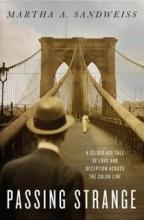

Passing Strange by Marni Sandweiss

|

A Gilded Age Tale of Love and Deception Across the Color LineBy Professor of American Studies and History Martha A. Sandweiss (Penguin).

Reviewed by Robert E. Weir

Hiding in plain sight

“Miscegenation is the hope of the white race.” These words were uttered in 1885 by Clarence King, a renowned figure in his day. As a celebrated mountaineer, geologist, explorer, raconteur and author, King moved in the highest circles of New York City society, dined at the White House and counted among his intimate friends such luminaries as historian Henry Adams, novelist Bret Harte, Secretary of State John Hay, painter John LaFarge and architect Frederick Law Olmstead. His associates attributed King’s unorthodox racial views to his natural exuberance and pensive mind. None suspected that, in 1888, King would match deed to words by marrying an African-American. Nor did they realize that, for 13 years, he lived a double life. In New York’s exclusive clubs, he was white gentleman Clarence King; across the Hudson River, in Brooklyn, he passed as James Todd, a “colored” Pullman porter, the dutiful husband of former slave Ada Copeland and the father of her five children.

Martha Sandweiss (who, after many years at Amherst, will soon take a new position at Princeton) recounts the strange and wondrous tale of King and Copeland with the flair of a mystery writer and the discipline of a skilled historian who knows that not all riddles resolve themselves neatly. Hers is a tale “about love and longing” but also about “desire and duty,” built upon “secrets crafted to protect and to hurt; silences created by neglect and with intent.” King’s life as a public person is easily reassembled from the sort of archival records historians routinely consult; for his life as a white man passing for black, the narrative thread is as slender as that of his wife, a woman born into a nation that did not value her humanity enough to record even rudimentary details. By necessity, the story Sandweiss tells of Mr. and Mrs. “James Todd” is an imaginative reconstruction.

But it is far from idle speculation. Sandweiss peels away the gilding of late Victorian society to explain how King’s deception was possible. It was a time in which the American frontier King explored as a youth was closing, eugenics passed as hard science, whites went “slumming” in black clubs for exotic thrills, fortunes were made and lost and restrictive social norms induced neurasthenia. Yet, as Sandweiss reminds, the “late-nineteenth-century American city offered a stage for social reinvention.” The very anonymity of New York made it possible for the Todds to “hide in plain sight.” So too did prevailing views of race. King had only to cross the Brooklyn Bridge to be white, and becoming black required only his word. That King was light-complexioned, fair-haired and blue-eyed was of no consequence in an era in which having only one African-American great-great-grandparent made one a “Negro.” Victorians feared blacks trying to pass as white, but they could not even imagine the reverse. Sandweiss draws parallels between King and female impersonator Earl Lind, a contemporary, though Sandweiss’s stronger comparison is to NAACP cofounder Walter White, a man of African-American ancestry who appeared to be Caucasian.

This is a love story, but it’s also a tale of deceit, financial ruin, prolonged melancholia and moral ambiguity. Sandweiss details the psychological and financial strain that King’s double life imposed on him. It was easy to convince white neighbors that he was black, but to play that role among African-Americans, King had to be a social and cultural illusionist. His wife, apparently, knew nothing of his deception until a 1901 deathbed letter revealed it. Nor was she aware that King had bankrolled the deception through reckless borrowing—much of it from John Hay—or that Hay was the mysterious benefactor whose monthly checks sustained her family for the next 30 years as she battled for access to an alleged trust fund. Ada lived until 1964. What must she have thought as she witnessed some members of her family become “white” and several remain “black,” while the civil rights movement called race privilege into question?

This is one of many unanswered questions. We do not know if King felt like a black man trapped in a white man’s body or if he was a colonizer reveling in his wife’s exotic Otherness. Was King a tragic figure hemmed in by social norms or a blackface minstrel whose mask allowed him to slum to his heart’s content while retaining white privilege? What went on in Ada’s mind as she was drawn into a relationship marked by frequent pregnancy and prolonged absences of her spouse?

We cannot answer these queries with certainty, but we can learn that race in America is often a fiction that its citizens choose to see or not to see. With material this rich, there is no need for didactics or sermons, and Sandweiss wisely allows her compelling narrative to induce contemplation. This book is destined for awards, and it will deserve every one of them.

Weir is a visiting professor of history at UMass and a freelance writer.