection, but they do not compromise its predominantly “fishing” nature. In fact, it is the collection’s concentration of books on a very specific type of angling which distinguishes it from other collections of its kind.

That the backbone of the collection is composed of literature about fly fishing for trout and salmon reflects the fact that more has been written about fly fishing than any other method of taking fish. A perusal of the collection’s 148-page bibliography provides a clue to just how much has been written about this method of fishing. Short of reading all 1100 books in the collection, how could one fairly appraise their literary value? In my personal studies of fishing literature I discovered “The Angling Heritage,” an essay from Arnold Gingrich’s The Well-Tempered Angler. Gingrich describes the rich history of fishing literature in its nearly five centuries of existence. His essay serves as a map to help the green enthusiast of fishing literature find his way through the collection. Gingrich lists thirty books as a starting bibliography, classifying them according to his criteria of literary and instructional value. Of the thirty books listed, the Frederick S. Lane Angling Collection has seventeen of them, an impressive figure considering the vast numbers of fishing literature available:

CLASSIC

i. Dame Juliana Berners: A Treatyse of Fysshynge Wyth an Angle, 1496.

ii. Alfred Ronalds: The Fly-Fisher’s Entomology, 1836.

iii. Thomas Salter: The Angler’s Guide, 1814.

iv. W.C. Stewart: The Practical Angler, 1857.

v. Izaak Walton and Charles Cotton: The Compleat Angler, 1676.

VINTAGE

vi. Sir Humphrey Davy: Salmonia, or Days of Fly-Fishing, 1828.

vii. Francis Francis: A Book on Angling, 1867.

viii. Sir Edward Grey: Fly-Fishing, 1899.

ix. Frederic M. Halford: Dry-fly Fishing in Theory and Practice, 1889.

x. George M.L. LaBranche: The Dry Fly and Fast Water and The Salmon and the Dry Fly ,1914.

xi. G.E.M. Skues: The Way of a Trout With a Fly, 1921.

xii. Eric Taverner: Trout Fishing from all Angles, 1929.

MODERN

xiii. Ray Bergman: Trout, 1952.

xiv. Alvin R. Grove, Jr.: The Lure and Lore of Trout Fishing, 1951.

xv. John McDonald: The Origins of Angling, 1963.

xvi. Vincent C. Marinaro: A Modern Dry-Fly Code, 1950.

xvii. Lee Wulff: The Atlantic Salmon, 1958.

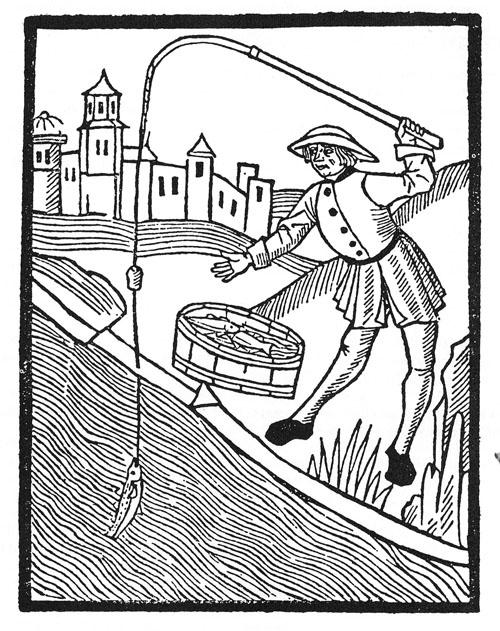

Although Izaak Walton may at once come to mind as the author of the first book on fishing written in English, he should be considered the father of fishing literature but certainly not the pioneer. The publication of A Treatyse of Fysshynge Wyth an Angle in 1496 accords Dame Juliana Berners with the distinction of the first to write about fishing in English.1 This contribution to the second Booke of St. Albans makes the abbess of St. Albans the matriarch of fishing literature and indebts all subsequent writers of it to her in some measure. The Lane Collection has two editions of this landmark work: the first American edition, edited by George W. Van Siclen (1875); and the more interesting of the two, a facsimile reproduction of the edition printed by Wynkyn De Worde at Westminster in 1496, edited by Reverend M.G. Watkins, M.A. (London: Elliot Stock, 1880).

