The Experiment

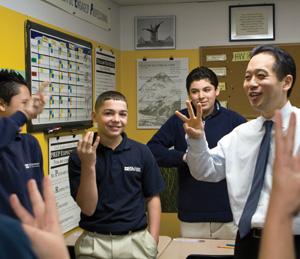

"It's very easy, when kids come from challenging circumstances, to want to make excuses for them, but it's a slippery slope," says Yutaka Tamura '94, at right, founder of Excel Academy.

|

By Katie Bacon '93

In July 2003, Yutaka Tamura ’94 stopped by a two-story vacant bank in a strip mall in East Boston. Planes from nearby Logan Airport went roaring by every minute or so, only a few hundred feet away. Tamura had recently won state approval to open a new charter school, Excel Academy, and had signed up 100 sixth graders to enroll for the fall. But he was still waiting for the lease on the vacant bank to come through. It seemed an unlikely setting for a school, but he could make it work—and it was pretty much the only option he had.

Tamura’s goal was to start a school for underserved students in an urban location—a school that would address the achievement gap between students in wealthy, primarily white suburbs and those in low-income, primarily minority urban neighborhoods. “That gap was, and still is, one of the biggest civil rights issues of our era,” Tamura says. East Boston, a neighborhood with many Latino immigrants and a growing population of lower-income families, fit his criteria: about 1,000 children attended its one public middle school, and their averaged scores on the MCAS—the standardized test taken by all public school students in Massachusetts—were among the lowest in the state.

Just three years before, Tamura had been a businessman, poised to enter Harvard Business School. In the summer of 2000, he’d paid his deposit and even seen his dorm room. But something didn’t feel right. “I knew I wanted to leverage my business experience and do something kid-related. That was my angle to get into business school, but it was also what I wanted to do.” Tamura had worked with kids before, both as a counselor at a camp in Vermont and as part of an Amherst class on urban education, for which he’d tutored kids in the Holyoke public schools.

Instead of starting at Harvard, Tamura took a low-paying job teaching history—his major in college—at a private school in the wealthy Boston suburb of Weston as a way to get more experience before starting something of his own. In 2002, he was accepted into a highly selective fellowship program called Building Excellent Schools (BES), which guides people through the process of founding charter schools in underserved locations. He put together a founding group, including East Boston community leaders and two Amherst classmates: Seth Reynolds ’94, a management consultant who had served with Teach for America, and Owen Stearns ’94, a strategy consultant to foundations who had run an after-school program in Boston. (Both Reynolds and Stearns now serve on Excel’s board, with Stearns as its chair.)

In February 2003, the Massachusetts Department of Education approved Excel’s charter. Tamura chose to open the school that fall, and within a week, he was recruiting on the streets of East Boston and nearby Chelsea, handing out flyers outside schools, dropping off materials at beauty salons and setting up information tables at community events. He met with parents, hired a staff and, during the two months before school opened, worked feverishly to transform the vacant bank into a school.

Sixth-grade science class with teacher Katie Lewkowicz

|

Excel now serves 209 fifth through eighth graders—69 percent of them Latino and 75 percent from low-income families. Recognized as one of the best charter schools in the state, and in the country, it has found success where few others have. Its students consistently rank at the top of the charts on the MCAS. Last year, on the English portion of the test, Excel’s seventh graders beat out 460 other public and charter schools to be first in the state. The school is doing well by other measures, too, including its low rate of student attrition and the top college-prep schools that its graduates attend.

Many organizations become inextricably identified with their founder. Excel Academy exists because of Tamura, but it’s become larger than him. Not the type to sit still, Tamura resigned as executive director in 2008 and, in January, took a new job that will help him to reach many more students. Yet Excel is not only surviving but thriving.

But the success didn’t come easily. Excel’s first year was smooth, but when the school added a grade and doubled in size the following year, things started to unravel. The school was built on the strength of its teachers; it had no consistent, overarching policy on how to handle behavior problems. That fall, students started drawing graffiti in the bathrooms, wandering the halls during class, fighting on the school bus. Teachers were spending much of their time on discipline issues. “We knew we wanted to serve these kids, but in retrospect, the vision for how to do that wasn’t clear,” Tamura says. The students, not the adults, were controlling the culture.

Excel’s solid first year of test scores was soon undermined by the chaos enveloping the school. Results in math dropped by about 20 percentage points that second year. “Everyone walked into the school with a pit in their stomach, because we never knew what to expect,” Tamura says. Becca Moskowitz, the only teacher from that year who remains at the school, agrees. “The kids weren’t behaving well, because we weren’t asking them to,” she says. “One of the teachers referred to it as a sinking ship, and it pretty much was.”

