Archives & Special Collections Patterson's Riddle

Skip to Main ContentRebecca Patterson's The Riddle of Emily Dickinson

"My friends are my 'estate.' Forgive me then the avarice to hoard them! They tell me those were poor early, have different views of gold. I don't know how that is." (Emily Dickinson to Samuel Bowles, c. August, 1858, AC ED646a) [1]

"My own feeling (tentative like everything about ED at present writing) is that she had many enthusiasms, couldn't live without them, and went from one to another, perhaps even two at once, but for different reasons." (Richard Sewall to Jay Leyda regarding the candidates for "Master," July 29, 1960.)

Any attempt to understand the context of the circa 1859 daguerreotype thought by some to show Emily Dickinson and Kate Turner will soon lead to consideration of The Riddle of Emily Dickinson (1951), a biography of the two women by Rebecca Patterson.

Patterson’s Riddle was half biography of Dickinson and half biography of Mrs. Turner; the link between the sections was the relationship between the two women. Patterson emphasized the importance of Turner to Dickinson, a contention most people familiar with Dickinson’s life will accept, although the depth and duration of the relationship are still debated. Patterson herself believed the women were in love with each other and that Turner's termination of the relationship caused lasting grief to both. Might Patterson's book shed light on the daguerreotype said to show the two women?

Catherine Mary Scott Turner was Sue Gilbert Dickinson's friend from their time together (c. 1849-1850) in the Utica Female Seminary to Sue’s death in 1914. Kate and Emily met in 1859, the former then a young widow, her husband, Campbell Ladd Turner, having died of tuberculosis in 1857. As far as we know, the women saw each other only a few times, in January 1859, October 1861, and January 1863. [2] Turner's last visit to Amherst in Dickinson's lifetime was in 1877, at which time Dickinson refused to see her (on a similar visit in 1873, old friend Abby Wood Bliss had insisted that Dickinson appear, and the poet relented). To Dickinson, Turner could be numbered among the many friends – Sophia Holland, Jane Humphrey, Harriet Merrill, Abiah Root, and Abby Wood, to name a handful – who entered her life and then were too suddenly gone, some out into the wider world and some "sleeping the churchyard sleep." [3] Dickinson's friends were important to her, and each one that dropped away was a deeply felt loss. The sentiment behind Dickinson's lament to Turner -- "Why did you enter, sister, since you must depart?" was one she had voiced before. [4]

In writing Riddle, Patterson had access to material from Turner’s family that other biographers had not seen. Two of Turner’s grand-nieces, Margaret Synnott Johnston and Katherine Anthon Wood (daughters of Turner’s niece Edith Scott Johnston), still had in their possession Turner’s letters to her family, as well as her diaries. The material must have been voluminous, because what survives of it – three volumes of travel diaries – shows that while she was abroad Turner wrote regularly to her friends and family in New York and elsewhere, often numbering the letters in order to keep track of when one was sent and whether it arrived. She also regularly noted her incoming mail.

When Patterson first approached Turner's family, they were very willing to let her take the material away and copy it. This she did, keeping the precious copies in a briefcase set aside for the purpose (the briefcase is now long gone). However, when Turner's family learned the nature of Patterson's theory of the relationship between their aunt and Dickinson, they rescinded permission to use the material. For this reason, Patterson was unable to include photographs, to quote from correspondence in the family's possession, or to fully document her work. Most (but not quite all) of the original material and the copies were subsequently destroyed.

Patterson was still able to assemble information from her notes and thereby document Turner’s life from birth to death. The diaries and correspondence from Turner to family members enabled Patterson to be thorough, particularly about the last third of Turner's life, including her attachment to a daughter figure she called “Florence Eliot,” a pseudonym for an English girl whose real name was Florence Dicken Statham.

Patterson was still able to assemble information from her notes and thereby document Turner’s life from birth to death. The diaries and correspondence from Turner to family members enabled Patterson to be thorough, particularly about the last third of Turner's life, including her attachment to a daughter figure she called “Florence Eliot,” a pseudonym for an English girl whose real name was Florence Dicken Statham.

Over the course of her research, Patterson developed a deep affection for Turner that comes through clearly in her book and is documented in letters to fellow biographer Millicent Todd Bingham (daughter of Mabel Loomis Todd, the poet's editor) and to Florence Statham's daughter Irene Grasemann (see pdf). Her affection may have grown in proportion to the hostility her theory and subsequent book provoked among Dickinson scholars, some of which is documented in her correspondence to Bingham. By the time her book was published, Patterson even claimed (somewhat defensively) to have more interest in Turner than in Dickinson.