The Treatyse secured its peak position in the ever-increasing pyramid of fishing literature by serving as a guide to merriment via fishing. At the outset Berners trumpets fishing as the cause for a merry spirit, for “... if the angler take fish, surely then is there no man merrier then he is in his spirit.” But gentle Dame Juliana does not stress actually catching fish as the only way to achieve a merry spirit, for if the fisherman “...fails of one (catching fish) he may not fail of another (achieving a merry spirit) if he doeth as this treatise teacheth....” Although she makes it clear that a man can find happiness along rivers without catching fish, this is first and foremost a fishing book. In its combination of simple philosophy with useful technique, the Treatyse serves as a blueprint for fishing literature: there is not one fishing book published even today that does not owe something in its techniques or style to the pen of Berners.

With all the novelty surrounding the Treatyse it is important to recognize that something like this had been done before in literature, but in hunting lore. Berners’s work was actually a fishing story written in the familiar tradition of the hunting treatises so prevalent in the Middle Ages. Hunting and falconry were chivalrous pastimes practiced by the nobleman. But at the time of the publication of the Treatyse, these chivalrous institutions had been celebrated to such an extent of overrefinement that a “new treatise” on hunting was oxymoronic— how could one add novelty to something rendered familiar by endless minor variations on the standard formula of the hunting story? Dame Juliana Berners provided an alternative. For the satiated hunting audience, her fishing story meant “...retirement in spirit far from the restless passion and triumphs of medieval hunting”.2

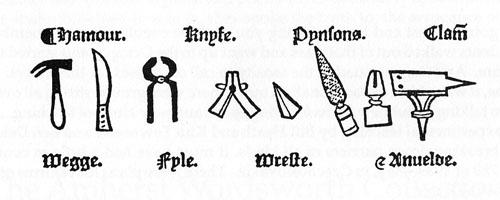

All of the illustrations are reproduced from Dame Juliana Berners, A Treatyse of Fysshynge wyth an Angle (London, 1880), a facsimile reproduction of the 1496 edition printed by Wynkyn de Worde.

Berners gave relief by providing a fishing story in the familiar outline of the hunting treatise. This traditional sporting treatise consists of two parts: the first is an argument and elevation of the subject, always followed by an instruction in technique, the second component of the treatise. In her commendation of fishing, Berners transforms the chivalrous energies of the hunter into the virtuous and quiet manners of the fisherman:

And therefore to all you that be virtuous, gentle and free-born I write and make this simple treatise following, by which ye may have the full craft of angling to disport you at your lust.

Berners also satisfies the second criterion of a sporting treatise, to serve the function of instruction, with overwhelming satisfaction. The comprehensiveness of her instruction remains unrivalled, for not only does she relate the baits and methods to catch eighteen different species of fish, but she also describes how to make the requisite fishing equipment.

In fact the most famous fishing story, Izaak Walton’s The Compleat Angler (1653), relied almost exclusively on the Treatyse as a source book. The influence of the nun and noblewoman of St. Albans is plainly evident in each of the eleven editions of The Compleat Angler in the Lane Collection. It is worthwhile to compare passages in Walton and Berners to demonstrate the fundamental impact Berners had on fishing literature, for one will see that the technical side of Walton’s story is essentially a more artful version of Berners’ pioneer effort. In describing how to color the fishing line Walton wrote:

And for dying your hairs, do it thus: Take a pint of strong ale, half a pound of soot, and a little quantity of the juice of Walnut-tree leaves, and an equal quantity of allum; put these together into a pot, pan, or pipkin, and boil them half an hour....3

Turning back one hundred and fifty-seven years to the Treatyse it is obvious where Walton learned the technique for coloring the hair line:

And to make a good green color on your hair, you must do thus. Take a quart of small ale and put it in a little pan, and add to it half a pound of alum, and put your hair in it, and let it boil softly half an hour....4

Although Walton varies little from Berners in line-coloring methods, it is in his description of the twelve artificial flies that he reveals his heavy reliance on the Treat yse. He begins his list of twelve artificial flies:

The first is the Dun-fly in March, the body is made of dun wool, the wings of the partridge’s feathers. The second is another Dun-fly, the body of black wool, and the wings made of the black-drake’s feathers, and of the feathers under his tail. The third is the Stone-fly in April, the body is made of black wool, make yellow under the wings, and under the tail, and so made with wings of the drake.