The charter school movement is one outgrowth of “A Nation at Risk,” a 1981 report commissioned by the U.S. Department of Education that warned of “a rising tide of mediocrity” within the public school system that threatened “our very future as a nation and as a people.” Charter schools are part of the public school system in that they receive public funding for each child they educate, but they are independent in almost all other ways: They are free to design their own missions, curricula and spending plans. Because their teachers are generally not in unions, charter schools are exempt from district structures for salary and tenure, and this gives charters much more freedom over hiring and firing. Students who apply to charter schools are selected by a lottery process. Once enrolled, they are regularly tested to make sure they meet state standards; if students fall behind, their schools face losing their charters.

The first charter school opened in Minnesota in 1992; now, more than 3,500 exist in 40 states. Critics argue that they undermine public school systems by whisking away the best students and parents. Even though charter schools can’t pick and choose which students they take, there’s a compelling element of self-selection, since students and parents must seek out and apply to the schools. Some critics also believe that special-needs students are generally served less well by charters than by regular public schools and that test scores of some charters are skewed upward as a result of having fewer of these students. Charters are also criticized for shifting funds away from district schools.

Proponents argue that students need educational options and that by providing an alternative, charter schools can push public schools to improve. Tamura is firmly on the side that views it as imperative to offer choice to low-income students. “If you’re from a different socio-economic background you have options: parochial school, private school,” he says. “Low-income families don’t have that choice, and at a fundamental level, all we want to do is present an alternative.”

A so-called "no excuses" school, Excel holds students to high academic and behavioral expectations. These schools are highly regimented--some say too regimented--and they're increasingly the model of choice for urban charter schools.

|

Charter schools vary widely in their educational philosophies. Some focus on a particular area, say science or the arts. Some emphasize community involvement or creative thinking. Excel is part of a growing, informal network of what are often called “no excuses” schools. Some of them, like Excel, are stand-alone charter schools; others are part of non-profit organizations like the Knowledge is Power Program (KIPP), Achievement First and Uncommon Schools. All “no excuses” schools require some combination of extended school days and school years, tutoring programs on Saturdays and extra classes in English and math. They test students and evaluate teachers frequently. Finally, they focus on character education through a set of strict rules—from sitting up straight in class to finishing homework down to the last punctuation mark.

In the context of these schools, the phrase “no excuses” means two interrelated things: first, that for these students, failure is not an option, and second, that they will be held to high academic and behavioral expectations, no matter their circumstances. “It’s very easy, when kids come from challenging circumstances, to want to make excuses for them, but it’s a slippery slope,” Tamura says. “Kids from urban, lower-income situations have more uncertainty in their lives. They like certainty, and one way of creating that is with a lot of structure.” These schools are highly regimented—some say too regimented. But in many cases, their students are achieving impressive results. And increasingly, “no excuses” is the model of choice for urban charter schools.

|

With the school slipping away from them that second year, Tamura and Owen Stearns brought in a consultant whose suggestions ranged from greeting students at the door to creating strict school-wide academic and behavioral expectations. Over Christmas break the principal left, and Tamura and Stearns worked to implement the new plans. “After a culture is in place, it’s very hard to turn it around. So we had a real sense of urgency,” Stearns says. Graffiti was erased, holes in the wall fixed. Excel Academy was on its way to becoming a place where a student who rolled his eyes at a teacher went to detention that afternoon, no exceptions, and where a student who neglected to do her homework—no matter the reason—stayed late until she finished it.

Still, it was a difficult spring. Tamura was serving as both principal and executive director, working 14-hour days. “I thought it wasn’t out of the question that I would get fired,” he says. The teachers hadn’t been hired to work at such a regimented place, and many didn’t agree with Excel’s new philosophy. At the end of the school year, 80 percent of the staff chose to leave. Many of the students, too, reacted against the stricter atmosphere. Twenty-eight of 194 students transferred out before the end of the year.

By the next fall, Excel had a new principal and a mostly new staff. Tamura, the principal and others retooled the school’s curriculum, behavior plan and day-to-day operations, setting everything down in three giant binders. “Because we were operating very consistently, the kids felt much more comfortable at the school,” Tamura says.

Komal Bhasin, Excel's principal, greets students and checks their uniforms at the start of the day.

|

These days, Ann Waterman Roy, who replaced Tamura as executive director, goes outside at 7:30 every morning to greet each student with a smile and a firm handshake. The students pass inside for a uniform check with the school’s principal, Komal Bhasin. “Could I check your belt?” Bhasin asked one student on the day I visited in January. “Take off your hood,” she said to another. “Could I see the logo on your sweatpants?” She sent one girl off to the side—the pompoms on her boots were against the rules. The school requires any student out of uniform to sit in the dean’s office until a parent can bring in the proper item of clothing. The uniform check is part of the school’s policy of “sweating the small stuff,” Bhasin says. “The kids know they can’t do anything drastic: I freaked out over their belt, so what am I going to do if they do anything else?”