In 2010, while looking into the history of Dickinson and Turner, as well as of Riddle itself, the Archives and Special Collections corresponded with the family of Rebecca Patterson, which led to the acquisition of what remained in the Patterson family library of books relating to Emily Dickinson. The books are some of the standard volumes one would expect from a scholar who wrote a biography of Emily Dickinson and taught her poetry for many years. Although well used, they contain few annotations, and Patterson’s daughter, Anne, confirmed that her mother was not in the habit of writing in her books except to sign her name.

In 2010, while looking into the history of Dickinson and Turner, as well as of Riddle itself, the Archives and Special Collections corresponded with the family of Rebecca Patterson, which led to the acquisition of what remained in the Patterson family library of books relating to Emily Dickinson. The books are some of the standard volumes one would expect from a scholar who wrote a biography of Emily Dickinson and taught her poetry for many years. Although well used, they contain few annotations, and Patterson’s daughter, Anne, confirmed that her mother was not in the habit of writing in her books except to sign her name.

However, one of the books contained (slipped in) several photographs relating to Riddle, specifically those of Kate Scott Turner that Patterson described but did not include in her book.

The earliest known photograph of Kate Scott Turner

The earliest known photograph of Kate Scott Turner

"Distinctly sweet your face stands in its phantom niche"

(Emily Dickinson to Kate Turner, c. 1860, AC Tr60b)

"I stopped with conviction at the portrait of a young girl with dark hair, beautiful dark eyes, full mouth and strong chin. On the back of this photograph was Mrs. Anthon's name."

(Riddle, p. ix. This image is from Rebecca Patterson's 5"x 7" photograph copied from the Scott-Johnston family's copy, itself probably a carte-de-visite or cabinet card (more likely the latter) taken from an original daguerreotype c. 1852-56. Patterson provided this image to Richard Sewall, who used it in his "Life of Emily Dickinson.")

The Scott home in Cooperstown, NY, c. 1949

"Crowded as the house is, on the north by the churchyard and on the east by River Street, the most attractive part of the grounds has always been the expanse of lawn and garden, with its margin of stately trees, at the corner of Elk and River Streets. During the summers of Kate's girlhood it was almost a mass of flowers."

(Riddle, p. 40. Photograph by Rebecca Patterson. The people seated near the house are probably Margaret Johnston and Katherine Anthon Wood, Kate's grand-nieces.)

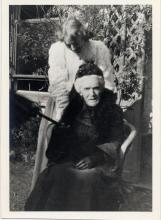

Kate Turner at 60

"Now she was sixty, and her hair was completely white. The beautiful dark eyes, however, shone as brightly as of old, and the ivory skin was clear and not so deeply lined as might have been expected. Although life had dealt cruelly with Kate Anthon, she was still a very attractive woman. As always, she was dressed in deep black, perhaps in the handsome black dress, with the fine lace at throat and shoulders, in which she was photographed a few weeks later."

(Riddle, p. 19. See also p. 360, where Patterson records that this photograph was taken on October 30, 1891. Image from Patterson's copy of the photograph, probably from an original in the Scott-Johnston family.)

Kate Turner and Katherine Graham Bramley in Grasmere

"There is one last picture of Kate Anthon. She is sitting in the garden of her friend Frank Bramley... She likes to visit his house and watch him paint. Now he is taking her picture, and she shakes her umbrella at him. Not easily pleased with a photograph, she has been known to tear up snapshots of herself... This lover of the South and of sunlight is strongly defended against a northern summer. As usual, she is dressed in complete black -- trim black coat, long black kid gloves, and small black cap like a crown on her white hair."

(Riddle, p. 372. Image from Rebecca Patterson's copy, probably provided to her by Mary Margaret Kirkby, a friend of Kate's from Grasmere. Patterson visited Grasmere and spoke with Kirkby during her research.)

These artifacts – the photographs above, the Grasemann letters and a memoir by Florence Statham (the memoir is described in Riddle; see pdf) – are a sample of the material that may be used to understand Patterson's book and further document the lives of both Rebecca Patterson and Kate Turner. Material at other institutions includes:

Kate's travel diaries from the 1870s: With the cooperation of the New York State Historical Association (NYSHA), we were able to borrow and then photocopy Turner's diaries. Researchers may read them in the Archives and Special Collections, but copies must be obtained through the Association. The diaries document Turner's life during the illness of her second husband, John Hone Anthon (he died in 1874 from what Patterson suggests was a brain tumor), and then during her sister's losing battle with tuberculosis in 1875-76. Emily Dickinson does not appear at all in these journals, and Sue Dickinson is only mentioned a few times in connection with letters sent or received. The journals provide insight into Turner's personality and document the difficulties of her life in this period. Patterson was also able to consult a diary from 1881, which has since disappeared.