A look at the Treatyse shows the origin of the recipes and sequence of the flies mentioned by

Walton:

March: The Dun-Fly: The body of dun wool and the wings of the partridge. Another Dun-Fly: the body of black wool; the wings of the blackest drake; and the jay under the wing and under the tail. April: the Stone fly: the body of black wool, and yellow under the wing and under the tail; and the wings, of the drake.

The fact that Walton received such acclaim while using the Treatyse as a guide does not speak to his powers as a plagiarist; rather his borrowings from Berners highlight his inimitable ability to create a warm, idyllic story from something as mundane as fishing instruction.

Walton’s success with The Compleat Angler arose from his training as a writer, for he was a man of letters before a man of the angle. Born to a Staffordshire family of the yeoman class, Walton left for London in 1619 to follow his trade. It is generally believed that Sir Izaak was an ironmonger, a trade which gave him great fortune and enabled him to retire at the age of fifty so that he could, “Linger long days by Swaynham brook” in Stafford. As a writer Walton was a devout biographer, having published biographies of John Donne, George Herbert, and Richard Hooker, all churchmen and men of letters, and two of them great poets. Sometime after the death of his wife in 1662 Walton moved to Winchester, the area which brought him the acquaintance of the well-bred Charles Cotton. Walton found an immediate soul-mate in Cotton, for he also was a brother of the angle and a poet.

But Cotton was a fly fisherman, unlike the bait-dunking Walton. So in 1676 Walton asked Cotton to add a second part to The Compleat Angler dealing with fly fishing. Within ten days of this request, Cotton produced Instructions How to Angle for a Trout or Grayling in a Clear Stream, which was added to the famous fifth edition of The Compleat Angler in 1676. Cotton’s contribution has given the book more instructional value, a claim which is supported by the fact that virtually all subsequent editions have been published with this all-important second part. In the estimation of Arnold Gingrich, Walton “...gave angling not a how-to book of enduring utility, though even that could be said of Cotton’s part, but the greatest literary idyll that any language has ever bestowed on any sport.” It is, of course, the literary and idyllic quality of it that for centuries has recommended it to readers far beyond the community of fishing.

The enduring fame The Compleat Angler has achieved is best attested by the rate at which the book has been reproduced. In Walton’s lifetime the book saw five printings between 1653 and 1676, the famous fifth edition the first to include Cotton’s section on “fishing fine and far off”. Broken down by the centuries the book enjoyed five editions in the seventeenth, ten in the eighteenth, one hundred and sixty-four in the nineteenth and has been reissued at the astounding rate of two to three editions per year since 1935. Of the almost four hundred editions of the book, the Lane Collection contains a generous share of the most coveted. This assembly of editions reads like hall of fame desiderata for piscatorial bibliophiles: two editions edited by John Major, which saw fifty-six printings between 1823 and 1934; the Edward Jesse edition, reissued nine times from 1856 to 1903; two editions of the Marston, including the centennial edition; the Le Galienne edition, which was reissued six times between 1897 and 1931; and finally the James Russell edition, which is number two hundred seven out of a limited five hundred copies.5

By virtue of the numerous valuable editions of Walton’s classic, the Lane Collection could be adjudged superb. But the collection becomes even more formidable when one realizes that the assembly of The Compleat Angler editions composes only one segment of books considered to be classics in fishing literature. In the century and one-half between Berners’ milestone and Walton’s masterpiece, six books on angling were published in English, two of which can be found in the Lane Collection. The anonymously published The Arte of Angling (1577) was the next to succeed the Treatyse and distinguishes itself as the first writing on fishing in the form of prose dialogue. In assessing Walton’s sources for The Compleat Angler, it is important to recognize the influence of both Berners and The Arte of Angling: Walton’s classic is a combination of the Berners story line with the dialogue form and characters of the Arte.6 Walton’s genius was his ability to create a version of pastoral, complete with interspersed poems, from the story, characters, and dialogue that he found in Berners and the Arte. Among the six predecessors of Walton after Berners, John Dennys also put his stamp of originality on fishing literature and gave Walton cause for emulation. Dennys’ Secrets of Angling (first published in 1613, found in 1970 Freshet Press edition in the collection) is regarded as not only the first, but also the finest book of poetry ever dedicated to the subject of fishing. The literary affinity of fishing for poetry, and poetry for fishing, had thus been realized before Walton.