Two days after Barack Obama’s inauguration, during the eighth grade’s weekly community meeting, Bhasin gave a quiz based on the ceremony. “At what time on Inauguration Day did Obama officially become president?” she asked. While a small group of students was conferring, the rest started to snap their fingers—Excel’s form of supportive encouragement. One student answered quietly, “Twelve p.m.?”

“Use your high-school interview voice,” Bhasin replied, before encouraging the class to cheer the correct answer. Bhasin then played a clip from Obama’s speech: “For we know that our patchwork heritage is a strength, not a weakness.” When the clip ended she said, “Let’s do a posture check.” All the students sat up straight in their chairs. “Now,” the principal asked, “what’s the difference between a patchwork and a melting pot?”

The backbone of Excel’s behavior plan is an elaborate merit/demerit system. It rewards good behavior with privileges—points to spend at the school store, for example, or passes to use the back stairway. Students who collect a certain number of demerits face a variety of consequences, from after-school study halls to exclusion from school events to in-class suspension, during which they attend school but may not interact with their peers. A weekly report tells each student his or her merit/demerit score and allows the staff to examine larger trends: Why is one homeroom having more trouble than the others with discipline issues? What sort of discipline problems crop up before vacations?

One common criticism of “no excuses” schools is that their strict structure and emphasis on shaping behavior is a paternalistic effort to replace the culture in which the kids grew up. As the education historian Diane Ravitch wrote in a Sept. 16, 2008, blog post on the Education Week Web site, “Do poor black and Hispanic kids really need to be in ‘no excuses’ schools that insist on rote learning and rote behavior? That take control of their lives and change their culture? Should this be the model for education for children of color in big cities?”

Rebecca Wilusz ’93 directs the Upper School at Prospect Hill Academy in Somerville, Mass., which also serves a low-income demographic but does not share Excel’s “no excuses” approach. From working with several Excel graduates who’ve gone on to Prospect Hill’s high school, Wilusz has a positive impression of Excel. Yet when it comes to “no excuses” schools in general, she shares some of Ravitch’s concerns. “There’s a real tension around creating good education for urban children of color,” Wilusz says. “Sometimes I feel like the ‘no excuses’ model would never fly with white students in suburban districts, and it worries me that we would use a model for one group and not another.”

Another criticism is that “no excuses” schools, with their intense focus on academic achievement, high test scores and playing by the rules, discourage some of the neediest students from signing up or push them to leave if they don’t fit the mold. This gets at a thorny question: Should charter schools be all things to all students? Excel is probably not the perfect fit for all students, yet it does a good job of keeping those who walk in its door. Of last year’s fifth, sixth and seventh graders, all but two returned for the current school year.

When you talk to Excel students or graduates, most mention the strictness, and some talk about feeling distanced from their own culture. Yet they all see the school as a place that has opened doors. Juan Ochoa, a sixth grader born in Colombia, used to get straight C’s, but at Excel he’s on the honor roll. “Before, I didn’t want to go to school,” Ochoa says. “I didn’t want to wake up in the morning. This school is strict, but in a good way. They push you to your full potential.” John Tesoriero, a Venezuelan immigrant, was in Excel’s first graduating class and is now a junior at St. John’s Prep outside Boston. In retrospect, Tesoriero strains a bit against the strict culture at Excel—its requirement of professional handshakes as greetings, its limiting of the time students can spend socializing outside the classroom. He feels, he says, that the rules took away from his childhood. But the trade-off was worth it to him. He has a list of 20 colleges, including Amherst, that he’s considering applying to. “Now that I look back, I think Excel and the teachers helped shape who I am,” he says. “If I hadn’t gone there, I probably wouldn’t be at St. John’s, and I wouldn’t be considering the colleges I am.”

Teacher Caitlin Moore leads a "fishbowl" discussion in her seventh-grade social studies classroom.

|

Bhasin, Excel’s principal, views the culture of compliance as a jumping off point for creative teaching in the classroom. On the day I visited, a seventh-grade social studies class was having a “fishbowl” discussion. The teacher, Caitlin Moore, set out the questions for the day: “Is civilization a good thing? Which lifestyle is better: hunting and gathering or farming?” The class was set up in two circles: the students in the inner circle discussed a question; the students in the outer circle observed and gave feedback; then the groups switched places. At the end came a musical-chairs-style free-for-all in which students switched into the inner circle when they wanted to add a point to the discussion. In a school where class sizes run in the mid- to high twenties, the fishbowl is a way to bring all the students into the conversation.

