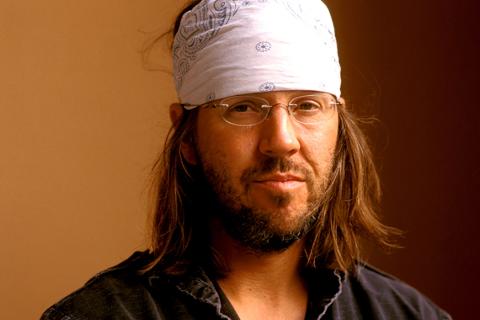

Archives & Special Collections David Foster Wallace at Amherst College

Skip to Main Content

David Foster Wallace’s time at Amherst College is the story of a brilliant young mind searching for identity and voice while struggling with debilitating depression. Wallace arrived at Amherst in the fall of 1980 when he roomed in a suite in Stearns. He made a strong impression on many of his professors, such as Willem DeVries who recalled, “I don’t want to say he was scary but he made me work harder than any other student I ever had.”

Wallace focused on his studies and received excellent grades throughout his time at Amherst. He won the Borden Freshman Prize in his first year, followed by the Armstrong Prize in English and the Hamilton Prize in Economics. He also found a group of friends, among them Mark Costello with whom he shared a room in Moore during his sophomore year. Wallace returned home for winter break at the end of the fall semester 1981, and took the spring 1982 semester off because of his depression.

Wallace returned to Amherst in fall 1982, again rooming with Costello, this time in Stone, one of the Social Dorms that were demolished to make room for the new Science Center. That fall, Wallace, Costello, and other friends revived an old Amherst student publication and launched Sabrina as an outlet for their humorous observations on college life. (The original Sabrina ran from 1950-1962.) One of Wallace’s contributions to the first issue in November 1982 was a parody of a Hardy Boys mystery titled “The Sabrina Brothers in the Case of the Hanged Hamster.” It is a short piece with dark humor around suicide and sexual assault; in spite of the “To be continued...” at the end, it never was. Sabrina appeared regularly throughout the 1980s, then sporadically into the early 1990s.

During his summer at home in 1983, Wallace was first prescribed the antidepressant Tofranil. Shortly after returning to campus for the fall 1983 semester – what would have been his senior year – he once again withdrew from school and returned home. He continued to read voraciously while away from Amherst, immersing himself in the fiction of Thomas Pynchon and Don Delillo and the philosophy of Wittgenstein. It was also during this time that he produced his first short story published in a more serious college magazine: “The Planet Trillaphon as it Stands in Relation to the Bad Thing” in the 1984 issue of The Amherst Review. The story opens:

“I’ve been on antidepressants for, what, about a year now, and I suppose I feel as if I’m pretty qualified to tell what they’re like. They’re fine, really, but they’re fine in the same way that say, living on another planet that was warm and comfortable and had food and fresh water would be fine: it would be fine, but it wouldn’t be good old Earth, obviously. I haven’t been on Earth now for almost a year, because I wasn’t doing very well on Earth. I’ve been doing somewhat better here where I am now, on the planet Trillaphon, which I suppose is good news for everyone involved.” (26)

Wallace took a creative writing course during the spring 1984 semester from visiting professor and novelist Alan Lelchuk. He received an A-, the lowest grade he had earned since his freshman year. Undeterred, Wallace returned to school in fall 1984 more enthusiastic about fiction than ever. His friend Mark Costello graduated in spring 1984 having completed two theses: one a study of the New Deal, the other a novel. Wallace was determined to match Costello’s accomplishments and began work on two theses of his own. He worked with advisor Willem de Vries on a philosophy thesis, Richard Taylor’s “Fatalism” and the Semantics of Physical Modality, and with English professor Dale Petersen on a novel, The Broom of the System.

After graduation, Wallace moved to Tucson to pursue an MFA in creative writing at the University of Arizona. The Broom of the System was published by Viking Penguin, Inc. in 1987, appearing simultaneously in hardcover and paperback. That year, he also served as a visiting instructor at Amherst. In 1999, the college awarded him an honorary doctor of letters degree.

Remembering David Foster Wallace

Wallace died Sept. 12, 2008, when, after a decades-long struggle with depression, he hanged himself at his home in Claremont, Calif. He was 44.

In the essays below, four people who knew Wallace at Amherst—his English thesis adviser, two friends and one former student—remember a young man who wrote his papers late at night when he couldn’t sleep, who played Bruce Springsteen’s “I'm Goin' Down” until the tape broke and who, even in college, possessed a “Dickensian genius for spawning new characters and newly devised connections among them.”

Members of the Amherst community may post their own remembrances here.

David Foster Wallace Collections

In March 2010, the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin announced that they had purchased Wallace’s personal papers – including his personal library -- and would make them available to researchers:

- David Foster Wallace: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center

- David Foster Wallace: Harry Ransom Center Digital Collections

In December 2012, Columbia University Press published Wallace’s second Amherst thesis, Fate, Time and Language: An Essay on Free Will.

The Archives & Special Collections at Amherst holds a small number of letters Wallace wrote to Professor William Kennick; the copies of his senior theses he submitted as a student in 1985; and a complete set of his published works, including several pre-publication proofs and variant editions.

Brief Interview with a Five Draft Man

In 1999, Amherst magazine ran a feature-length Q&A interview with David Foster Wallace.