In addition to the holy trinity of angling authors Berners, Dennys, and Walton, many other books of high acclaim rest in the Lane Collection. In his An Anglers’s Rambles and Angling Songs (first printed in 1839, exists in 1923 J.B. Lippincott Company edition) Thomas Tod Stoddart (1810- 80) captured the art of fishing in verse as only Walton could do in prose. Andrew Lang’s prayer to Izaak Walton in his Letters to Dead Authors reveals in what class of poet-fisher Stoddart is regarded: “Father [Walton, if Master Stoddard [sic], the great fisher of Tweedside, be with thee, greet him for me, and thank him for those songs of his, and perchance he will troll thee a catch of our dear River.” W.C. Stewart’s Practical Angler (first published in 1857, here in 1883 Charles Black edition) deserves a place next to Stoddart, for his was the finest treatment of the fundamentals of trout fishing in clear water. The scope of its authority may be surmised by its smash-hit popularity—three editions were issued in the first year of publication,with six more printings surfacing between 1861 and 1893. Stewart had such great impact because he was the first proponent of upstream dry-fly fishing, a technique that has not changed today since its initial articulation in 1857.

Francis Francis (1822-86) picked up the torch of dry-fly fever ignited by Stewart with A Book on Angling (first published in 1867 but survives here in Longmans, Green, and Co. edition of 1885), in which the technique of upstream dry-fly fishing was elevated to the point of obsession. His staunch belief that “The angler should never fish downstream if he can by any possibility fish up” meant that there was no reason to fish otherwise, for if one can fish downstream very little prevents him from fishing upstream. The combination of Frederic M. Halford’s (1844-1914) Dry- fly Fishing: Theory and Practice (first issued in 1889, found here in 1973 edition) and Floating Flies (first issued in 1886, survives in collection in this first edition) pushed the dry-fly fishing craze to its apex in Victorian England. But Halford’s insistence on the floating fly was not confined to the British Isles, for it was his correspondence with Theodore Gordon, the American father of fly fishing, that introduced the technique to American waters.

The popular rationale behind the insistence on the dry-fly was that it served as the most exact imitation of the natural insect and was most likely to fool the fastidious trout. The impetus behind this movement for life-like imitation was started by Alfred Ronalds and his Fly-fisher’s Entomology (first issued in 1836 but survives here in second edition of 1839). The color drawings of the natural insect and their dressings for imitation by fly are regarded as the strongest factor for turning fishermen into a “race of angler-naturalists”.8 Lord Edward Grey (1862-1933), perhaps best known as England’s Foreign Secretary at the outbreak of World War I, also asserted his powers of preservation as a fly fisherman.

Three more books of the Lane Collection are essential reading for the beginning scholar of fishing literature: Charles Wetzel’s American Fishing Books (found here in the valuable first edition of 1950), Henry Bruns’ Angling Books of the Americas (also a first edition of 1975), and John McDonald’s The Origins of Angling (another first edition,1963). This triumvirate of bibliographers separates the extraordinary from the ordinary in fishing literature and helps bring the value of the works in the Lane Collection to its fullest expression.

Tyler S. Wick ‘92

ENDNOTES

1. The first known mention of fishing in English is found in The Colloquy on the Occupations, a late tenth-century book by Aelfric the Abbott. Fishing is only noted in an offhanded manner by the characters of the Colloquy: Magister: “What trade are you acquainted with?” Piscator: “I am a fisherman.” Magister: “What do you get by your trade?” Piscator: “Food, clothing and money.” (McDonald, John, The Origins of Angling, Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, 1963, pp 8-9).