Moore started out by tossing a basketball into the middle of the inner circle. The students passed it around crisply. “This is what it should feel like today. You’re focused, you’re quick, you’re looking for who’s open,” Moore said. The students started talking over the first question. “Civilization is better because there are more jobs,” one student said.” “I disagree. Civilization allows some people to become more powerful than others,” another replied. A third student jumped in: “Without civilization we wouldn’t have problems like racism.” The conversation continued, with quick points and counterpoints. Moore turned to the outer circle and asked for feedback. “Outside circle, I want to hear shout outs,” she said. One student called out, “Speak louder.” Another said, “Don’t be afraid to shoot because you might miss the basket.”

A few weeks after my visit, Emily Glasgow ’98 observed a similar fishbowl discussion. The principal of a public school in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Boston, Glasgow brought a team of teachers to Excel for the day. “We’ve been pushing ourselves to improve our performance data, and I was trying to say to them [that] there are some schools with populations like ours that have been having success with these kids.” Glasgow has an interesting perspective: she was Excel’s dean of students during its difficult second year. At that time, she says, the school “felt like structures were being imposed just for the sake of those structures.” These days, the school seems different to Glasgow. “I was excited to see this very tangible energy and passion and love for learning. It felt stable and happy.”

Excel measures itself by its students’ academic success: their MCAS scores and the high schools (and, eventually, colleges) they attend. Many Excel students go on to college-prep or magnet schools in the Boston area, including Phillips Academy Andover and Boston Latin. This year, as Excel’s first graduating class starts its college search, the school has organized college visits and workshops on everything from financial aid to the application process. “My expectation is that 90 percent will apply to college,” Tamura says. “I really want to see how it all turns out.”

After six years working flat-out at Excel, Tamura wanted something new, somewhere else. The political climate in Massachusetts had some bearing on his decision. For the past several years, the number of charter schools in Massachusetts has been bumping up against a cap set by the state. As a result, several prominent charter school founders have left, many of them for New York City, where Mayor Michael Bloomberg and schools chancellor Joel Klein have been aggressively pushing the expansion of charter school networks.

|

“In most industries, the best people want opportunities for growth, advancement and expansion, and it’s been harder for that to happen in Massachusetts,” Tamura says. That climate may be changing. In January, a few weeks after the release of a study by the Boston Foundation finding that Massachusetts charter schools generally produce significantly better results than public schools, Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick proposed lifting the cap. Not long after that, President Obama made a national call for states to lift their caps on charter schools. Patrick’s proposal is now making its way through the state legislature, but its success is by no means a given. Stephen Mugford ’89 is one of those eager to see the cap lifted. The head of strategy at Capital One bank, he joined Excel’s board two years ago. “If we wanted to replicate Excel, it would be really hard to do with the current cap situation,” he says. “We’re still a little bit of an island, which is great if you’re on the island. But if you look at the need out there, it’s a shame we can’t do more of these things, because they really work.”

In January, after moving to New York, Tamura became chief operating officer of Teacher U—a joint venture by the charter school networks KIPP, Achievement First and Uncommon Schools, in partnership with Hunter College, to create a program that trains people to teach at “no excuses” schools. His move reflects the reality he saw at Excel: he’d review 2,000 résumés each year to find the five to 10 hires he believed were the right fit. If the “no excuses” movement is going to grow beyond the roughly 150 schools that now exist, there needs to be a bigger pool of trained people to draw from. At Excel, teachers have been taking kids from districts that score around the 10th percentile on the MCAS and bringing them up to the very top of the ranks, essentially erasing the achievement gap. Tamura believes that needs to happen more—not just in a scattering of charter schools, but in our education system as a whole.

![]() View more photos of Excel Academy by Samuel Masinter '04.

View more photos of Excel Academy by Samuel Masinter '04.

![]() Hear audio from a lecture by David Whitman '78, author of Sweating the Small Stuff: Inner-City Schools and the New Paternalism. Whitman spoke in Pruyne Lecture Hall on April 24, 2009.

Hear audio from a lecture by David Whitman '78, author of Sweating the Small Stuff: Inner-City Schools and the New Paternalism. Whitman spoke in Pruyne Lecture Hall on April 24, 2009.

Katie Bacon ’93 is a writer and editor based in Boston. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Harvard Law Bulletin and other publications.

Photos by Samuel Masinter '04