The Martha Dickinson Bianchi Papers, [ca. 1834-1980], a collection at Brown University, contains the late letters (c. 1904-1917) from Kate Turner to Sue Dickinson and her daughter, Martha Dickinson Bianchi. There are few references to Emily Dickinson in these letters (one dated 1914 is quoted in Bianchi's biography Emily Dickinson Face to Face), but Patterson drew on these letters heavily for details of Turner's last years.

Riveting letters between Patterson and Millicent Todd Bingham may be found at Yale in the Millicent Todd Bingham Papers (MS 496D). Their extensive correspondence (most of it from Patterson to Bingham) reveals the evolution of Patterson's theory and provides biographical detail for Patterson herself.

Harvard University's collection MS Am 2380 (Ward, Theodora Van Wagenen, b. 1890. Notes and correspondence concerning Emily Dickinson) contains correspondence between Patterson and Theodora Ward, author of Emily Dickinson's Letters to Dr. and Mrs. Josiah Gilbert Holland (1951), Capsule of the Mind: Chapters in the Life of Emily Dickinson (1961), and Associate Editor (with Thomas H. Johnson, Editor) of The Letters of Emily Dickinson (1958). The material in this collection provides additional documentation of the atmosphere in which Patterson wrote her book. It also includes many letters to Theodora Ward from William H. McCarthy, the representative of the Rosenbach Company, the firm that handled the sale of the Dickinson manuscripts to Harvard for Alfred and Mary Hampson. Patterson's theory inspired McCarthy to write Ward, "If it were not for you, I should bitterly remark, ‘Why do women try to write books?’” [5]

All the material relating to Patterson’s research may be of help in reading and substantiating Riddle; however, none of it provided any information directly relevant to the "new" daguerreotype that sparked the research into Patterson's book. In fact, Patterson herself noted to Bingham that in all of Turner's material, Dickinson was only mentioned twice: "I should tell you, of course, that in this vast mass of material Emily Dickinson is mentioned only two times, and then in surprisingly cold terms." [6]

Statistically, it's a safe bet that Kate Turner thought of Emily Dickinson from time to time during the course of her long life. However, one couldn't prove it by the documentation that Patterson possessed and that still exists, or by referring to Turner's correspondence to family members that once existed and that Patterson alluded to in her book. Although the Riddle of Emily Dickinson provides useful biographical information about both women, and insight into Dickinson's poetry, it doesn't document this daguerreotype of two women. [7] In order to do that, one would need to find more information about the period in which Dickinson and Turner saw each other, 1859-1863.

What we see in the daguerreotype, then, is the captured essence of two lives that intersected here, forever memorializing a friendship. Perhaps future scholarship will determine whether there is more to tell about its history.

-M. R. Dakin

September, 2012

Notes:

[1] Letter from Richard Sewall to Jay Leyda, July 29, 1960. Jay and Si-lan Chen Leyda Papers, TAM.083, Box 8, Folder 8. Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, Elmer Holmes Bobst Library,

New York University Libraries.

[2] Dates of Turner's visits: In his My Wars are Laid Away in Books (New York: Random House, 2001, pp. 373 and 708), Alfred Habegger consulted the letters of Samuel Bowles to Sue and Austin Dickinson to arrive at these dates. Habegger also found and used Turner's diaries hiding in plain sight for many years at NYSHA.

[3] Emily Dickinson to Abiah Root, 1850. Lettter 39 in Thomas H. Johnson's Letters of Emily Dickinson, Belknap Press, Harvard, 1958.

[4] Emily Dickinson to Kate Turner, c. summer 1860, transcript by Kate Turner Anthon, Amherst College ms TR 60b, Thomas Johnson letter 222.

[5] William H. McCarthy to Theodora Ward, January 9, [1950], MS Am 2380 (Ward, Theodora Van Wagenen, b. 1890. Notes and correspondence concerning Emily Dickinson), Box 2, Folder 2). Houghton Library, Harvard University.

[6] Rebecca Patterson to Millicent Todd Bingham, April 7, 1948. Yale University, Millicent Todd Bingham Papers (MS 496D) Box 84, Folder 253.

[7] Rebecca Patterson also wrote Emily Dickinson's Imagery (University of Massachusetts Press, 1979), a well-regarded study of the poet’s symbolism.