2. Treatyse in McDonald, page 48.

3. Walton, Izaak and Charles Cotton, The Compleat Angler, Little, Brown, and Company, 1899, page 157.

4. Treatyse in McDonald, page 48.

5. Gingrich, Arnold, The Well-Tempered Angler, NAL Penguin Inc., 1987, page 226.

6. Although The Compleat Angler is generally forgiven for its lack of instructional originality, some recent editors have gone a step further and renewed their accusation of Walton as a plagiarist. This indictment arises from Carl Otto von Kienbusch’s discovery of the 1577 volume The Arte of Angling. This anonymously written book is a succession of exchanges between Piscator and Viator, the angling student of Piscator. Not coincidentally, the main characters of The Compleat Angler are called Piscator and Venator. Arnold Gingrich sees evidence of Walton’s acknowledgment of his debts of plot and character in his revisions of The Compleat Angler: “After the first edition, Walton changed his Viator to Venator and added a third character, Coridon”(Gingrich, 229).

7. Robb, James, Notable Angling Literature, Herbert Jenkins Limited,1947, page 105.

8. Gingrich, 245.

Clyde Fitch

This article was originally published in the 1983 Newsletter of the Friends of the Amherst College Library

Those who were at Amherst while Converse housed the library will remember an elegantly appointed, book-lined room on the second floor named for the alumnus whose books and furnishings were housed there: Clyde Fitch, Class of 1886. The contents of that room no longer form a single unit, but in Special Collections in the Robert Frost Library the Fitch collections remain a major focus of attention. Indeed, additions have been frequent over the past few years, with the active encouragement and support of Richard Fitch ‘32, who has enabled the library to acquire copies of typescripts of many of Fitch’s unpublished plays. And Professor Emeritus Ralph C. McGoun ‘27, in the course of several years of intensive work with the dramatic arts archives, has gathered together much additional material relating to Fitch’s undergraduate dramatic career, including many photographs.

Who was the man whose effects and memory remain the object of so much care and interest nearly 100 years after his graduation?

William Clyde Fitch was born in Elmira, N.Y., on May 2, 1865, shortly after Lee’s surrender, the son of a Union Army officer from Hartford and a Maryland belle. His birthplace was an accident of the war; most of his childhood was spent in Schenectady, N.Y. Before the age of 15, his creative and literary bent manifested itself in a short-lived, hand-produced newspaper, The Shooting Star, which survives today in the Amherst College collection, along with its rival, The Rising Sun, produced by his close friend Mollie Jackson.

Frail in health, Fitch spent much time away from home as a child. Eventually he prepared for Amherst at the Holderness School, which burned to the ground six months before his scheduled graduation. Despite that setback and, at the same time, a serious bout with typhoid fever, he entered Amherst as planned in 1882.

His attention to style and extravagance in dress brought “Billy” Fitch a good deal of unwelcome attention from his fellow students at first, but his intelligence, good humor, and obvious talents soon turned prejudice to admiration. He was active in dramatic productions from his sophomore year on, playing, among other roles, Constance Neville in She Stoops to Conquer, Lydia Languish in The Rivals, and Peggie Thrift in The Country Girl.

As a junior in Chi Psi, Clyde Fitch—who by this time had dropped the “William"—made his first foray into dramatic writing: when a one-act burlesque opera proved to be too short for the fraternity’s planned evening entertainment, Fitch wrote a second act. During this period he was also a frequent visitor to the New York theater, where he and a friend, Tod Galloway ‘85, once managed to see eleven productions within a single week.

After graduation and a summer in Newport, Fitch determined to make his way in New York. A brief period as a tutor to two young children is commemorated in Amherst’s collection by an elaborate handmade book, full of his typical wit, lively humorous illustrations, and clever turns of phrase. At the same time, Fitch became friendly with E.A. Dithmar, drama critic for the Times. After a heady summer of 1888 in England and Paris—where he read his first original one-act play, Frederick Lemaitre, to a small salon that included Bernard Berenson and the composer Massenet—he returned to an active social life in New York (becoming a member of the theater club, The Players) and an ever-increasing literary production (though at first without the success of publication).

The turning point in his life came with the opening on May 17, 1890, of Beau Brummell in the Madison Square Theater. Fitch had written the play as a commission for its star, Richard Mansfield; the production had a long and stormy history before its opening, and was stopped and restarted several times as financial troubles, differences with Mansfield over the script, and other problems arose and were settled. But the difficulties faded to nothing in the light of Beau Brummell’s brilliant success and a prodigious career was begun.

From then on, he always had at least one play in the works, writing anywhere, anytime an idea came to him (as well as more conventionally, by dint of hard work at his desk). His plays were the vehicles for many of the leading actors, and he generally—unlike most of his contemporaries—maintained complete control over the productions. He wrote original plays (more than 35), adaptations from European originals (more than 20), dramatizations of several novels (the best known, House of Mirth, was done in collaboration with Edith Wharton from her novel, and has been revived several times recently), vaudeville sketches, short stories, and one novel.

By the turn of the century, Clyde Fitch’s plays were setting box-office records. In 1901, he had four smash hits on Broadway simultaneously; 500 people were said to be earning their livelihood from the plays. But the critical reception in America, to his deep disappointment, was never much more than mixed, although Fitch was highly regarded abroad; indeed, he was the first American playwright to be accepted in Europe as a serious literary figure.

Fitch’s original plays dealt almost exclusively with American subjects, and ranged from light comedy (Captain links of the Horse Marines), through historical drama (Nathan Hale, Barbara Frietchie), western melodrama (The Cowboy and the Lady), and psychological drama (The Girl with the Green Eyes, The Truth), to tragic drama (The City). Characteristically, at the time of his sudden death in France on September 4, 1909, he had three plays in rehearsal; The City, which many consider his most powerful and mature work, opened three months later to great popular and acclaim, achieving 190 performances on Broadway before a successful tour.

Amherst’s collections today include not only all Fitch’s published works, but many manuscripts and typescripts of unpublished plays, some 30 in all, as well as letters and other manuscripts, and a substantial portion of his library (other parts of which are at The Players in New York). Though there is no separate room today devoted to Clyde Fitch, a number of the pieces that once graced the second floor of Converse now have pride of place in the Special Collections Reading Room, and others are available for special events, such as the candelabra and opera glasses recently lent to the Grolier Club for its exhibition, “Honour’d Relics.”

Clyde Fitch, though not as widely known today as he deserves to be, is a major figure in the history of the American theater. Amherst played a role in his early development and provided a setting for his theatrical beginnings, and we are proud to preserve his heritage.

-John Lancaster

The 1821 Collection

This article first appeared in the 1982 Newsletter of the Friends of the Amherst College Library.

Several years ago, Kurt Daniels ’23 conceived the idea of establishing a collection of books that would document publishing activity, and thereby also the intellectual, social, and literary climate, in the year of Amherst’s founding. Intrigued by the possibilities of the idea, we first assembled in one place what we already had in the Library, then consulted the very few bibliographies which afford a chronological approach, and finally, liberally supported by a fund established by Mr. Daniels, began approaching antiquarian dealers with our requests.

The dealers’ responses were in some ways the most entertaining part of the process. They ranged from utter bafflement as to why anyone would approach collecting from this chronological angle to wholehearted enthusiasm for this new slant on peddling their wares – an enthusiasm occasionally reflected in their prices!

In the three years of the 1821 fund’s existence, dozens of volumes have been added. Mention of a few may serve to give an idea of the range of the collection.

The first to be added was one Kurt Daniels himself found, a copy of William Cobbett’s Cottage Economy. In rapid succession followed a variety of literary, scientific, and political works: Byron’s Sardanapalus, the Two Foscari, and Cain, in one volume (London, John Murray); John MacCulloch’s A Geological Classification of Rocks (London, Longman), which fits well with Amherst’s strong 19th century geological holdings; Jean-Bapiste Say’s A Treatise on Political Economy (Boston, Wells and Lilly), the first American edition of this very influential work; and Foreign Slave Trade, a report to the directors of the African Institution (London), to name only a few.

Such works have formed the backbone of the growing collection, but it is the ephemeral, unusual, and offbeat items that have often provided the most enjoyment.

In the summer of 1821, Thomas Hornor took advantage of the scaffolding erected to repair the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London and built a hut at the very top, from which vantage point he drew careful views of the surrounding area (published in 1823 as four engravings). We acquired his prospectus, which contains an intricately folded plate delineating on a cutaway plan the route he took daily to the top of the dome.

From local dealers came three broadside printed forms of interest; two tax forms from Middle- town, Connecticut, listing some 40 items and categories of taxable property, with the percentage tax for each, and printed ship’s articles for a voyage of the schooner Tombolin of Newbursport, signed by all crew and the captain, Amos Dennis.

Most recently, through the good offices of Richard Linenthal ‘78, employed by Messrs. Quaritch of London, that firm presented us with three London newspapers from 1821, reporting the death of George III and the coronation of his successor, George IV. Quaritch was also responsible for enabling us to acquire the rare three-volume set describing Otto von Kotzebue’s voyage in search of a North-East Passage, illustrated with color plates, and including an account of a landing on the northern California coast. A copy of the German edition of this work had been one of Kurt Daniels’ earliest suggested possibilities for the collection; we are now glad we held out for the English.

And now a number of American almanacs for 1821 is a treasured find, still unbound as they originally appeared.

This fascinating collection leads us in an uncommon direction, a fine example of the sort of stimulus an interested Friend can offer to the growth of the Library.

-John Lancaster

“Peter Parley” at Amherst

This article first appeared in the 1982 Newsletter of the Friends of the Amherst College Library.

Samuel Griswold Goodrich was a prominent figure in the popular culture of the middle of the nineteenth century, chiefly because of the millions of volumes distributed under his pseudonym “Peter Parley” for the enlightenment and entertainment of young readers. These volumes, some of them ghost. written (one by Nathaniel Hawthorne), reached a wider audience than any other comparable series. They included both narratives (involving travel to foreign lands, used as a device to arouse interest in history and geography) and more overtly didactic works, often with questions at the foot of each page.

But Goodrich was also a politician and diplomat, as well as a literary publisher; his annual, The Token, included some of Hawthorne’s earliest pieces. He was a state legislator in Massachusetts, first in the lower house, then in the Senate, where he worked actively for various reform and educational causes during the 1840s. In 1851 he was appointed consul in Paris by President Millard Fillmore.

Until 1979, Amherst’s library, like any general library formed in the nineteenth century, contained a sampling of Goodrich’s productions. Now, thanks to the generosity of two donors, both connected to the College only at one remove, we boast one of the strongest collections anywhere of Goodrich material of all sorts.

Mrs. Harmon S. Boyd, whose late husband was a member of the Class of 1917, gave us the collection of Goodrich letters and documents which Mr. Boyd had acquired; his interest had been generated by living in close proximity to Goodrich’s Connecticut home. The collection includes letters from famous literary and political figures such as Victor Hugo, Alexis de Tocqueville, John Quincy Adams, official documents of Goodrich’s political career, and a number of his printed works.

Morris Cohen, father of Daniel Cohen ‘79, complemented the documentary and manuscript emphasis of this collection by his gift of more than 300 printed works. These include, of course, most of the ‘‘Peter Parley’’ titles (of which Mr. Cohen published a bibliographical list in 1977), but also works of other sorts: those for which Goodrich served only as publisher, such as the works of Hannah More, 1827; schoolbooks and other didactic literature written by Goodrich and issued under his own name; British imitations and piracies of the Parley books; and translations into other languages.

Mr. Cohen’s gift is remarkable both for the large number of volumes it contains, and for the state of their preservation. Books for children are notoriously difficult to collect. Despite relatively large print runs, few copies usually survive, and those that do are usually not in good condition for reasons familiar to most of us.

Children’s literature has also not been widely regarded as worth preserving, except for a few classics. But in recent decades social historians and investigators of popular culture have come increasingly to realize that such literature offers important insights into the nature of a society and the forces at work in its daily life. At the same time, historians of printing and publishing have stepped up their investigations into nineteenth-century trade activities, for which children’s literature provides particularly useful documentation.

The chief justification of special collections such as the Goodrich in an undergraduate college library must be their use by students who learn from working with them, and by scholars who transmit their findings through publication. The Goodrich collection is already used in Amherst College courses, and has also attracted scholarly visitors from elsewhere. As it becomes known and grows its usefulness will increase.

-John Lancaster